By Sasha Panaram

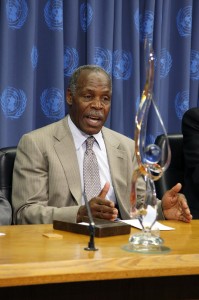

For more than twenty-five years, Danny Glover has graced the entertainment world as an actor, producer, and humanitarian. While Glover is most recognized for his role in Lethal Weapon (1987), he has also acted in much smaller films and produced projects of his own including his two latest documentaries, Concerning Violence (2013) and We Are Many (2014).

Glover’s first passion is acting, however, he has never limited himself to only one career. Instead, he leverages the attention he receives from the entertainment world to steer his fans towards meaningful social justice organizations. Today, Glover is a UNICEF Ambassador and a former Goodwill Ambassador to the United Nations Development Program.

Glover’s interest in social inequalities led him to co-found Louverture Films with Joslyn Barnes in 2005, which is committed to supporting films “of historical relevance, social purpose, commercial value, and artistic integrity.”[1] Inspired by Haitian Revolution leader, Toussaint Louverture, Louverture Films supports progressive artists, especially those from the global South, and helps train people from communities of color interested in pursuing film as a career throughout the United States.

Glover and Barnes’ Louverture Films organization is all the more inspiring in light of Glover’s deep appreciation of Louverture. In May 2012, Guardian reporter, Stuart Jeffries published an in depth interview with Glover entitled “Danny Glover: The Good Cop.” “When I talk about Haiti, it breaks my heart,” Glover told Jeffries. “Yet when I think about the Haitian people’s resilience, it heals my heart at the same time.”[2]

According to Jeffries, for more than thirty years, Glover has tried to make a biopic about Louverture. In 2006, even after assembling a cast and receiving $18 million dollars from Venezuelan president, Hugo Chávez, the film never reached completion. Part of the reason Glover wants to create a film that honors the Haitian Revolution is because he believes that previous tributes to the revolution including C.L.R. James play that featured Paul Robeson and the French TV series that starred actor, Jimmy Jean-Louis, did not capture the magnificence and full impact of the Haitian Revolution.

In searching for other filmic representations of the Haitian Revolution, I found a fifteen-minute video about Toussaint Louverture that was created three years ago for the Museum of the African Diaspora. Glover narrates the short video while Glenn Plummett plays Louverture. Dr. Cornel West and Wyclef Jean are also interviewed as part of this project.

The fifteen-minute tribute includes original music by Wyclef Jean that calls Louverture the “heartbeat of freedom.” Weaving together paintings, acting, and interviews, the tribute not only seeks to make the claim that Louverture was the primary leader of the Haitian Revolution, but also suggests by the very nature of its composition that any worthy filmic representation of the Haitian Revolution must utilize different forms of narrative expression. Most of the history is narrated from the prison cell where Louverture was confined during the last years of his life. By having Plummett, who plays Louverture, reflect on the leader’s life retrospectively, the filmmaker indicates that even when Louverture is physically at his weakest moment, his heart and mind are both still strong even as his body succumbs to death.

One of the most compelling scenes in this video features Dr. West juxtaposing descriptions of Napoleon Bonaparte and Louverture. By emphasizing Bonaparte’s limited vision and Louverture’s strong connection with his black brethren, West makes the case that the fundamental difference in the leadership styles of Bonaparte and Louverture result from their social positioning. To put differently, since Louverture was born a slave, he could identify with those enslaved and mobilize more support in a way Bonaparte could not.

While the video composed for the Museum of the African Diaspora provides a glimpse into one critical actor in the Haitian Revolution, it runs the risk of oversimplifying the revolution. For example, by not referring to Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his interactions with Louverture, the video – especially the remarks by West – make it seem like Louverture always wanted all blacks to have freedom from the start, while C.L.R. James and other historians have suggested that this was not in fact the case. Moreover, by only having one principle actor in the video, even though West and Wyclef reference the thousands of slaves who participated in the revolution and show paintings of these slaves, viewers are still left to believe that one man was responsible for the revolution.

My concerns with this short tribute to the Haitian Revolution and Louverture, in particular, lend themselves to speculations I have as to why the Haitian Revolution has not been made into a movie even though there are people, like Glover, who eagerly envision such a project. First off, there are too many people involved in the Haitian Revolution and too little space in a film to represent all of the necessary participants. Inevitably someone or some group of people would not be fully represented and this could change the way we choose to understand the Haitian Revolution. Secondly, since the Haitian Revolution lasted from 1791-1804 it is likely that some portion of the revolution would be excluded in a filmic representation and this exclusion might devalue the full weight of this historic event. Finally, as the short tribute to Louverture indicates, it would be very difficult to determine how to film a movie on the Haitian Revolution. How might a filmmaker best weave together different forms of media and art to represent the drama inherent in the revolution is a question that could not be taken lightly in this endeavor. I might supplement what I have just written by mentioning that even though a filmic representation of the Haitian Revolution might be difficult to produce this does not mean that it should not be attempted. When I reference the difficulty of determining how to represent the Haitian Revolution, my concern is less that it cannot be done someday but more that I am not sure if film studies itself has developed its capacity to represent such an intensely dramatic event. In other words, producing a film about the Haitian Revolution that actually does this moment in time justice might take several trials and errors.

In spite of my worries, a filmic representation of the Haitian Revolution would be an exceptional undertaking, because it has the possibility of resonating with so many different individuals. By having West, a university professor and activist, and Wyclef, a musician, mediate the short video, the filmmaker suggests that the Haitian Revolution’s reach is widespread and unending. If a film about the Haitian Revolution was constructed in the twenty-first century, then it could take a hint from the short video and utilize different mechanisms of storytelling to best represent the story at hand and attract as many viewers as possible.

Whether or not a film about the Haitian Revolution will be made remains to be seen. What the tribute to Louverture from the Museum of the African Diaspora makes very evident is that whatever production results will have the challenge of teaching a group of viewers about an event that both demands and deserves more attention.