|

|

Exactly one week within Fez, and the city has somehow wrung, kneaded, and macerated by body and soul. It was fun. Well, from the time since landing from the six-hour flight, I’ve enjoyed even the most troublesome things. For instance, the taxi culture. Taxi drivers skin and fleece even natives of their money. At least that’s what us visitors like to console ourselves with. Utilizing varying methods to circumvent the meter system, drivers construct a uniquely yet relatively accepted realm of services where you just know the chime of pocket change will cease as you crawl out of petite taxis. Or worse, your healthy wallet unwillingly goes on a diet. In the end, this mode of transportation effectively gets me to and from school.

Taxi Stand

Although complaining about the “daily struggle” of getting my education, I realize that most Moroccan natives don’t have this privilege or choice of receiving a higher education. However, contrary to immediate assumption, this is unlikely due to their inability to pay tuition but rather a myriad of other factors. Upon my visit to Fez University, I listened haphazardly to the randomly tossed facts about the university. “Yes,” one English professor stated, “our students number around 115…” Oh, I thought, that’s not very many “…thousand students”. What? In my confused stupor, the professor continued, “And for faculty we have about 22 … thousand. The university is completely free, and some students even receive a stipend for attending.” His unnecessary pauses threw me off before I realized the immensity of what he just said. Myself being accustomed to handing over 1 ½ kidneys, a large intestine, my favorite leg (it’s the left one by the way), and the contents of my debit card, I could not for the life of me understand that Morocco offered free schooling at the university level. The sheer number of students attending this university alone, coupled with the words free and stipend, his small statement had my mind in a frenzy. From whom do they receive funding to supply education to such a large student body? How are the faculty paid? Does the nation-state have increased taxes to compensate for this? How is this possible? When I asked, he just stated “it just is”. It just is. To think my current university constructs a bill that somehow amounts to $70,000 in tuition and fees, the idea that you can get a doctorate degree for free bolted past me. Upon further inquiry, I found that that there was some recent government debate attempting to propose charging students for their education, however this was outright refuted by other government officials and the public.

A section of Fez University

This system, although mysterious to myself (and clearly to that English professor), is possible. My visit to Fez University being proof of this. Undoubtedly, if proposed by any government officials or students within the United States, this idea would immediately be disproved with varying rationale for its unfeasibility. Yet, I’m sure Morocco will continue to stand tribute for such statements refusing to think outside our $70,000 box.

Touring the Old Medina

On July 2, 2018, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) captured the first-ever clear photo of a planet birth, hopefully helping to further advance the sciences of astronomy and physics.

Another birth was celebrated that same day, on a far smaller but much more personal level. My homestay family was performing aqiqah (the Islamic baby-welcoming ceremony) for the newest member of its family, the granddaughter of my homestay mother.

I’ve been in Morocco for one week, and that was by far the most exciting experience I’ve had in the country so far. It was definitely my first time witnessing an animal sacrifice – the Muslim tradition dictates that a sheep is slaughtered on the 7th day after a child’s birth. The slaughter itself will always be etched in my brain, but the most impactful part of the whole ceremony was the intense, beautiful energy before the killing that filled the air while musicians sang and played, attendees clapped powerfully, and family members beamed with pride and happiness. It might have only been 30 people crammed into my temporary living room, but to me it was more of a rush than any other party I’ve ever been to.

While that was a literal birth, Morocco has also been a place of metaphorical birth for me; it’s been the beginning of new friendships, new classes, and new levels of exhaustion. But most importantly, Morocco might actually be a place of re-birth for me. Yesterday, on the 4th of July, I had the chance to visit a preserved Jewish synagogue dating back to the 17th century. A few days before, someone told me about the power of the presence of absence in reference to the city’s mellah (Moroccan Jewish city quarter comparable to a European ghetto). I had known about the neighborhood’s existence, but I could never imagine how striking the Jewish remnant would be. Walking into the synagogue was humbling to say the least; containing the only complete set of Moroccan synagogue fittings in existence, I knew I was breathing in history. I asked the caretaker if this synagogue was still active. She said no: only 50 Jewish families remained in Fes, and they all lived in the new, French section of the city. I then told her in my incredibly limited Darija (Moroccan Arabic) that I was Jewish: “Ana nihud.”

The caretaker opened the aron kodesh (holy ark), revealing the synagogue’s breathtaking original Sefer Torah (Torah scroll) from the 17th century. She told me that I could touch it, but that the non-Jews in the group could not. I reached out and touched the mappah (the cloth wrapping the Torah scroll) for a few seconds before removing my hand and backing away. Not really sure what to do next, I tried asking for an individual print Torah just to see it – I can’t read Hebrew – but forgetting the word Chumash, I attempted Darija again and asked for a “Torah sghir” (little Torah). I was eventually understood and given a copy. Incredibly worn out, I assumed it was very old but it was actually printed in 1973 and even published in Israel, the land Judaism was devoted to but only so recently realized. I then started carefully looking through the book, feeling worse by the minute because I couldn’t read my own people’s language. I closed the book and prayed over it nonetheless, promising to G-d that I would work harder to learn the language of my heritage and connect deeper to my religious roots.

After praying, I then climbed upstairs to the roof to see the nearby Jewish cemetery; expecting a small gravesite, I was confronted by a wave of white tombs that stretched further than I could see from the synagogue terrace. That’s the moment I was truly hit by the presence of absence.

