By Hannah Rogers

Republican and liberal values supplied a significant portion of the ideology that founded the United States. This democracy formed in the 18th-century was not the only government produced by a revolution or that looked to the ideals of equality and liberty for inspiration. Despite the power placed in the hands of citizens, however, segments of the population were barred from enjoying rights of political participation. And, in opposition to this model of individual rights, slavery continued to stand as a protected and justified practice.

This conflict asserts itself in early-American fiction. The novel Sheppard Lee by Robert Montgomery Bird, for instance, illustrates the hypocrisy between “all men are created free and equal” and the enslavement of a race. A segment of the book, taking place on a Virginia plantation, follows contented slaves until a political pamphlet illustrating the horrors of slavery falls into their hands. Reading the book, suddenly the slaves develop an understanding after reading about liberalism: “A new idea had entered their brains […] for the first time in their lives, [the slaves] began to think of their master as a foe and usurper” (353).[i] This leads to a revolt on several neighboring plantations — although it is eventually put down.

Sheppard Lee, published in 1836, contains echoes of the American colonies’ — not just those contained within the borders of the United States — past with slavery. Most obviously, in 1791 the Haitian Revolution began. This revolution began as a slave revolt inspired, to some degree, by the French Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Just as the slaves in Bird’s fiction were inspired by the founding principles of the United States to take their rights, the slaves in Saint Domingue sought to fight for virtues given to more dominant segments of society. This is not to say Sheppard Lee was directly inspired by the events that created Haiti; I simply assert that the tension between democracy’s promise and its restrictions manifested itself throughout early American history in various forms.

***

The Haitian Revolution itself produced mixed reactions in the United States. According to Tim Matthewson, southern slaver holders feared that Haiti’s success would lead to the spread of rebellion.[i] Yet, citizens such as northerner Abraham Bishop, who penned “The Rights of Black Men,” supported the Haitian Revolution and believed it was “part of the great global revolution which began in 1776 and would soon sweep away the last vestiges of barbarism and slavery” (148).[ii]

As for President Thomas Jefferson, who owned slaves yet claimed to oppose slavery his policies and views toward Haiti and slavery were contradictory:

Like other Americans, Jefferson expressed a strong aversion to slavery, but it had not been possible for him to maintain anything more than a theoretical commitment to emancipation during this period of racial warfare, outhern reaction, and expansion of slavery” (38).

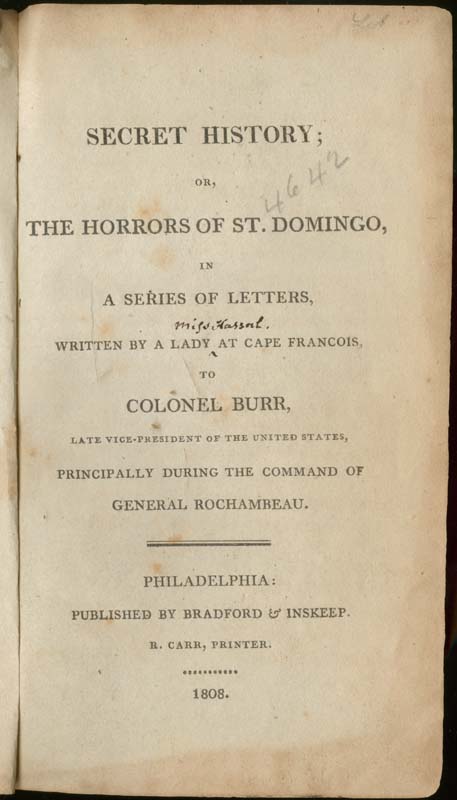

The events in Haiti inspired more than political writing and discussion, however. For instance, Lenora Sansay — an American novelist who had a relationship with Vice President Aaron Burr — traveled to Saint Domingue with her husband during the revolution and ended up writing a somewhat fictionalized account of her experiences there. The novel’s full title is Secret History; or, The Horrors of St. Domingo, in a Series of Letters Written by a Lady at Cape Francois to Col. Burr, late Vice-President of the United States, Principally During the Command of General Rochambeau. Secret Histories acts as a semi-autobiographical narration of Sansay’s time in Haiti from 1802-03. The story focuses on two sisters Mary, the narrator and friend of Burr, and Clara whose husband St. Louis who lost his plantation during the earlier period of the revolution. Clara, having married St. Louis on advice despite her lack of love for him, finds herself trapped in an unhappy and eventually abusive marriage.

