By Sandie Blaise

I went to the movie theater on Wednesday and finally saw “12 Years a Slave.” For those of you who haven’t seen it yet, it is the story of Solomon Northup, a free black man working as a musician in the state of New York, who got kidnapped in Washington D.C. in 1841 and sold into slavery in the southern states. The movie is an adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoirs, 12 Years a Slave, written in 1853. You can see the trailer here:

Beyond the actors’ performances and the movie itself – I hope they will win Academy Awards for such achievements – I wanted to talk about one of the points touched upon in the movie; the free black men abduction, and the way it reiterates the Middle Passage experience with the Mississippi River as an echo of the Atlantic Ocean.

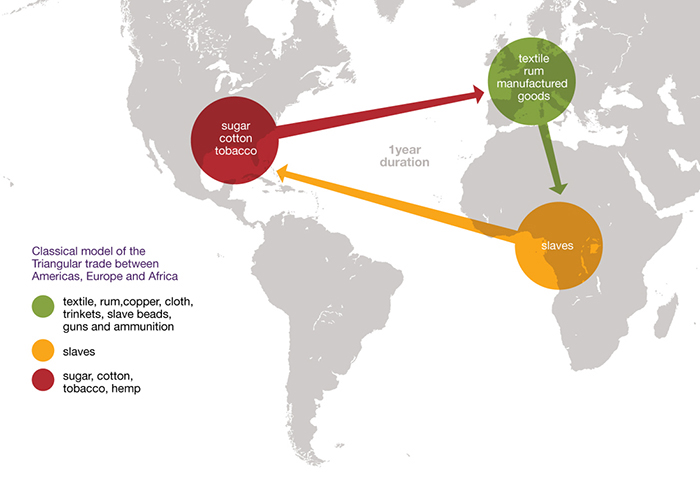

After the Middle Passage and its circular trans-Atlantic trajectory bringing slaves from the coast of Africa to Brazil, the Caribbean or the United States, before circling back to Europe with goods and then Africa to start over again, the Second Middle Passage refers to the domestic slave trade as a second forced migration within the United States.

Out of the 12 millions of slaves taken from Africa, about 250,000 were transported to the U.S.. After the slave trade ended in 1808, the U.S. was the only slave society in which slavery continued to develop naturally; slaves’ children were automatically enslaved when they were born, which increased slave population to 4 millions. The growth of the cotton industry led to the internal migration of slaves from the upper South to the lower South; indeed, from 1.5 million pounds of cotton produced in 1790, the country jumped to 35 million in 1800, 331 million in 1830 and had reached 2,275 million before the Civil War (see Ronald Bailey, “The Other Side of Slavery: Black Labor, Cotton, and Textile Industrialization in Great Britain and the United States,” Agricultural History, vol. 68, No. 2. Spring 1994).

This domestic slave migration dictated by the growth of the cotton industry shows how slavery cannot be separated from capitalism. Indeed, since cotton was an incredibly wanted good in the world; the cotton tended by slaves allowed planters to make money, so the more cotton planters wanted to grow, and the more slaves they needed to hand-pick it. Slaves were used as commodities by planters, but were also part of the Northern industrialists’ desire for profit too since by planting, tending and harvesting cotton, they were the first link of the industrial chain. They were the labor used to fulfill both planters and industrialists’ desire for profit. By moving down from the upper to the lower south where goods produced by slaves were sent to the north, the slave trade trajectory of the second Middle Passage reveals to be almost circular, too.

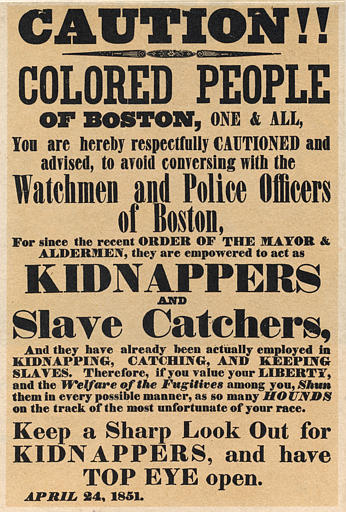

In “12 Years a Slave,” the abduction of free black men turns into what I would call a third, or an additional Middle Passage experience. After the slave trade officially stopped, and with the industrial growth of the cotton industry, slaves became a valued commodity. Slaves who had escaped slavery or former slaves who had bought their freedom and their descendants in the Northern states, like Solomon Northup, were considered free as long as they could show proof of their freedom. However, in 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act that had given effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave. Therefore, any black person unable to show free papers could be considered a fugitive, and the person supposedly bringing them in would receive money. In 1850, a second Fugitive Slave Law was enforced, stating that fugitives could not testify in their own behalf, and that no trial by jury was provided. As an effect of capitalism serving personal profit, one can easily see why the abduction of free black people developed in the Northern states. Here is an example of a poster warning free “colored people” against kidnappers in Massachusetts:

There were several cases of African Americans who had escaped slavery and lived as free men before being kidnapped and sold back into slavery; Thomas Sims, Shadrach Minkins, the Garner families, Anthony Burns, among too many others. Even though Solomon Northup was born a free man and never had to work as a slave, his story identifies him as one of them.