There are far more dead Jewish people in Fes than there would ever again be living ones.

Morocco once had a thriving Jewish community, between 250-300,000 people prior to the creation of Israel, and now all that’s left is maybe 3,000 Jews in all of Morocco. Knowing how vital the community once was, I’m deeply saddened by the present reality. But history’s history. So while there’s nothing I can do to create a Jewish Renaissance (Tehiya in Hebrew), I can at least try and find rebirth within myself.

My eyes drooped at the midnight table as my head sagged close to my steaming ceramic bowl and loaf of khubz. I carefully checked the watch on my wrist, not to wanting question my family’s hospitality. A quarter past twelve. I sighed to myself, completely exhausted. Picking up my spoon with the dexterity of a toddler, I began to move the lentil soup from the bowl into my mouth. Half-asleep, my spoon scraped the bottom, collecting the last drops of food. The sound was like an alarm to my host-mom as she quickly eyed me. “More?” she asked, speaking in indecipherable Darija. “No, thank you” I gestured, moving my hand from my mouth to my heart. I wasn’t so much hungry as I was parched, relying solely on the rare water bottle, mint tea, and cloyingly sweet coffee to quench my thirst. As the night grew, the house seemed to become more alive. Out of the heat of the sun, children ran around and the women sat and gossiped among themselves. There was always something to be doing and never time to rest. My host-mom was almost constantly a presence in the kitchen, making food or tea, and when she wasn’t, she was cleaning the home. I wanted to ask if I could do anything, but I knew my help wouldn’t be accepted. For Moroccans, there was always time to eat, but it seemed like there was never time to digest. While I wanted to remain present and socialize and try out my limited Arabic, I also needed to do homework and get some rest. Exploring the Fes Medina had worn me out in addition to my already going to classes and becoming accustomed to a new culture. But when the call of the muezzin shook the house at four o’clock each morning, I realized that sleep wasn’t in the Moroccan dialect. My family never skipped a meal or a prayer, but foregoing bed was a habit. Maybe there was something in the tea that kept them vigilant; but, whatever it was, it hadn’t been passed on to me.

One morning as I stepped out of the bathroom, I was met by the sight of my host-brother, Wafi, corralling a sheep into the living room. He explained to me that he bought it at the market for the celebration of his newly born daughter— a gathering I was invited to attend the following day. It is customary for Muslims to perform sacrifice seven days after the birth of a child if they can. They call it an aqiqah. The celebration included traditional music and dance and mass quantities of food and mint tea. They had invited their neighbors, relatives, and other good friends, all packed in together in a small room. The men and women wore their djellabas and the house was decorated in pink and white lace. As the music reached the height of its intensity, Wafi and another man flipped the sheep onto its back. Wafi brandished a knife and slit the animal through its throat. Blood pooled on the tile floor and the guests cheered and the music roared. At the lunch which followed, I asked Wafi what they decided to name their daughter. “Ghita,” he told me. The only thing I could think was how it would be impossible for any Westerner to ever say her name. Unlike our names in the West, Arabic names are full of meaning and history. Many people have the same name because their parents want the connotation of the name to be passed onto their child. It was clear that tradition ruled each facet of the Moroccan lifestyle. It flowed through every bustling street and narrow alley. It permeated the towering mosques and the tiled homes. It was a tradition of faith, a tradition of longstanding culture. That’s what it meant to be Moroccan, and if I wanted to learn, there would be no time for sleep.

The table setting from the aqiqah

“Kulī, kulī!” Mina insists. She gestures to the plate in the center of the table, looking at me imploringly.

I smile and nod as I let her serve me another piece of cake. I make eye contact with my roommate Molly as she accepts another slice as well.

Mina is our host mother here in Fez. She lives in the Old Medina with her husband and three adult children, and, from what I can gather, she does most of the cooking in the house. Tonight, she is serving peanut butter cake as the first course of dinner. The cake is excellent—moist and flavorful, with a thick, peanut butter frosting—but we have had cake for breakfast three times in as many days and for kskaraT, snack, too.

“Kulī, kulī!” Mina chirps again. She has noticed that the progress on our cake is slowing.

We smile at her and simultaneously eat another bite of cake.

Kulī: the imperative of eat. It is a phrase we have become accustomed to hearing in the short time we have stayed with Mina. If Molly or I ever pause during our meal, Mina will insist, “Kulī! Kulī!” until we resume eating. In a way, I find Mina’s demands endearing. She just wants to make sure we get enough to eat and don’t go to bed hungry.

But she needn’t worry. I haven’t felt hungry since arriving in Fez.

I read that the diabetes rate in Morocco is much higher than the mean for the region—the fourth highest in the Middle East and North Africa. As I nibble at my peanut butter cake, I can see why. Moroccans eat what I would call four square meals a day—breakfast, lunch, snack, and dinner. Moroccan tea, flavored with mint and sweetened with an exorbitant amount of sugar, accompanies each meal, along with chants of “Kulī, kulī!” until Molly and I are unable to eat any more. The food Mina prepares tastes wonderful—we eat a lot of fresh khobz, bread, and beghrir, sponge cake-like pancakes slathered in honey. However, after only a few days here, I am craving a fresh vegetable.