The focus on Clara, who becomes caught in a failed marriage and a seduction plot, may not be the expected focus of a novel taking place during the end of the Haitian Revolution. As Elizabeth Maddock Dillon argues, however, “the focus of the novel on elite, white domestic relations against the backdrop of warfare over colonial race slavery does not bespeak sustained delusion (or colonial nostalgia) so much as an astute analysis of the relations of production and social reproduction that stand at the core of colonial politics” (78). She concludes by stating domestic reproduction in colonies would need to “think against, through, or around the presumptive sterility of the creole” and the colonial ideology (99) [iv]. There is, of course, tension in the novel between unstable nature of the creole family, and Dillon’s assessment of the early American life and the colonial shows the politics of the white property owners in Haiti. I, however, believe the novel also, intentionally or not, shows the radical break of American democracy with its own principles.

Michael Drexler puts it this way, “Leonora Sansay’s Secret History illuminates the early republic’s “unknown known”—its political unconscious—with incredible precision. It makes manifest the young republic’s dominant but repressed problem: a republic founded on liberty that held a vast population in bondage.[v]” And yet, despite his astute observation, Drexler does not specifically spend time analyzing the passages in the novel of Haitians rebelling against the French, but on the creole reactions to the revolution.

How does Sansay portray the revolutionaries then? As disloyal, bloodthirsty, insurrectionists[vi] .

It was discovered that the negroes in the own intended to join those who attacked it from without and to kill the women and children, who were shut up in their houses, without anyone to defend them..”

Former slaves turn against “family:”

[One of my Creole friends] told me that her husband was stabbed in her arms by a slave whom he had always treated as his brother; that she had seen her children killed, and her house burned, but had been herself preserved by a faithful slave.”

When a family refuses to give its eldest daughter in marriage to a revolutionary, they are hung. And when the girl refuses, she finds herself in peril:

A fate more dreadful awaited her. The monster gave her to his guard, who hung her by the throat on an iron hook in the market place where the lovely, innocent, unfortunate victim slowly expired.”

And yet, Sansay recognizes, to an extent, the desire the blacks have for freedom:

The negroes have felt during ten years the blessing of liberty, for a blessing it certainly is, however acquired, and they will not easily be deprived of it.”

Perhaps, then, Sansay only can dehumanize the former slaves by making them “dangerous” and “savage” stereotypes to deal with the tension between freedom and enslavement. Drexler, Dillon, and others question and posit answers for why Sansay and the Haitian Revolution have been forgotten and ignored until fairly recently in scholarship and history. Each answer, in one way or another, ties into the fact that the United States, and other white nations, could not imagine a black nation — even if racial equality was the next step for “all men are created free and equal.” As more segments of the population fought for liberty, the arbitrariness of these classifications made itself evident.

How does this resonate with us? For mainstream purposes, the Haitian Revolution still remains marginalized. How many history courses in United States middle or high schools teach the Haitian Revolution? While Hollywood has begun to focus on American slavery, Toussiant Louverture’s story has been unable to find a backer. Although Sansay’s novel has gained more critical attention, it has been ignored by prominent scholars.

The Haitian Revolution, and the values that became tied to it and other revolutionary nations, show the need to push back against the “established order” and find a way to recognize minority voices to avoid an exclusionary model that provides rights to some but not to all. Sansay’s novel shows us that the power of representation exists and in working with historical events and, perhaps in producing contemporary fiction, we must seek to avoid reenforcing harmful fictions. More representation of Haiti can show the direct, important connections between the events of the Haitian Revolution and the United States. By learning about the global network that produced the Americas, we can move from a U.S.-centric view to a more expansive view. I hope that by bring exposure to Haiti’s history, we can recognize modes of thinking that may encourage productive research while preventing repetition of past mistakes.

——-

[i] Bird, Robert Montgomery. Sheppard Lee, Written by Himself. New York: NYRB Classics, 2008. Print.

[ii] Matthewson, Tim. “Jefferson and the Nonrecognition of Haiti.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 140.1 (1996): 22–48.

[iii] Matthewson, Tim. “Abraham Bishop, ‘The Rights of Black Men,’ and the American Reaction to the Haitian Revolution.” The Journal of Negro History 67.2 (1982): 148–154.

[iv] Dillon, Elizabeth Maddock. “The Secret History of the Early American Novel: Leonora Sansay and Revolution in Saint Domingue.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 40.1/2 (2006): 77–103.

[v] Drexler, Michael. “The Displacement of the American Novel.” Common-Place 9.3 (2009).

[vi] Sansay, Lenora. Secret History; or, The Horrors of St. Domingo, in a Series of Letters Written by a Lady at Cape Francois to Col. Burr, late Vice-President of the United States, Principally During the Command of General Rochambeau. 1808.