I was struck with the beginnings of the idea for my project during the first few weeks of class.

In Mark Hansen’s essay on New Media, he describes how computational media can do two things: it can better exteriorize and disseminate an individual person’s experiences for the consumption of others, or it can “mediate for human experience the non- (or proto-) phenomenological, fine-scale temporal computational processes that increasingly make up the infrastructure conditioning all experiences in our world today.” He goes on to describe how this second form of mediation makes people aware of “transcendental technicity,” meaning human beings are made privy to the inner workings of the digital world and the vast amounts of data and knowledge it contains than was previously possible.

I am a fan of baseball and I have been since I was a young child, so I immediately drew a connection between these statements to the explosion of baseball data that is now available to the public online. Websites like Baseball-Reference, FanGraphs, and Baseball Savant have given anyone who desires it access to massive stores of data from the past and present regarding baseball games and the players who play in them.

I am a user of these sites and I am trying to understand statistics more, but this topic appealed to me for another reason in relation to this class. As we went through more reading material and explored different definitions of critical making, I continued to think more and more about the negative repercussions that over-reliance or over-consumption of statistical professional sports information can have on a person. As I have detailed in my previous blog posts, constant attempts to compare, rank, discredit, or pare down the people who play professional sports to their statistical representations can lead people to forget that athletes are people who have troubles, make mistakes, and deal with things every other regular person does. They aren’t just paper dolls to be played around with, regardless of their paycheck or job description. While these attitudes are also built up by and influenced by a number of other factors, such as the current state of popular sports media and social media and general, extreme levels of access to statistics can exacerbate these attitudes.

As I pondered how I would address this topic in a project using MAX/MSP, I first wanted to address some boundaries on a particular type of clip or era of baseball history I would explore. This exploration eventually lead me to focus my project on the “steroid era” of Major League Baseball, which lasted from approximately the late 80s to the late 00s and is labeled as such due to widespread usage of Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs) with no punishment despite nominal rules in place restricting or banning these substances.

Focusing on this point in the sport’s history ended up allowing me to expand my thoughts on the critical aspects of my project in connection to our class discussions.

Initially, I focused on this era due to the extreme statistical accomplishments of some of the players suspected of/proven to be users of PEDs, as well as the fact that this was the most recent peak in the sport’s national cultural relevance. Many notable players from this time period, including Barry Bonds, Rodger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa were also made hot topics again in the baseball/sports media worlds, as they were recently up for election into the National Baseball Hall of Fame for the last time and all ended up not being elected, mostly due to voters’ objections to their presumed steroid usage.

However, as I dug deeper, I began to notice deeper ideas that could become present in my project if I focused on this time period, the first being the line between the past and the present in regards to technology. Baseball-reference was founded in 2000, so much later than the start of the steroid era, and was therefore not publically accessible yet.

Thinking about this tension of past versus present in relation to my thoughts on baseball stats made me think about how both the steroid era and the present are dealing with a kind of depleted archive of information. In the past, there were incomplete or nonexistent statistical archives of baseball events from the field of play. While this project focuses on critiquing the overuse of statistical information to analyze real people, I do appreciate what its availability has done to promote interest in or passion for the game, so I can understand why work was done to fill these knowledge gaps.

In the present, there is a lack of archival information and representation of what was going on off the field, or to contribute to the results on the field. Again, sports cannot exist in a vacuum and there are so many ways that the people playing them can affect and be affected by extraneous factors, like easy access or pressure from competitors to use to PEDs. These kinds of things are not well represented on sites like baseball-reference. One of the most interesting, dramatic, or even human aspects of sports is also the fact that a lot of it comes down to judgment calls, whether that be on the part of the officials or the players. This means that the desire to quantify every little play and interaction and then viewing the archival record of said interactions as the gospel truth can be problematic.

Furthermore, all of this got me thinking about themes of authenticity versus unauthenticity. How important is authenticity in sports? If you are just watching for “entertainment,” for a spark of adrenaline when “your” team scores, what does it matter to you what is going on behind the scenes? Is it destructive or harmful to one’s emotional state to find catharsis in performance moments where the performers are breaking the rules or are manipulating said performance in their favor? How does money plan into this? How does entitlement on the part of the fan play into this?

Overall, baseball in today’s world is a sport of archives. While the contents of said archive are much different than the archives discussed by Saidiya Hartman in the essay Venus in Two Acts, I was struck by a few of her points regarding archival information and its relevance to my project’s points of interest.

“How can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know?” How can a number embody a life’s work? How can a single number or a series of numbers or a grid of numbers respect what we cannot know? How can a thirty-second video clip encapsulate one’s whole life’s work in the minds of a thousand others?

She goes on to say that “history pledges to be faithful to the limits of fact, evidence, and archive, even as those dead certainties are produced by terror.” Just like the archive in her essay, I don’t have the whole story in front of me looking at a set of tables and charts, and thinking that I do or spinning tales to my own liking around what I have in front of me would not be helpful. I strove to address all of these points within my project.

