by David Romine

Now here’s a little truth, open up your eyes

While you’re checking out the boom-bap, check the exercise

Take the word “overseer,” like a sample

Repeat it very quickly in a crude voice sample

Overseer, overseer, overseer, overseer

Officer, officer, officer, officer

Yeah, officer from overseer

You need a little clarity, check the similarity

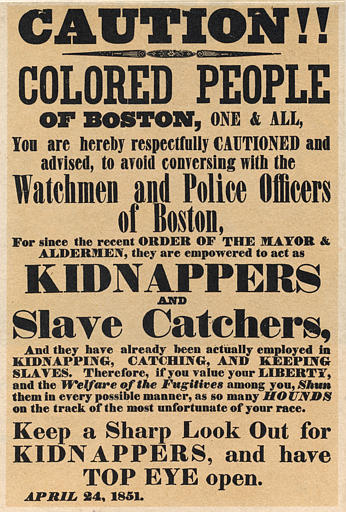

The overseer rode around the plantation

The officer is off, patrolling all the nation

The overseer could stop you what you’re doing

The officer will pull you over just when he’s pursuing

The overseer had the right to get ill

And if you fought back, the overseer had the right to kill

The officer has the right to arrest

And if you fight back they put a hole in your chest (Woop)

They both ride horses

After 400 years, I’ve got no choices

The police them have a little gun

So when I’m on the streets, I walk around with a bigger one

–KRS-One “Sound of da Police”

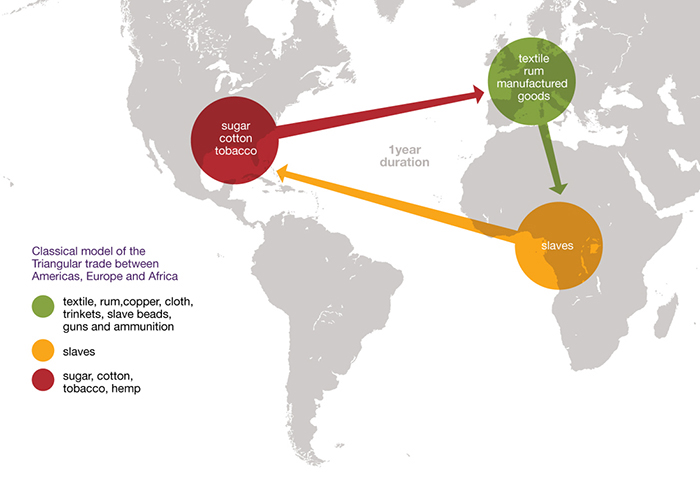

As Alisha and Andy have pointed out previously, a discussion the traumas of the Middle Passage and legacy of slavery resides in many genres of music on both sides of the Atlantic. “Sound of da Police,” one of Bronx-born rapper KRS-One’s (b. Lawrence Krisna Parker) most famous tracks, articulates the shared plight of African slaves and modern black youth by drawing a continuous line to the past, connecting the violent methods of control utilized on the plantation to that of the police in modern urban spaces. The past here is not a foreign country, but a place where people of color exist every day in a world in which police brutality is an everyday experience. Drawing comparisons between nineteenth century slavery and modern police brutality illustrate the history of African American poverty and oppression. While the forms are different, the results are the same.

Lyrics, however, are not the only connection that music draws with the past. Hip-hop as a musical form provides a unique sonic archive because it is constructed from pre-existing musical samples. The preference for soul, funk, and R&B records in the construction of hip-hop tracks, mostly from the 1950s through the 1970s, is due in part because of trend in those genres to feature songs which contain musical breaks. In mid-century music, the “break” was when a bass or drum-driven rhythm was repeated for several bars without overlaid vocals. This allowed that segment to be isolated and, with the right equipment, to be repeated. That repetition of the break through a mixing unit, functioned to create a new rhythm from the old. When paired with new lyrics or other samples, the finished result emerges as a unique, and new, work of music. This process forms the basis for the earliest examples of modern hip-hop, originating in the Bronx.

(A photo of an early sound system party DJed by one of the founders of hip-hop, Kool Herc)

The appropriation of earlier musical forms through the process of sampling also serves to create new sonic archive that resides on a register distinct from the lyrical. “Sound of da Police,” for instance, is constructed from a break in a song by legendary funk and soul group, Sly & the Family Stone. “Sing a Simple Song,” the B-side to the group’s famous track “Everyday People,” was released in 1968, arguably at the height of the band’s fame. As a song, it would have a great deal of resonance to those of KRS-One’s generation, something that they would have listened to during their childhood or that would have been playing at neighborhood sound system parties. While many casual listeners of the song might not pick up on the sample, other musicians and DJs would notice and mark it. The choice of a guitarist to utilize steel strings or electric pickups, as opposed to vinyl or acoustic, is an artistic decision which affects the construction of the song produced. The choice of sample serves the same purpose.

