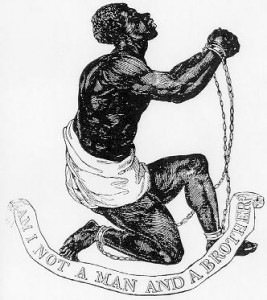

In this endlessly interconnected internet age, the idea that an image can have a profound and widespread impact hardly needs to be explained; it’s implicit. The advent of both photography– the way in which potent images of current events could be quickly and realistically produced– and the internet–the way in which they could be widely and rapidly disseminated–hastened and increased the importance of this phenomenon of images used to provoke political discussion. And an image can in fact be worth a thousand words; in cases from India’s struggle for independence, to the 1960’s civil rights movement, to the war in Syria today, images of social injustice and war have been able to provoke if not a direct solution, the conversation that brought that solution about. But while modern technology expedited the rise of disseminated images provoking social change, it was not solely responsible; this phenomenon was able to take place before the camera was invented, before the internet was invented. It took place, for instance, in 1787, with the engraving by Josiah Wedgewood of a kneeling, chained and supplicant slave, with the powerful words below: “Am I not a friend and a brother?”

(http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5e/BLAKE10.JPG)

This image didn’t come out of the blue; it was made for specifically for the purpose of moving hearts and minds. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787 by Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson. While the founders themselves were Anglican, the movement was popular amongst Quakers, who made up the other 9 founding members; these were William Dillwyn, John Barton, George Harrison, Samuel Hoare Jr., Joseph Hooper, John Lloyd, Joseph Woods, James Phillips and Richard Phillip, and later Josiah Wedgwood. Clarkson had campaigned for the movement previously and became the first historian for Britain’s abolition movement; Wedgewood was the 13th son of Thomas Wedgewood and a political reformer involved with the Unitarian Church.

Just a quick glance at the image reveals how pathos-evoking it must have been at the time. The figure is strong, vital, well-muscled; yet his circumstances have bent him in two, forcing him to beg for the basic rights that should be his due. His wrists are shackled to his ankles; it’s unlikely he’s able to stand up to full height. Even were he not in this unnatural position of supplication, he would not be able to stand as an autonomous agent should be able to do. His facial expression is nearly blank, numbed; but his lips are parted, as if to enunciate the words at the bottom of the image. Like Shylock asking “if you prick us, do we not bleed?” the caption states baldly that what in the distorted current structure of society should be a rhetorical question, is a genuine question because of how warped standards had become. “Am I not a man and a brother?” Is he? Whether or not a black man is human is of course a rhetorical question to the modern reader– but whether it was rhetorical or not would be less evident for the 19th century reader, and would force reflection. The question became the catchphrase of the British and American abolition movements, and the image was widely reproduced. Men purchased snuffboxes with the image; ladies wore bracelets and hairpins. According to David Dabydeen for BBC History, the image became “the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th century art.” In Joseph Hothschild’s book “Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery,” the author argues that “Wedgewood’s kneeling African, the equivalent of the label buttons we wear for electoral campaigns, was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause.” This particular image wasn’t just harrowing and politically effective; it was landmark.

Sidiya Hartman notes in her book “Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route” that the image is perhaps more insidious than it may at first seem. While it is clear that the figure is on bended knee, she argues that he is less begging God for freedom than the people of Britain, France and America, which, to the modern ancestor of slaves, is far more demoralizing. To ask God for your freedom is one thing; to ask fellow humans is quite another. The man in the image is begging for freedom, and the image itself begs those who see it to open their minds and hearts.

