By Alisha Hines

The problems of representation, authenticity, and legitimacy have always posed challenges for the producers and consumers of black culture and continue to do so. For example, Gilroy’s discussion of the disagreement between W.E.B. Du Bois and Zora Neale Hurston over the ‘authenticity’ of the Fisk Jubilee Singers is neither surprising nor unfamiliar if one considers the persistent and ongoing discourse around hip hop artists’ authenticity and legitimacy as practitioners of the art from. I would argue that this has even been institutionalized in the form of free-style battles and the sub-genre of diss-records. The dismay over contemporary black culture, though, seems to be the result of an unprecedented and widespread crisis of profitable mis-representation, illegitimacy, and inauthenticity.

It is important, though, to try to historicize these conflicts by trying to access the prevailing and dominant ethos in operation as a standard of authenticity. There are arguably many ways to arrive at a series of elements that seem to govern who gets to claim legitimacy in the hip-hop world. Yet, we would quickly run into the problematics Gilroy set forth. Legitimate to whom? And who are these terms modified in the complex global processes of production, distribution, and consumption?

If one looks closely at contemporary hip-hop music, it is apparent that Gilroy is right—the terms that define a black Atlantic diasporic cultural community has become increasingly problematic for “scholarly contemplation” as a result of complex global patterns of production and consumption.

As a result, one course to pursue these questions would be to reconsider those enduring tropes, such as the Black Atlantic as a historical or ancestral legacy. a viable basis for a contemporary political argument deployed via black musicians through musical production?

The guiding question of our exploration of the black Atlantic is what does the black Atlantic sound like? Hopefully my contributions will help illuminate the “syncretic complexity of black expressive culture” by examining the variations in the meaning of the black Atlantic depicted through sound and lyricism by black American artists.

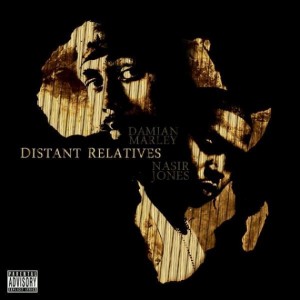

In 1998, Hype Williams released the movie Belly, in which Nasir Jones, premier rap/hip hop artist, starred as Sincere—an enlightened street criminal who fosters dreams of moving with girlfriend and newborn to Africa. The audience learns that he realized this goal by the end as the movie closes with Sincere describing the peace, contentment, and harmony he had found there. In 2010, Nas and Damien Marley released the album Distant Relatives. Themes and imagery of Africa abound in its lyrics and musical arrangement. Although slightly less vague and indistinct as representations of Africa in the movie Belly, I’d like to consider here how exactly Nas and Damien Marley have conceived of Africa and the black Atlantic more broadly in this collaborative album. Many themes I have discussed converge with the production of this album. Although Nas has not reached the heights of fame and wealth of Jay Z, the two artists are highly comparable as they share a decades long history of conflict/collaboration. Nas is considered by many one of the greatest [if not the greatest] lyricists of all time. His accolades are endless; he is currently celebrating the 20th anniversary of his landmark debut album Illmatic, and was honored by Harvard University with a fellowship in his name.

As mentioned earlier, in the past few years Nas has openly criticized the state and quality of contemporary hip hop music. Teaming up with Damien Marley, reggae artist and one of reggae legend Bob Marley’s children, to create an album of such content, then, seemed ripe material for my inquiry. The album debuted at No. 5 on the U.S. billboard chart and sold 57,000 copies in its first week. However, it didn’t receive nearly the attention any of Jay Z’s most recent albums have. I know, musical trends are seriously mysterious things, and Jay Z’s audience almost certainly spans beyond the “black Atlantic diaspora” as I am defining it here—a geographically widespread cultural community that shares or believes itself to share a distinctly traumatic racial past and present. Or to use Gilroy’s words, “those residually inherited from Africa, and those generated from the special bitterness of new world racial slavery.”[2] However, the questions still stand: Where does one locate and how does one define “authentic black culture?” More specifically, what exactly does the black Atlantic mean for these artists and how do they conceive of its functionality as a concept in their cultural production?