(Promo shot of Sly & the Family Stone c.1968)

As Russell A. Potter points out, “hip-hop’s continual citation of the sonic and verbal archives of rhythm and blues, jazz, and funk forms and re-forms the traditions it draws upon.” KRS-One’s choice of Sly & the Family Stone was both a recognition of the band’s influence and a testament to its familiarity, but arguably a reference to its politics and philosophy. In its heyday of the late 1960s, the band was politically and socially on the cutting edge. Their songs featured impassioned please for love, peace, acceptance of difference, and understanding among different peoples. Sly Stone consciously and publicly integrated his band at a time which integrated bands were still rare. Similarly, the female members not only sang backing vocals, but played instruments on stage, another rarity in a time in which most female band members were there for stage presence and backing vocals only. KRS-One’s choice of Sly & the Family Stone suggests both his political leanings and illustrates this continual revival and appropriation of past musical forms, based on their perceived value, familiarity, and utility. Early hip-hop was quite literally constructed from the soul, funk, and R&B from the 1950s and 1960s, by a generation who had listened to those records and those artists growing up. The crates of second-hand records became the DJ’s sonic archive, both a way to reference the old and create the new.

Historians generally bristle at the over-simplified idea that the past repeats itself. The distinct context of each moment means that nothing ever truly happens twice, but there can be no denying that similarities resonate from past to present. The past of African-American music is not simply the repetition of older forms, but their re-appropriation, revision, and reconstitution such that they are able to serve the needs of people in the time of their creation. In doing so, artists, producers, and DJs leave a sonic archival trail of the musical forms and ideas that they chose to utilize. Tracing this trail backwards not only leads historians on a chronological path, but it also leads those who look on a path that moves in and out of space. “Sound of da Police” as a musical archive originates in San Francisco with Sly & the Family Stone and ends up in the Bronx with KRS-One’s appropriation of the sample, but the trail does not stop there. According to the website WhoSampled?, “Sound of da Police” has been sampled over 88 times in the nearly three decades since it was released. Those samples are mostly from other American hip-hop artists, but the influence of hip-hop world-wide meant that the song moved far afield from its origins in the United States. Crossing the Atlantic, it became a part of the burgeoning French hip-hop scene through its appropriation by French DJ Cut Killer in his track for the 1995 movie “La Haine.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=SoJcACxgvFA

Cut Killer (b. 1971 as Anouar Hajoui) builds his track from a variety of samples, beginning with KRS-One’s infamous opening “Woop!”. The track also includes a distorted rendition of Edith Piaf’s famous “Non, je ne regrette rien” which the singer famously dedicated to the French Foreign Legion fighting to maintain France’s crumbling colonial empire in North Africa. Piaf’s distant, thin vocals are overlaid by short bursts of angry lyrics from the French hip-hop group, Suprême NTM. NTM, as they are also known, was a product of the Paris banlieues that encircle the city, emerging from Seine-Saint-Denis département. Seine-Saint-Denis, one of the smallest départements at 236 sq. km, also has one of the highest populations (1.5 million), 21.7% are immigrants. [edited to correct earlier mistake citing Suprême NTM as originating from Marseilles]

In addition to the sample from KRS-One and NTM, Cut Killer also includes other samples from American gangsta rappers on the American West coast (N.W.A.’s “Fuck tha Police”) and East coast (Notorious B.I.G.’s “Machine Gun Funk.”) The resulting track lacks a lyrical, linear narrative, but instead of resulting in cacophony, it emerges as pastiche, explicitly referencing the experience of the black Atlantic in the “West” through the interpolation and appropriation of sonic forms and directly connecting them to the experience of blackness in France. The violence that characterizes that relationship and the frustration that generations of young people have articulated at the system in which they live is rendered in sonic form. While many of the tracks that make up “La Haine” have lyrics, they are deliberately distorted and layered atop one another, rendering them less important than the track as a whole.

That this track was made for the 1995 French film of the same title thus seems rather fitting. “La Haine” tells the story of three young men from the banlieue, an impoverished suburb of Paris where immigrants from former French African colonies now live, and their struggle with hate, violence, and the dehumanizing, destabilizing nature of poverty. Their encounters with the authorities result in dislocation, pain, suffering, and death and their recognition that their situation is related to the French colonial past is referenced continuously throughout the film. The film, a commercial and critical success, helped bring more attention to both French hip-hop and the suffering in the banlieues, though the uprisings in 2005 suggest that attention has not been enough to improve conditions in which so many people live.

(Promo shot from “La Haine”)

The legacy of Cut Killer’s track as a pastiche of European and American forms should rather be considered a collaboration across the African diaspora. Hip-hop’s sonic archive offers a way to literally listen to the movement of ideas and shared expeeriences back and forth across the Atlantic. It is both past and present, piled up atop the legacy of the Middle Passage and colonialism, and continuously recognizing the oppression of the marginalized. The present, like the past from which it is contracted, articulates forms of resistance and testimonies of violence, the sonic archive of the black Atlantic is as rich as that of the written.

(KRS-One in 2002)