I wonder what factors influence Moroccan people’s diets. In the United States, where diabetes and obesity also plague the population, “healthy” foods like fresh produce are more expensive than their processed counterparts. I wonder if the same rings true here. Are bread and honey simply more affordable than fruits and vegetables? Or is it tradition that compels Mina to prepare sweets for every meal? Perhaps these are the recipes passed down to her from generations and generations of sweet-toothed Moroccans. Or maybe, I think, looking around the table at Mina’s family as they lick frosting off their fingers, gathering the whole family together for a home-cooked meal is more important than the nutritional value of the meal itself.

I hate to admit that I do not know enough about Moroccan history and culture to know the definitive answers to my own questions. Mina takes our empty plates back to the kitchen as I struggle to think of a sustainable workout regimen for my time in Fez. If I’m going to be eating cake for dinner for the next six weeks, I’ll need to find some time for cardio.

Mina emerges from the kitchen and I crane my neck to see what is on the plate she is bringing to the table. She sets it down in front of me and I my heart almost skips a beat as she returns to the kitchen—pasta! My taste buds water over the thought of something savory. But then Mina appears with the sugar bowl, and my hopes are dashed as I watch her douse the undressed pasta in sugar and cinnamon.

Mina hands Molly and I each a spoon and sits at the table. “Kulī,” she declares, grinning warmly.

I try not to raise my eyebrows as I make eye contact with Molly again. Sugar on pasta? We cock our heads knowingly at each other. When in Rome. Stifling laughter, we pick up our spoons. We dig in.

Dinner in Fez – angel hair pasta with cinnamon and sugar.

Stepping into the Casablanca airport two weeks ago, I wasn’t struck with any sort of magical, different-feeling feeling. Somehow, I had expected to be filled to the brim with some kind of sensation of Morocco, the intense feeling that I had entered into a place that was different than the one from which I came.

Instead, I looked around and thought, “Okay, I’m in an airport.”

It was an airport like many others I’d been to before. I stood in the customs line for far too long with my dad, sister, and roommate Bailey, we picked up our suitcases, and found a taxi to the hotel. Almost immediately, I started to feel very uncomfortable. After studying Fusha Arabic for the past two semesters, I had expected to know at least a few useful phrases and had thought that I’d do alright communicating in Morocco. I was definitely wrong about this, and the few things that I tried to say were clearly not well received and/or made no sense. I felt a lot of responsibility for my family who had only come to Morocco on the way to another destination and spoke no Arabic at all.

After a whole day walking around Casablanca, deflecting people trying to sell us things, unsuccessfully speaking Arabic, getting lost, and feeling overwhelmed in several other ways, I sat on the train back to the hotel with only one thought running through my head over and over.

I wanted to leave.

As much fun as I had had that day, I was also freaking out. How could I want to leave? I’d been looking forward to this trip to Morocco for months, ready to learn more Arabic and travel around somewhere new. I had chosen to pass up on spending another summer with my family and friends and continuing my fun summer jobs. I had decided so certainly that this was something I wanted to do, but I could think of nothing other than how much I needed to get on the first plane back to New York. I could not spend six entire weeks this far away from my home.

I sat in bed in the hotel that evening trying to rationalize all of my thoughts, trying to figure out how disappointed in myself I would be (and how much the Duke withdrawal fee would be) if I threw in the towel and went home immediately. After texting some friends and having a night of sleep, I felt slightly less worried, but still very concerned about what I was going to do.

Perhaps luckily, the next day, we traveled to spend the week in Spain where my worries slowly evaporated, and eventually we returned, with another week of travel under our belts and genuinely excited to get to our host home in Fez and unpack our suitcases and sleep in the same bed for more than one night at a time. Our host family doesn’t speak much English, and we don’t speak much Darija, but each day in Fez brings more comfort and normality.

I was (I am) afraid of sexual harassment, getting lost, getting ripped off, not understanding the language, and being in a new place for so long. Pretty much all those fears have indeed come true, but not at the expense of me wanting to be here. The longer I’m in Fez, the more at home I feel. I don’t feel like the “Moroccan version” of me, or like I’ve been irrevocably altered by being somewhere that isn’t the United States of America for just one week, but I do feel like me.

Besides the fun excursions, learning new language, and traveling with friends, the part of Morocco I’ve enjoyed the most is falling into the routine and rhythm of Fez. I wake up, I catch the taxi to school, I study in the courtyard or a café, I walk around the city looking for new places to eat, I have dinner way too late at night, I wake up every morning at 4 am when I hear the call to prayer, and mostly I just exist, the same as I always have- in Fez, a city that is vibrant and uncomfortable and intriguing and unfamiliar and very, very fun. Day by day I’m learning how to be me in Morocco, and I’m really excited for the next five weeks.

Pictured: Bailey and me at The Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco

My engagement with the word citizenship is limited to the citizenship awards that used to be given out in elementary school. My notion of it is limited to acts of kindness among classmates, and of thoughtful students ready to help the teacher out in any way. This has been an emergence into literature that is, I argue, relevant to the life of a proactive citizen.

But it hasn’t been all academics. Within the week we’ve been here, I’ve been propelled to think critically about the culture around me and what I learned through my first year in college to be “Modernization Theory.” Through the trajectory of my education, it was always implied that the path to modernization was one and linear, with the endpoint being a fully capitalist society like the US. The latest technology and a goal to discontinue anything “old-fashioned.”