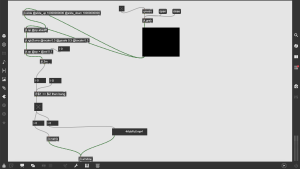

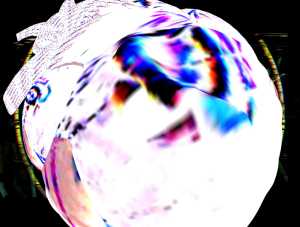

My project consists of clips of the most prominent players from the steroid era collected from MLB’s Youtube channel with statistics from baseball-reference overlaid on top of them. The visual and audio content of each clip slowly fades in over the course of the video, forcing the viewer to only engage with the statistics before the rest of the content emerges. Each statistic cycles through on top of the video as it plays. The statistics are representative of the featured player’s total statistical achievements from the year of the selected clip and they are displayed to the viewer in the same font as they are displayed on baseball-reference’s website.

Clips and their matching sets of statistics are cycled through at random from my library. Interspersed with these are edited versions of the title card of This Week in Baseball, which is also what the title of my piece is based on. This Week in Baseball was a compilation show that used to air on ESPN highlighting some of the most interesting MLB moments during the past week. In these edited title cards, I overlaid the show’s logo with either quotes from pieces of sports media centering around MLB players who played during the steroid era, particularly Barry Bonds, or pieces of freeform writing where I tried to channel different voices that I imagined to be those whose knowledge and use of sports analytics exceed that of what I find of be useful or comfortable.

Using these edited title cards, my project almost appears to be a long-running, freeform episode of the show. In addition to presenting my project on an older television, this further emphasized the dissonance between the past and the present in terms of sports analytics understanding and debate.

My project is aimed toward baseball fans, both casual and more intense, as well as those with a general interest in media and U.S. pop culture history. It may be confusing to those unfamiliar with statistics used in baseball as well as the cultural context surrounding the steroid era and its biggest names, but my main goal with it is to make those familiar with the topic rethink their assumptions about it.

My goal for the final presentation of my project shifted a lot over time. At one point, I had an idea of making it an interactive display where viewers would have to select a clip to watch, almost like a Youtube page. This would put the onus of consuming the visual and analytical information about each player on the viewer, just like how it usually is in real life, as most people who heavily engage with statistical sports information do so as a hobby. While this appealed to me, I thought presenting my work on the older TV would centralize the tension between past and present in a more compelling way than that would. I wanted to make very clear how the steroid era is in the past, and viewers can only view them through an altered, mathematical, archival lense from the present.

I also considered implementing footage of sports commentary shows like those on ESPN and pictures of articles or Twitter threads centering around the exact discussions and comparisons about players that I wanted to highlight. I decided against this to make the viewer more directly confront the source material and have their own thoughts about it rather than accept the opinion of someone else. While commentary shows and other media like that are important in shifting sports discourse, I wanted this project to be about each individual’s respective experience with sports viewership and its relationship to analytics.

Multiple projects we discussed in class inspired me to make my project. “Every Shot, Every Episode” by Jennifer and Kevin McCoy was one of the first things we saw in class that really caught my attention, as I liked the way it organized and parceled up information into more understandable, archival packages.“A Recipe for Disaster” by Carolyn Lazard served as perfect visual inspiration for what I wanted to do and evoked similar themes of disruption of an accepted audiovisual media.

When I was considering implementing materials from ESPN broadcasts or Twitter threads, I think that would have turned this project into more of a “postinternet” piece than it is now. Trying to parse the meaning of “postinternet” from Conner’s article was one of the most interesting pieces of the critical making puzzle for me, as I wondered throughout this course if someone in the present needs to have a complex, meta-view of the internet and its communities to make astute commentary on the topic or if they can still do so from within internet systems and structures of thinking. While I am still not sure of the answer to that question, I do not think I really got close to breaking through this barrier as the presentation of my project and its contents were for the most part pretty straightforward archival footage processing.

In sum, my project was an exercise in critical making for myself. To me, the part of the concept of critical making that stood out to me was that it is not only a process by which someone produces a critically engaged work, the creator themselves has to be critically engaged with the content such that they gain a new perspective on their subject through the production of the work.

I can say this certainly happened for me. As I worked through this project, I thought a lot about how I have utilized sports analytics in the past and how I hope to be more intentional about them in the future. I actually write for the sports section of the Duke Chronicle, so I think it is especially important for me not to fall into the trap of viewing the world of sports through the lens of numbers in boxes and nothing else.

Also, I realized throughout this project that I was projecting a lot of judgment onto those that I feel need to do a better job respecting athletes and what they do. This projection of judgment onto others rather than only the systems of social media and online discourse that almost force those interested in sports who want to participate in online communities around them to be combative and overzealous in making comparisons was something that I need to think over more as I move on from this project.

I think there is a lot of room for exploration in different directions with my project, as well as many technical aspects that could be improved upon. While I chose to go in a different direction, I think the point I was trying to make with my project would be more clear and more effective if I had ended up choosing to include either sports media or some kind of expectation-shaking element. Technically, I think the text could have been implemented in a more aesthetically fitting way and that the project would be greatly improved with text-to-speech functionality. I regret that I didn’t manage my time better and ask for more help during the semester so that my project could be better, but I hope that it will be of interest to you in class anyway.

Here is a link to a folder with some documentation.