In the movie, one of the scenes that struck me – among many others – was when, after kidnapping Northup and other African Americans, they board a ship and sail on the Mississippi towards Louisiana. Their journey on the Mississippi River strongly reminded me of the trans-Atlantic one that their parents or ancestors had lived. Both generations experienced a brutal separation from their families and land and a manifold process of dehumanization. The presence of chains around their ankles and wrists, and sometimes even muzzles on their faces turned them into commodities, and changing their names – when sold into slavery, Solomon becomes “Platt” – denied them agency through identity, further turning them into the planters’ property.

The abducted free men also had to experience traumatic conditions on board, and the murder of one of them followed by the decision to drop him into the water while they kept sailing towards an unknown destination strongly reminded me of the trans-Atlantic journey. At their arrival, they were exhibited naked or showing their talent (playing an instrument for instance) to future buyers who could examine them like animals or objects, hence repeating the experience they or their parents had lived at their arrival in America. This “third” Middle Passage, however, was somewhat different from the trans-Atlantic one in that even though African Americans on board probably did not know exactly where they were going, they still knew what they were going to do there. They had no illusion that slavery was what awaited them.

Great post though I didn’t had the exact same feeling by watching the movie. You make a great point in saying that migration of free blacks captured in the North as well as “breed” slaves from the Mid Atlantic deported to the cotton deep South represented a third middle passage for black americans. I could not agree more. Still, in the end, you argue that this forced deportation was something different from the middle passage, and that captives knew slavery was awaiting. In my opinion, 12 years a slave shows the contrary. While blacks that were born and raised in Virginia and Maryland and then sold to southern planters probably knew what was awaiting them, this was not the case for a character like Solomon Northup, and I think the movie powerfully demonstrates that, for someone considering himself as a free men (not a free black but indeed a free man), slavery was beyond the imaginable. As I watched this movie, I really appreciated how Steve Mc Queen (not the guy from Bullit but the director) lingers on this idea of loss and terror that grips Solomon Northup throughout his journey. Unlike Tarantino in Django Unchained, he doesn’t need to show several bloodbath scenes to prove his point. On the contrary, he insists at length on the internalization of the slave-trade and plantation system violence to show that, for Solomon Northup, this world was not even remotely conceivable, it was a more like a horror’s tale, a distant dream that had affected his ancestors, and here goes the whole point in my opinion of the movie : how to pciture the reality of slavery from Solomon’s Northup point of view. In the end, this reality appears as a vivid recapturing of slavery’s violence and dehumanization while also lingering on an often forgotten point of such a reality : its denial, even by slaves who needed to escape this reality to create their own lives and intimacies. That’s why I think 12 years a slave was such a great movie and this post too by the way. Sorry for making such a huge argument on such a tiny passage from your piece. Go for Academy Awards !

One of the things that have been thrown around for months now is the notion that awards season voting bodies won’t respond to it because it’s too “difficult” to sit through. Let’s define difficult, shall we? Is it difficult to see the first openly gay politician gunned down by his closeted colleague? Is it difficult to see a reformed convict put to death by our country for his crimes? Is it difficult to see a mother choose which one of her children dies during the Holocaust? I’d argue that these answers add up to a resounding yes. Yet, no one threw those phrases of “too difficult” around.

I’ve watched hundreds of films throughout my short 29-year history and I’ve seen some difficult cinema. Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List” can make anyone quiver in shame as it shows the despicable reality of the Holocaust. Paul Greengrass’ “United 93”, which is almost an emotional biopic of America’s darkest hour, makes me want to crawl up into a ball and cry. And finally, Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ”, one of the highest grossing films of all-time, shows the labor of our sins fleshed out into the beaten skin of an honest man. And still, no one threw these hyperbolic terms out saying, “it’s too hard watch.” Is it because this is an American tragedy, done by Americans? Is it the guilt of someone’s ancestors manifesting it in your tear ducts? I can’t answer that. Only the person who says it can. The structure of this country is built on the backs and blood of slaves. But slavery didn’t just exist in America, it was everywhere. It was horrifying what occurred for over 200 years and believe it or not, still exists in some parts of the world TODAY.