In the same vein as my previous essays, I want to consider just a few songs from the album in order to arrive at another set of political imaginaries for the black Atlantic and hopefully make some broader conclusions about contemporary black culture and the real and imagined history of the black Atlantic. During Nas and Marley’s interview with Tim Westwood, Nas describes the content of the album as “African history,” or more accurately, “world history.”

He claims that a major theme of the piece is telling stories that haven’t been told. Things that he and Marley know, and perhaps a certain faction of their audience may know, but that the rest of the world must be informed about. When asked about their connection to Africa as African-American and Jamaican, Marley interjects with the insight that what is more important is that “we are all human.” The point of the album for Marley, the point of relaying African history, or constructing a narrative of the black Atlantic, is to demonstrate that that past constitutes an “all-inclusive” and equal human community. Nas adds that this narrative has an emancipatory effect in the sense that he believes they have captured through the album the political ideologies of those who have risen in protest throughout the world. In The Black Atlantic, Gilroy poses the critique that contemporary black cultural production is guilty of ignoring the very place in which it locates its origins; the “problems of contemporary Africa” are almost completely absent from its concerns. He goes on to argue that this is precisely the problem that results from the conceptualization of a diasporic cultural community: “the idea of a diaspora composed of communities that are both similar and different tends to disappear somewhere between the invocations of an African motherland and the powerful critical commentaries on the immediate, local conditions in which a particular performance of a piece of music originates.”[3]

While “Africa Must Wake Up” is explicitly concerned with conditions on the African continent, conditions of poverty and disease, civil war, it is a message of uplift and empowerment directed at inhabitants of Africa.

“African Must Wake Up”

[Intro: Jr. Gong]

Morning to you man

Morning to you love

Hey, I say I say

[Chorus 2x]

Africa must wake up

The sleeping sons of Jacob

For what tomorrow may bring

May a better day come

Yesterday we were Kings

Can you tell me young ones

Who are we today

[Nas: Verse 1]

The black oasis

Ancient Africa the sacred

Awaken the sleeping giant

Science, Art is your creation

I dreamt that we could visit Old Kemet

Your history is too complex and rigid

For some western critics

They want the whole subject diminished

But Africa’s the origin of all the world’s religions

We praised bridges that carried us over

The battle front of Sudanic soldiers

The task put before us

[Chorus 2x]

[Nas: Verse 2]

Who are we today?

The slums, diseases, AIDS

We need all that to fade

We cannot be afraid

So who are we today?

We are the morning after

The make shift youth

The slave ship captured

Our Diaspora, is the final chapter

The ancestral lineage built pyramids

Americas first immigrant

The Kings sons and daughters from Nile waters

The first architect, the first philosophers, astronomers

The first prophets and doctors was

[Bridge: Jr.Gong]

Now can we all pray

Each in his own way

Teaching and Learning

And we can work it out

We’ll have a warm bed

We’ll have some warm bread

And shelter from the storm dread

And we can work it out

Mother Nature feeds all

In famine and drought

Tell those selfish in ways

Not to share us out

What’s a tree without root

Lion without tooth

A lie without truth

you hear me out

[Chorus]

Africa must wake up

The sleeping sons of Jacob

For what tomorrow may bring

May a better day come

Yesterday we were Kings

Can you tell me young ones

Who are we today

Ye lord

Africa must wake up

The sleeping sons of Jacob

For what tomorrow may bring

May some more love come

Yesterday we were Kings

I’ll tell you young blood

This world is yours today

[K’naan]

[Somali] Dadyahow daali waayey, nabada diideen

Oo ninkii doortay dinta, waadinka dillee

Oo dal markii ladhiso, waadinka dunshee

Oo daacad ninkii damcay, waadinka dooxee

Dadyahow daali waayey, nabada diideen

Oo ninkii doortay dinta, waadinka dillee

Oo dal markii ladhiso, waadinka dunshee

Oo daacad ninkii damcay, waadinka dooxee

(translation)

Oh ye people restless in the refusal of peace

and when a man chooses religion, aren’t you the one’s to kill him?

and when a country is built, aren’t you the one’s to tear it down?

and when one attempts to tell the truth, aren’t you the one’s to cut him down?

