Deeps > Representing Bois Caïman

Project by Lynda Berg, Sandie Blaise, Lenny Lowe, and Courtney Young

This project explores the significance of the near-mythical ceremony of Bois Caïman for Haitian cultural history. In 1791, an insurrectionary leader named Boukman, who is also believed to have been a religious leader, led conspirators in a ceremony. The various details of the story have been built up through documentary sources beginning with an early memoir in 1793 or 1794 by Antoine Dalmas. From there, the story has grown to become a potent symbol of cultural, political and religious unity for many Haitians. It evokes an image of resistance to white European brutality, political and cultural solidarity, and religious innovation. Its significance, however, has not gone without contest. It is the aim of this project to explore these contests by attending to its various representations in documentary sources, painting, music, and religious discourse.

The lack of first-hand historical accounts of the actual events of that night in 1791 mean that these various representations have come to constitute an archive in themselves. They are sometimes consonant with the earliest accounts, but in many cases they form a counter-archive, which reveals the complex afterlife of this cultural and historical touchstone.

Follow the links below to explore various representations in documentary sources, visual art, music, and religion:

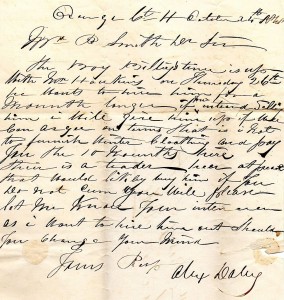

A Genealogy of Documentary Sources on Bois Caïman

A Note on Approach and Method:

This project is interdisciplinary in its approach primarily because we are a group of young scholars from diverse fields (history, theology, liberal studies, religious studies). By following our particular interests and unique methodologies as applied to the question of Bois Caiman and the narrative of Haitian history, we hope to have accomplished a couple of things:

Firstly, we hope that by grouping visual art, music, documents, and religious discourse under a common rubric, our work will illuminate pathways and trends that span these diverse representations. For example, we hope that new evangelical-influenced music will be explored alongside the pages on contemporary religious discourse. It is our hope that readers will be able to identify traces of the earliest documentary representations persisting in music, visual art, and religion. We also expect that readers will find connections that we ourselves have yet to identify by reading these pages as a single project.

Secondly, by working with all of these various representations as part of an ever-evolving archive of Bois Caiman, it is our aim to call attention to the ways that all of these circulate as “texts”, carry particular political commitments, and must be read intertextually. For example, the genealogy of documentary sources should cause us to explore when, why, and how artists, musicians, religious folks, politicians, and policy makers have engaged and continue to engage in conversation with this founding-myth.

Ultimately, we hope that our approach will at least provide a resource for other scholars and laypersons interested in Haitian history and that it will raise new and productive questions and critique.

How to cite this article: “Representing Bois Caïman,” Written by Lynda Berg, Sandie Blaise, Lenny J. Lowe, and Courtney Young (2014), Deeps, The Black Atlantic Blog, Duke University, http://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/ (accessed on (date)).

A young lady on this blog was upset with me a few weeks ago for rightly pointing out that there was a real obsession in Anglo-Saxon academia with Haitian Vodou.

While I understand that Vodou has been understudied, at least in terms of a serious religion, and that there may be something almost noble in attempting to correct this tendency, I am beginning to see this “grand project” as extremely ridiculous and unbalanced.

It’s ironic in a lot of ways.

Once upon a time, Haitians had to be ashamed because they were associated with Vodou, and now, Haitians should be ashamed if they do not associate themselves with it (or at least that is the strong impression this blog is sending). It is as if we have no agency in the matter and that culture is one fixed thing and we should never have the right to build ourself in our own terms (if those terms don’t include Vodou that is).

I also find it problematic since the only explanation this blog is providing (or suggesting rather) as to why the Haitian establishment may have wanted to suppress Vodou is a) they were ashamed of it, partly because of its association with Africa b) because of foreign opinion.

There is not even any attempts to see why Haitian, may themselves, have felt ambivalent about it because of what they had seen or heard was associated with Vodou. It’s as if unless an “outside force,” be it the government or a foreigner says whether Vodou is right or wrong, people cannot form their own judgment on it. Furthermore, it’s almost as if traditional political history did not exist anymore. It’s all about “culture” and speaking for the “voiceless” – and interpreting a whole lot, I dare say, about the voiceless…

I am all the more disappointed that this attitude is coming from academia where you would think critical thinking is a quality that was revered.

We absolutely welcome this critique. I think that you raise some important points about the way that cultural history tends to dominate histories of the West’s “others.” You are right, and that these pages seem to reinforce that may have something to do with the fact that few of those working on this project are “traditional historians” in any sense.

But, I would like to suggest that there may be a different issue at work here. You’ve been commenting primarily (in recent days) on my (Lenny’s) pages. I am, you should know, someone who studies religion specifically. So, it shouldn’t surprise that these are the issues that interest me. In the field of American Religious History, for example, the question of the evangelical roots of the American Revolution is still very much alive and animates a lot of the things written. However, that is not to suggest that evangelicalism is the only constitutive element of the United States of America. It just happens that the historical moment offers a chance to reflect more broadly on the very problematic category of “religion” and the ways that it may act as a historical force. So, firstly, I would suggest that the same thing is happening here as well. Bois Caiman has no doubt been construed as a religious event, and that “religion” has gone on to dominate Western representations of Haiti (which is your critique and mine!). I hope you’ll go back and notice that these pages are at least partly about the very issue you raise.

Secondly, you say that these pages seems unable to offer anything beyond the interpretation of a bad, mean government embarrassed by the overly-African religion. That is, again, not the argument of these pages. Instead, I’ve suggested that because of the association with Bois Caiman, Vodou comes to represent a parallel political force (and I am here following a long line of interpreters, Haitian and non- alike). I do think that the politics of respectability were often a factor (see the debate between Dr. Mars and Zora Neale Hurston, for example), but that is certainly not all that is happening.

As someone who has deep connections to a specific community in Haiti, and as one who lived there for many years, I do understand why you would be unhappy with these pages. Representations of Vodou have been a huge problem for centuries now. So, I am very sympathetic to your critique. I’m just afraid that in your justified skepticism, you haven’t paid close enough attention to the primary claims of these pages. This project is specifically about Bois Caiman and its various representations. If you explore my pages, you’ll find that they are about religion because that is what I study. But, that is not all that we’ve tried to do in these pages, and we are certainly sorry if it reads that way.

Best wishes from all of us!