However, it is evident that “modernization” shouldn’t be restricted to single path, or a single endpoint at that. While Americans boast modernity above all, with self-driving cars, next-day shipping, and the ubiquity of the latest technology, Morocco, by American standards would be lagging behind.

Why use American standards though? These are arbitrary, and the same path can’t be assigned to a country that’s different from the US in every sense of the word.

This thought will be left unfinished, as I will have to think about this more over the coming weeks to form my concluding thought.

Women’s rights are human rights. This is a universal truth. Over the past year, I’ve been struggling with discerning between Western feminism and universal feminism. On Sunday, our group attended a performance by the American Center’s drama club on gender violence. It was a moving performance. The following are quotes that caught my attention and forced me to reflect:

“I want to apologize to every woman I’ve called beautiful before I’ve called intelligent”

“Slut-shaming culture is rape culture”

These are universal truths, and I felt hope because from the very mouths of these Moroccan women, I found common ground between the feminism seen in the West and the feminism seen here. The feminist movement should aim to be on the same page globally, and the more I’ve explored feminism at the university level, the bigger the divide between regional feminisms. It was good to feel hope that maybe we’re not so different. There is a solidarity between women across continents that I’d never encountered, so I never knew how real and how strong it was. The spirit of defiance against gender violence was palpable as women claimed their right to safety on the stage.

Bread and Bliss

When I decided to go to Morocco this summer, I didn’t do any research on the places I’d be visiting because I just wanted to travel there and get the full experience without having any expectations. I heard from friends that Morocco has a very rich and ancient culture and that, I came to confirm was true. But there were many things that I was surprised to discover both during my short stay at Casablanca before taking the train to Fez and during my tour of this beautiful city. Having lived in Kenya almost all my life and an image of the stereotypical city of a developing country in my mind, touring Morocco was a big of a shock for me. The streets of Fez are so much cleaner than I expected and very well maintained. At first, I thought it was just the city center that was kept clean to give a good image of the city in general but now I have been to different parts of the city and every street I have been to is so clean and properly maintained, with beautiful trees planted along every street and flowers at every roundabout. Even the Medina, which was founded in the 9th century and with such narrow streets and alleyways and donkeys carrying goods around, you’ll hardly see any garbage around.

Figure 1: A Street in Fez

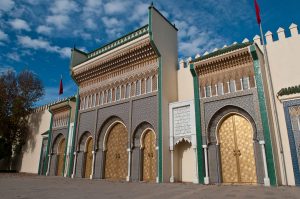

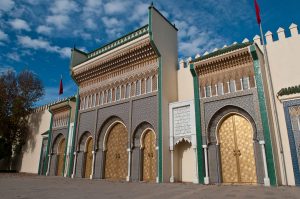

Fig 2: Kids swim in a roundabout fountain next to Dar al-Makhzen, the Royal palace at Fez

Figure 3: Dar al-Makhzen

What was even more surprising was the fact that these streets are usually full with people even past midnight. That was in fact the first thing I noticed when I arrived at Fez almost half past midnight and found so many people seated on benches around the Batha roundabout while I waited for my host family to come pick me up. I was also amazed at the fact that there aren’t many traffic lights and no traffic police at all to man the streets, yet there isn’t any traffic jam nor are there road accidents or any sort of disorderliness!

Khobz: this is the Arabic word for bread. Moroccans love mint tea, that I knew, but their love for bread? That was entirely new and was another thing that has been worth noting. Fassis- people of Fez- usually serve bread at every meal. They eat bread at breakfast and at lunch and even at dinner. You’ll go to a hotel, ask for a hot chocolate and it comes with khobz!

Fig 4: Khobz Fig 4: Khobz

I have been here barely a week now and I feel like I have seen and learnt so much. I can’t wait to explore Morocco more in the next five weeks.. I’ll be spending the next two weeks at Fez before moving to Rabat for the second part of this program but I’ll also be traveling to Chefchaoeun, Meknes and most importantly will go on a three-day trip to the Sahara Desert soon so stay tuned for more about my adventure in Morocco every Wednesday!

A House in Fez, by Suzanne Clark, takes the reader on a journey through the complexities of a foreigner’s life in Fez. Through the everyday highs and lows, the reader experiences a willingness to accept an adventure where many others would comfortably decline.

Clark and her husband embark on the mission to buy a house in Fez, Morocco, and restore it to its original glory. This is easier said than done: both are limited in their French and Darija, respectively, and there is the issue of a language barrier. That is to be the least of their concerns, as they soon realize Moroccan bureaucracy is a series of exponentially growing obstacles, fueled both by Moroccan’s relaxed lifestyle and an increasing Western-like demand for accountability.

There are three themes within the book that are strikingly important as they connect it to the world around it. Neocolonialism, the intricateness of being a global citizen, and an interesting irony (or juxtaposition) where the white person becomes the foreigner, are the three themes that will be discussed.

Throughout the book, Clark consistently characterizes and emphasizes “neocolonizers” without explicitly calling them so, while simultaneously attempting to differentiate herself from them. By regarding these differences, Clark sets the standards for what it means to be a colonizer, and what it means to be a global citizen as a white woman in Morocco.