Who are we today?

Morning to you

Morning to you man

Morning to you love

“Land of Promise” carries a similar tone of empowerment but a very different set of images. The song begins with a striking juxtaposition of African countries to major cities in the United States. Nas elaborates on this theme in the second verse by deploying familiar tropes of a royal African past (“Imagine a contraption that could take us back when the world was run by black men”), and considers what a restoration of that status in the contemporary world would look like. A 21st century African-descended royalty would be marked by access to finer things. In this way, the U.S. is posed, relatively uncritically, as distinct from the downtrodden black Atlantic world and is representative of something to be aspired toward by the people of Africa.

“Land of Promise”

Imagine Ghana like California with Sunset Boulevard

Johannesburg would be Miami

Somalia like New York

With the most pretty light

The nuffest pretty car

Ever New Year the African Times Square lock-off

Imagine Lagos like Las Vegas

The Ballers dem a Ball

Angola like Atlanta

A pure plane take off

Bush Gardens inna Mali

Chicago inna Chad

Magic Kingdom inna Egypt

Philadelphia like Sudan

The Congo like Colorado

Fort Knox inna Gabon

People living in Morocco like the state of Oregon

Algeria warmer than Arizona bring your sun lotion

Early morning class of Yoga on the beach in Senegal

Ethiopia the capitol of fi di Congression

A deh so I belong

A deh di The King come from

I can see us all in limos

Jaguars and B’mos

[Dennis Brown]

Riding on the King’s Highway

[Nas]

Promised Land I picture Porsches

Basquiat Portraits

Pinky Rings realistic princesses

Heiresses bunch a Kings and Queens

Plus I picture fortunes for kids out in Port-Au-Prince

Powerless they not allowed to fit

But not about to slip

Vision Promised Land with fashion like

Madison Ave Manhattan

Saks 5th Ave and

Rodeo

Relaxing popping labels

Promise Land no fables

This where the truth’s told

Use them two holes

Above your nose

To see the proof yo!

Imagine a contraption that could take us back when

The world was run by black men

Back to the future

Anything can happen

If these are the last days

And 100-food waves come crashing down

I get some hash and pounds

Pass around the bud then watch the flood

Can’t stop apocalypse

My synopsis is catastrophic

If satellites is causing earthquakes

Will we survive it

Honestly man it’s the sign of the times

And the times at hand

[Dennis Brown]

There’s alot of work to be done, O gosh

In the Promised Land

Both songs demonstrate that the directionality of the album is eastward across the Atlantic Ocean. Unlike much of Nas’s work, poverty, drugs, violence and disparity in urban America aren’t extensively critiqued or even referenced. The artists’ conceptualization of “distant relatives,” per their comments about the content of the album, boasts an expansive and all-inclusive audience. Yet the messages offered in the lyrical content are heavily directed toward poorer African locales and especially those suffering from unrest. Although the past, namely “ancient” African history and the experience of the middle passage, is believed by the artists to be shared vastly among world’s human community, the contemporary black Atlantic diasporic experience is quite uneven. This problematic is illustrative of one of Gilroy’s conclusions in The Black Atlantic. He stated, “the globalization of vernacular forms means that our understanding of antiphony will have to change…the calls and responses converge in the tidy patterns of secret, ethnically coded dialogue…the original call is becoming harder to locate.”[4]

Follow the link to learn more about how the Black Atlantic is musically represented through the album Distant Relatives.

For full track listing: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/distant-relatives-bonus-track/id370698837

To cite this article: http://sites.duke.edu/blackatlantic/2014/05/04/distant-relatives-antiphony-and-the-original-call/

> Exploring the Black Atlantic Through Sound

> The Political Imaginaries of Black Atlantic Cultural Creation

[2] Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993. 81.

[3] Ibid., 87.

[4] Ibid., 110.