Now when approaching the powerful film by McQueen and distributed by Fox Searchlight Pictures, there is a resounding honesty that McQueen and screenwriter John Ridley inhabit. There are no tricks or gimmicks, no cheap takes on a side story or character that is put there for time filling or a life-lesson for Solomon to learn. Everything is genuine. Is the film heartbreaking? Oh my God yes. Did I cry for several minutes after the screening? Embarrassingly so. I was enamored the entire time, head to toe, moment to moment.

I have long admired the talent that’s been evident in the works of Chiwetel Ejiofor. I’ve known he was capable of what he has accomplished as Solomon Northup and he hits it out of the park. He has the urgency, worry, and drive to get home to his family and executes every emotion flawlessly even when all hope seems to be lost. Where he shines incredibly are the small nuances that he takes as the story slows down, you notice aspects of Solomon that make him even more believable.

As Edwin Epps, Solomon’s last owner, Michael Fassbender digs down deep into some evil territory. Acts as the “Amon Goeth” of our tale, he is exactly what you’d expect a person who believes this should be a way of life to behave. He’s vile and strikes fear into not only the people he interacts with but with the viewers who watch. As Mrs. Epps, Sarah Paulson is just as wretched. Abusive, conniving, entitled, and I loved every second of her.

Mark my words; Lupita Nyong’o is the emotional epicenter of the entire film. The heartache, tears, and anger that will grow inside during the feature will have our beautiful “Patsey” at the core. She is the great find of our film year and will surely go on to more dynamic and passionate projects in the future. You’re watching the birth of a star.

Hans Zimmer puts forth a very pronounced score, enriched with all the subtle ticks that strike the chords of tone. One thing that cannot be denied is the exquisite camera work of Sean Bobbit. Weaving through the parts of boat and then through the grassroots of a cotton field, he puts himself in the leagues of Roger Deakins and Seamus McGarvey as one of the most innovative and exciting DP’s in the business. Especially following his work in “The Place Beyond the Pines” earlier this year. Simply marvelous.

Oscar chances, since I know many of you are wondering. Put the Oscar’s in my hands, you have a dozen nominations reap for the taking. Best Picture, Director, Lead Actor, Supporting Actor, dual Supporting Actresses, Adapted Screenplay, Production Design, Cinematography, Costume Design, Film Editing, Makeup and Hairstyling, Original Score. There’s also a strong and rich sound scope that is present. The sounds of nature as the slaves walk or as Solomon approaches his master’s house is noticed. The big question is, can it win? I haven’t seen everything yet so I cannot yet if it deserves it or not. I can say, if critics and audiences can get off this “difficult” watch nonsense and accept the cinematic endeavor as a look into our own history as told from a great auteur, there’s no reason it can’t top the night. I’m very aware that seeing this film along with Steve McQueen crowned by Oscar is nearly erasing 85 years of history in the Academy. Are they willing and ready to begin looking into new realms and allowing someone not necessarily in their inner circles to make a bold statement as McQueen and Ridley take in “12 Years a Slave?” I remain hopeful.

Thank you for your comment and great discussion on difficult movies. I agree with you on every point you make.

Just to add one thing to your statement about the “difficulty” of “12 Years a Slave” and Michael Fassbender’s performance (evil Edwin Epps), and to illustrate how difficult filming the movie must have been for everyone on the film set; I read that it was so upsetting and hard for Fassbender to play this brutal and vile character that he passed out while shooting the rape scene. His blackout in the movie wasn’t part of the script and really happened.

As for the Academy Awards ceremony, I was disappointed to see that Ejiofor didn’t get the Oscar for best actor, but the movie did get Best picture, and Nyong’o Best actress in a supporting role, at least. Now, I’m very curious to see what she will do next! She definitely is the revelation of the year.

I really do think that Lupita Nyong’o is main piece of the movie when it comes to emotional provocation. I really feel like I am seeing someone who could be really big one day.

“indeed, from 1.5 million pounds of cotton produced in 1790, the country jumped to 35 million in 1800, 331 million in 1830 and had reached 2.275 million before the Civil War (see Ronald Bailey, “The Other Side of Slavery: Black Labor, Cotton, and Textile Industrialization in Great Britain and the United States,” Agricultural History, vol. 68, No. 2. Spring 1994).”

I think you meant 2.275 BILLION.

Actually, no, I meant 2,275 million (I refer you to the article available on JSTOR or ProQuest). Thanks for catching a punctuation mistake, though! My apologies for the confusion – I will edit it now.