As Clark and her partner begin the adventure of buying a house and restoring it, it becomes increasingly evident that she is not the only foreigner to have thought of this idea. Clark reveals herself as a neocolonizer with a hint of the white savior complex, almost as if claiming that Fes and its cultural treasures are for her to own, explore, and save. The Culture’s Keeper, almost. What differentiates her from the rest of the foreigners also buying houses in Morocco is her undeniable desire to restore her riad to its formal glory. Modernizing it as minimally as possible and requiring the help of special craftsmen to not damage the artistic architecture, she argues, reveals a determination unique to those few that care for the cultural preservation of Morocco.

This is an almost heroic feat. Clark, having not moral obligation to Morocco, spends much time and money in this restoration, taking care to get things done right. However, it is her underlying intentions that make these grand actions questionable.

Clark often uses an almost condescending way to think about her own actions in relation to those around her. By her standards, her actions are more valid than a local’s would be, all because she has the luxury of choosing to preserve historical architecture. She often judges locals for their failure to upkeep historical architecture, but what she fails to realize is that her opinion doesn’t matter when she doesn’t have the struggles most Moroccan people have.

There is a tension between Clark’s longing to belong in the Fes community and her actual sense of belonging. She failed to convince this reader that she belonged in Fes. Instead of admitting her lack of knowledge and her room for growth, she insisted on critiquing foreigners in her similar position to elevate her status within an arbitrary scale to herself.

However, this is not surprising as it is easy to imagine how difficult it must be for a white person to feel like the outsider. It is understandable that her first instinct was to attempt to validate her actions, even if it meant discrediting others’. She no doubt was right in cases where she complained about people’s lack of initiative in adapting to the new culture, but these are standards that she’s made to judge foreigners in Morocco, and she herself is a foreigner. It would make more sense for her to use a Moroccan’s scale of what it means to be a foreigner that is welcome and belongs in Morocco. This and her critique of Moroccan locals based on their :failure” to keep artistic architecture intact alienates her further from the community she tries so much to integrate herself into.

Overall, the work is a must-read for anyone new to Moroccan, or even Arab culture. The work has a lot of potential in terms of it highlighting what it is that foreigners should know and keep in mind when traveling to a country like Morocco. There are many introductory terms that will help those who are new to Morocco to appreciate what they will be seeing. While one may disagree with the thoughts and actions of the author throughout the book, her “relateableness” as a foreigner to the Arab World and her willingness to explore should be appreciated. There is no “How to Travel in Morocco for Dummies” book out there, but this is the closest thing to it.

A Courtyard in the Riad A Review of A House in Fez by Suzanna Clark

Fez is one of the few remaining medieval cities in the world and predates “modern” urban centers like New York or Brisbane, Suzanna Clarke’s home city. Although no person or corporation, including Google, knows every street and back alley of Fez’s Medina, there is a sense of structure to the Old City that is not immediately evident to first-timers. As our guide told us yesterday, Fez is organized into sections related to either commercial or residential areas and designed to moderate temperature. Even in the short two days that I have experienced Fez, I have started to learn just how difficult it is to accurately summarize and appreciate the complex culture and people of Fez.

Suzanna Clarke, a self-proclaimed photojournalist and blogger, attempts this feat in A House in Fez. Her account takes place over a decade ago, when tourism in Fez was limited. While leading a group of Europeans through Morocco, Clarke and her husband grow tired of the sterile modernity of the five-star hotels her clients desire. Their personal appreciation of Moroccan architecture prompts Clarke and her husband to purchase a riad, or a large house, in the Fez Medina.

Clarke constructs her narrative around the restoration of this riad. Through this framework, Clarke aims to “journey into Moroccan customs and lore” and provide “a window into the lives of its people” (back cover). Clarke’s description of the restoration process is impressively detailed, however, her claim to authenticity falters with her struggle to reconcile her role in modernization and her one-dimensional characterization of the people she interacts with.

Although she is relatively new to Morocco, Clarke states she does not have the typical Western approach to living there. In the first few chapters, Clarke glorifies the communal support and craftsmanship of her adopted city. She also claims to appreciate the city and its people more than the typical tourists she and her husband guide through Morocco. Clarke clearly admires the Moroccan aesthetic and hopes to restore her home by utilizing its traditional craftsmen and materials. This task consumes most of her writing, but she also includes information on Moroccan culture through descriptions of wedding practices, religion, family life, and more. Along the way, Clarke adopts local pets – some animal and some human – and tries to become a part of Moroccan scenery.

The most engaging aspect of Clarke’s writing was about the restoration process itself. Early in process, she describes the “feral spaghetti” of cables that dominate her courtyard. This vivid image underscores the evolution of the house’s structure. While the cables were not original components of the home, they speak to the changes the riad has witnessed over time. In another instance, she returns a room to a more original form when she adds a halka, or a decorative atrium, to the kitchen (181). This change creates more open space and showcases the massreiya on the ceiling above. Her careful reasoning behind this alteration speaks to her adherence to detail and her respect for elements of the past.

Clarke’s contradictory writing celebrates the old, yet struggles to accept her part in contributing to the new. When she begins her book, she wants to “find a house that had been spared the process of modernization,” since current renovations often result in the loss of a home’s ornamentation in Fez (18). Clarke compares the renovations of some riads to colonial times, but when her husband compares her to a colonial administrator on pay day, she protests by stating that she pays her workers well. What she fails to acknowledge is that she occupies a similar position of power, even if the level of exploitation is not the same. Her decision to learn French, the language of Morocco’s former colonizers, rather than Darija, the local Arabic dialect, only exacerbates this issue and leads to communication problems throughout her story. Clarke echoes her distaste for modernity again when she visits Marrakesh, where she is “dismayed to see a modern, fluorescent-lit boutique between the stalls” (219). Once again, she acknowledges that Western culture drives these changes, but does not address how she might work against it or that she even plays a part in Marrakesh’s tourist culture to begin with. While Clarke is entitled to her own tastes, she presumes that she has a right to dictate the tastes of others.