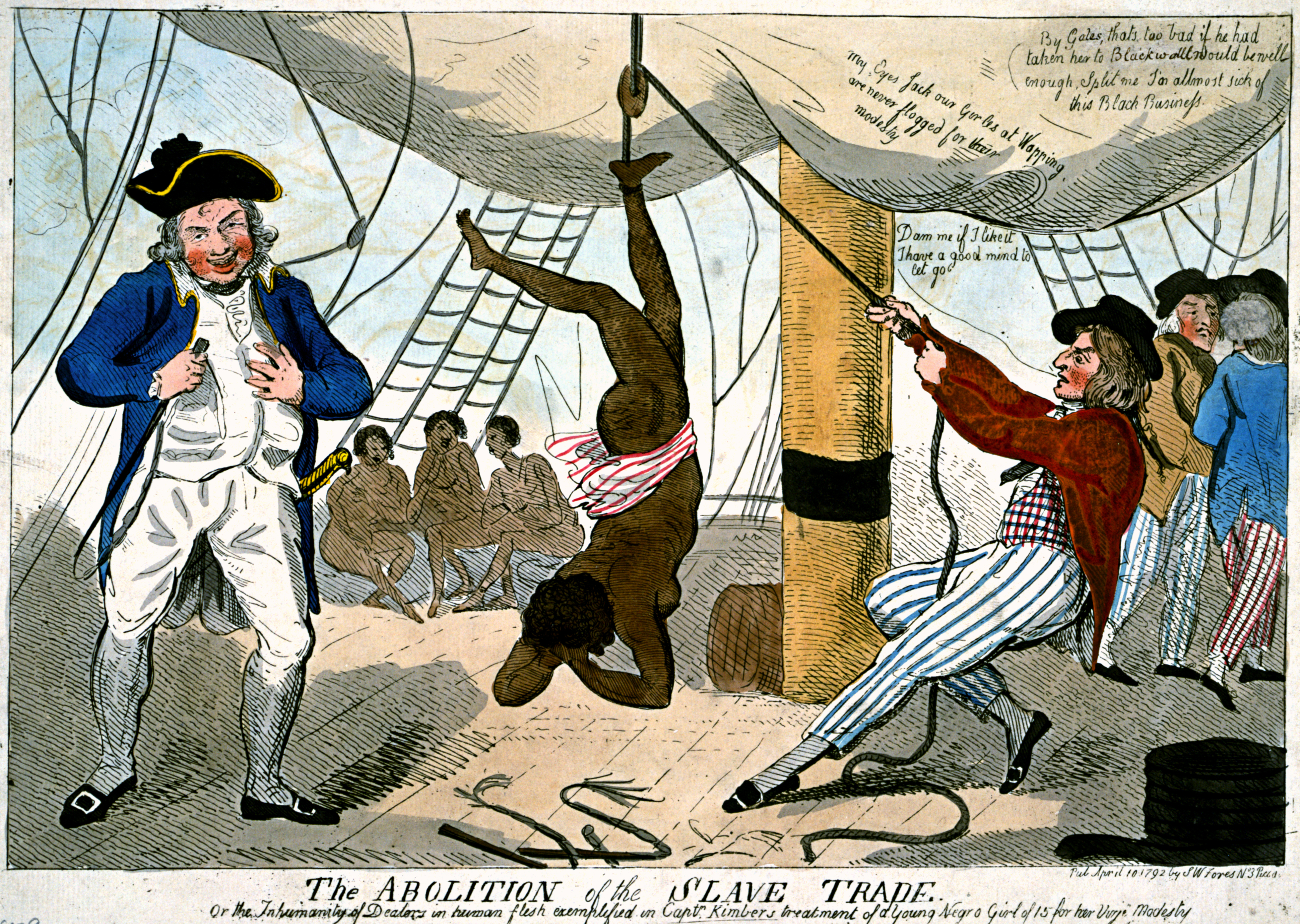

Other images were used towards the same end as Wedgewood’s, though none were quite as widespread or as effective. In 1792, John Kimber, the captain of the Recovery, was tried for the murder of two female slaves while the ship embarked on the infamous Middle Passage. While the cause of the captain’s displeasure isn’t clear, we do know that he ordered the girl hoisted up by ship’s rigging by one leg and flogged, with the process repeated on her other leg. Tragically and unsurprisingly, she died from her injuries. The image is stark, and disturbing; though in contrast to “Am I,” the image is deliberately and perversely sexualized, intended to provoke certainly, though to what end remains to be seen.

Slavery is a dark and peculiar case in the history of politically motivated imagery; but even as it is atypical (because it was the most severe of causes, because it predates the examples that followed), it is crucial to understanding how to make people understand problems they wish not to see. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade didn’t succeed in their goal for Britain until 1833, and for the United States until 1864. But that goal was in fact ultimately realized; and, in part, due to the ubiquitous image that branded the painful image of the subjection of slavery into the consciousness of those who would have, and could have, otherwise turned a blind eye.