Throughout the book, Clarke characterizes Moroccans as hard to understand and backwards. When she describes her neighbor Khadija, Clarke focuses on her poverty and difficulty communicating (43). Khadija is treated as entertaining at times, but mostly seems like a nuisance when she comes with the added baggage of her family. Clarke’s complaints ignore the strong role of family in Moroccan culture. Ayisha, another local woman, falls into a similar category of cluelessness. She shares her belief in djinn, her love life, and her family’s celebrations with Clarke, who responds by viewing these things as odd or naïve (243). Some of these impressions hold true, but Clarke generalizes Ayisha’s beliefs to represent typical Fassi life instead of considering the different experiences each of Fez’s 1.1 million residents. Given that most of Clarke’s friends are expats, her fairly narrow view of Fez’s people is understandable. However, if A House in Fez journeys into Moroccan customs and lore, Clarke rarely goes off the beaten path.

A House in Fez appeals to its audience through its promise of revitalization, and although it has strong redeeming qualities, its occasionally patronizing tone hinders its ability to give an accurate representation of culture in Morocco. Although I could easily imagine the buildings of Fez and some of its cultural practices, Suzanna’s “friends” in Fez were too often paper-cut-outs, rather than real people. This characterization, paired with Clarke’s white-savior complex, made the book an informative read, but it was not a full picture of the Moroccan culture I have experienced so far. Clarke assumes that her personal experience renovating the house provides key insight to Moroccan culture and norms. While she successfully restores her house, the limitations of her language, Western perspective, and social circle hinders a nuanced account of Moroccan culture.

Alexander Frumkin

01 July 2018

DAW 2018

“When we mentioned our fantasy of buying a traditional Arab-style riad, or courtyard house, in Fez to a friend, he said dismissively, ‘What a terribly nineteenth-century thing to do’.” (Clarke 7) I thought the author would refer to colonialism – the Scramble for Africa started in the late 1800s, after all – but Clarke instead introduces an interesting anecdote about early European women travelers. Clarke often addresses the comparison of her actions to 21st-century colonialism, but for someone as conscious about her actions, there are several elements in her story that are off-putting considering how genuine the author’s efforts and rhetoric appear. This book should not garner recognition from academic circles, but it clearly was not written for the sake of academia. It’s the story of one couple trying to admire a culture in a uniquely human manner.

A House in Fez, by Suzanna Clarke, is a memoir encompassing the extensive completion of her Moroccan home (Riad Zany). Clarke and her husband, an Australian couple, decide to move to Fes after only visiting twice, despite the fact that they share almost nothing in common with the people or culture of the city and don’t even speak Darija (Moroccan Arabic). What follows is a years-long journey in order to restore a home in the Fes Medina to both preserve a historic building and adapt it for a modern lifestyle; the book largely details this construction process, but it also almost seamlessly weaves some of the history and culture of Fes into the narrative by fitting well-written stories into the book’s chronology and reflecting on these addressed realities. A House in Fez, despite its inability to inform readers on aspects of Moroccan culture without evoking thoughts of orientalism, white guilt, and the white savior complex, is a book worth reading for those interested in visiting Morocco because of both its fun, easily accessible nature and its consideration of distinctions between the culture tourists most likely experience at home and the one they will experience in Fez.

As Clarke goes about her journey in Morocco, she expresses a strong passion for the culture in Moroccan culture, but no rationale is ever provided for this. In combination with the fact that Clarke does not appear to adjust her lifestyle culturally to the way of life in Fes-el-Bali and does not even attempt to learn Darija, it is very difficult to not make connections to Edward Said’s analysis of orientalism. While the author never suggests any belief that culture in Morocco is inferior to that of the Western world, she does state at one point that, “The romance of having no hot water … had soured. … I had to admit I was a spoiled Westerner who found it hard to go backward in my living standard.” (Clarke 155-156) This is not the same as Said’s theorized patronization of Middle Eastern culture, but the truth remains that it is reminiscent of the fetishization of the Middle East – and incredibly close to saying that life in Morocco is worse than life in the “developed” world. If that’s the case, then why is Clarke so driven to live there?

In turn, that is where the concerns of white guilt and the white savior complex arise. Consistently throughout the memoir, Clarke compares the monetary situations of herself and those around her. Despite calling herself a wage slave (Clarke 5), she also makes it very clear that giving up on work to move to a brand-new country and self-finance the construction of a new home is – for the most part – a financially accessible option. She then consistently laments about how wealthy she and her husband are in comparison to their neighbors; as a result of this white guilt (at least wealth-based if not race-based), she frequently expresses a desire to pay her contracted employees well, almost as if she is trying to absolve herself of said guilt. Clarke never verbally recognizes this, but she does several times address “rescuing” the Medina, its people, and its culture. By acknowledging the idea of the white savior complex without ever genuinely considering the similarities between it and her actions in Morocco, Clarke appears hypocritical, and it is the book’s deepest flaw. However, as flawed as it may be, it is mostly the result of the lens of Western ethnocentrism that she has spent her life looking through; Clarke clearly does want to help restore the Medina, and by no means does she ever express that only white people are capable of doing this. But by failing to address the efforts of Fassis attempting to do the same things, it unintentionally lessens her memoir.

Despite all of this, A House in Fez is still worth reading.

As much as I dislike certain aspects of Clarke’s narrative, I was drawn to her writing style. She successfully captivated me into reading a 270-page story that at the end of the day is really just a novelized version of HGTV. By incorporating methodically including Moroccan history, the culture of Fes, and stories of all the people she meets along the way, Clarke created a novel that is enjoyable, informative, and accessible. She uses interesting analogies and descriptive language to paint an intriguing picture of Fes, the spiritual capital of Morocco. Clarke’s most redeeming quality was her refreshingly genuine voice that could be felt during the entire novel. She may express the distinctions between culture in the West and culture in the Medina in a somewhat problematic manner, it is a result of her upbringing and clearly communicates her purpose to her audience. This book is not for historians or academics that study culture, but it is for people who want a glimpse at life in Fez from someone who sees the world in a way that resonates with them. So while I disagree with the lack of self-consciousness from someone as apparently conscious as Clarke and believe more could be done to make this a better, more culturally nuanced memoir, I can relate to the author’s perspective and I would argue that the book marginally improved my perspective on life in Fes. It is a book that should only be a minor piece of any tourist’s inquiry into the culture of the city; it should not be the first source someone reads before planning a visit, but it serves as a nice complement to those who already have a fair understanding of the history and culture of Morocco and want to read a unique Western perspective that connects on a human level.

Clarke, Suzanna. A House in Fez: Building a Life in the Ancient Heart of Morocco. Pocket Books, 2008.

Far away is the luxury of running water, take-out Chinese, and pre-sliced mushrooms for Australian author, blogger, and part-time remodeler Suzanna Clarke when she embarks on her journey to buy and – with excruciating attention to detail – restore a riad in the medieval Medina of Fez, Morocco. Suzanna Clarke’s A House in Fez focuses on the historical importance of the preservation of ancient buildings in Fez, despite the temptation to modernize certain aspects of the house or to skimp on the restoration process to reduce time and expense. In a city that is developing rapidly due to tourism and technological innovation, maintenance of the ancient Medina is becoming more difficult than ever, especially when considering the cost of restoring a dar or riad to its original state. While Clarke addresses the mounting issues due to tourism and provides valuable insights into of Moroccan culture, she fails to show her perspective through anything but a westernized perspective or to provide a viable solution to the restoration-cum-modernization of the Fez Medina, all while constantly making comparisons between life in the ‘undeveloped’ city of Fez and her westernized life in Australia.

A House in Fez begins with Clarke’s journey to Fez to find a suitable home for her and her husband, Sandy. They eventually decide on a run-down riad in the oldest part of the Medina. After purchasing the home, the grueling restoration process begins, along which Suzanna encounters many trials and tribulations; learning to manage the (sometimes slippery) contractors, find proper building supplies (without being fleeced), and navigate convoluted Moroccan bureaucracy proves to be no simple undertaking. After seven months of nonstop work on the riad– almost to its completion – Clarke returns to the hustle and bustle of her life in Australia, heart heavy with longing to return to her newfound home in Fez.

In recent years, tourism in Morocco has become more common, bringing with it a whole new economy and also a host of problems. Clarke addresses some of the issues wrought by tourism. In the souks, many traditional handmade Moroccan goods are bought and sold, but the emerging market for tourists is leading to many changes. Clarke writes about the souk: “…I realized anew how much it was like being transported back to the Middle Ages, except that many of the goods produced are exported or sold to tourists” (68). Many goods are made to serve as mere trinkets for tourists rather than to serve their original historical purpose. Additionally, foreign nationals are buying houses in the Medina, but then modernizing them so they are converted into something quite unlike their original historical state (83). Clarke makes a valuable point, claiming that since many Moroccans cannot afford to sustain the houses they live in, those who can afford to do so (i.e. foreign nationals) should do so in keeping with the traditional style to preserve the Medina (10).

Throughout the book, Clarke provides insightful passages concerning varying aspects of Moroccan culture. From music festivals to circumcision rituals to a lively pre-Ramadan celebration, Clarke describes an assortment of traditional Moroccan customs. The Fez Festival of World Sacred Music includes performances of types of music from all around the world, culminating into a hodgepodge of Middle Eastern, Asian, Latin American, and Mediterranean culture (145). Clarke highlights the performance of a Sufi group, explaining the history behind their musical performances and describing the feeling of exaltation she, too, experienced when caught in the cacophony of frantic drum-beats and bellowing trumpets (146-147). Clarke also details a boy’s circumcision ritual, an important part of Islamic tradition, since the act of circumcision is supposed to make the boy full of baraka, or blessing.

While Clark may have indicated an understanding of Moroccan traditions in A House in Fez, she fails to fully shed her overtly westernized attitude. When detailing her visit to the electricity company, she questions their resistance to her request for four electrical lines to her house. She acknowledges that many Moroccans only use two lines as they use few appliances, but continues on to question the electricity company’s motivation behind denying her request, claiming, “…if I was paying for it what difference did it make to the electricity company?” (174). Clarke’s privileged lifestyle is painfully evident, especially when she compares hers to the lifestyle of most Moroccans living in the Medina. She also insists on forcing the workers in her home to wear protective face masks due to the health problems that can arise from breathing in dust fragments on the job site (134). The manner in which she addresses the issue is condescending. While she may be in the right for wanting the workers to wear masks, she suggests that the western way is the “right” way and that the workers don’t know any better. This comparison between the “western” way of doing things and the Moroccan way of doing this is a recurring theme throughout the book, detracting from the overarching thesis of A House in Fez– in many instances, Clarke subtly implies (ironically) that the former is superior to the latter.

Though Clarke makes valid points early on about how to preserve the Medina, she doesn’t delve deeper into these points throughout the book. Beyond a superficial paragraph about foreign nationals putting their wealth to good use by restoring and maintaining houses in the Medina, she fails to propose any other solutions to the point in question. I would have liked to learn more about conservation efforts being made either by the city or by individuals (such as Suzanna) themselves. Instead, the end of the book settled within me a sense of dissatisfaction. Clarke could have elaborated on current or future plans, but instead seemed to become complacent.

A House in Fez is an informative book about the restoration process of a riad and contains an overall satisfactory description of daily life in the Medina of Fez. However, Clarke’s ‘white savior’ complex makes it difficult to consider her book an objective read, or even a gratifying one. The lack of follow-through on her points concerning conservation of the Medina is dissatisfying, especially considering this is the main idea of the book. She doesn’t wrap up her book with commentary on the fate of the Medina or another point relevant to her thesis but rather finishes with an anecdote about a celebration of the restoration’s completion. While her presentation is engaging, Clarke’s narrative fails to strike a chord within me. A House in Fez is a sufficient read for someone looking to travel to Morocco, as it illustrates an alluring picture of life in the Medina; however, the book lacks depth for those looking to gain a deeper understanding of the problems surrounding the preservation of medieval Fez.

Clarke, Suzanna. A House in Fez: Building a Life in the Ancient Heart of Morocco. Pocket Books, 2008.

A House in Fez documents Australian writer and photographer Suzanna Clarke’s experience restoring and renovating a newly purchased home, Riad Zany, in the ancient medina of Fez, Morocco. Throughout the months spent purchasing materials, hiring craftsmen, and overseeing both the riad’s major construction and intricate details, Clarke adjusts to life outside of the home. She writes about the intricacies of Moroccan culture and her adjustment to new social circles and customs. While the bulk of her story focuses on the logistics of restoring her and partner Sandy’s newly purchased riad in Fez to its historical splendor, she takes the time to emphasize the importance of integrating Moroccan culture into her home and life, choosing to restore the home in keeping with traditional Moroccan architectural elements. Her message of preserving and appreciating Moroccan culture in Fez echoes throughout her friendships and daily life. Although Clarke’s message is admirable, her success at accurately portraying aspects of Moroccan culture is unclear, due to her perspective as an outsider and newcomer in Morocco.

Clarke’s argument to restore homes in Fez traditionally is clearly an important priority; however, her strategy of using foreign money to oversee a process unfamiliar to herself is troubling, even more so when considering the many people who many do the same. Clarke seems to view herself as a savior of sorts to Riad Zany, implying that without her and Sandy’s funding and dedication, the home would surely have fallen to ruin. This perspective struck me as somewhat Orientalist, as it is dismissive of restoration efforts within the country. She also also expresses concern for the damage done to Moroccan culture by other “expats” or foreign dwellers in Fez. However, she seems to include herself in this category only partially, and it is unclear why she excludes herself from this group.

In addition, Clarke occasionally brushes over unfamiliar elements of Moroccan culture without including local perspective on specific events. For example, while at a baby shower with friend Ayisha, Clarke describes the women as “flirting” (245) with each other through dance, but does not include any thoughts from Ayisha or the other women on the background of this tradition or how their descriptions of the dance may vary from her own. Fortunately, Clarke tends to balance out these shortcomings with passages of deep appreciation for Moroccan culture and reflections on the cultural elements in Morocco and Fez which continuously intrigue her. In fact, some of the strongest elements of the book focus on Clarke’s interactions with people in Fez. These include conversations between Clarke and workers or friends, explanations of various beliefs or traditions, and simply descriptions of the Medina itself.

Although Clarke treads on difficult cultural, political, and economic territory, she grapples with these moral dilemmas in a transparent way. She questions aloud whether her intentions in renovating the house and building a life in Fez cause more harm than good to the city, and what sort of role she should play. Clarke acknowledges her inability to fully understand the city of Fez and seeks to include local perspective on the renovations and to involve local craftspeople in order to maintain the integrity of the project. Her background is much different than the Fassi people, and it is clear that she aims to discuss this disconnect and inability to achieve perfection, rather than to ignore its presence. I appreciated this recognition, as it leaves room for conversation and improvement upon these processes in the future.

Finally, A House in Fez offers substantial background on life in Fez as well as the important history of architecture and craftsmanship used to restore the house. Much of the book focuses on the logistical aspects of buying and restoring the riad, and Clarke tells the story of each new material brought into the house- its historical origin, where she could purchase it in the medina, and what craftsmanship was necessary for its integration. This detail gives credit to the important steps in restoring traditional elements, but can sometimes become tedious to read. Many characters and small plots come into play, but many are left unresolved. I would’ve liked to see some follow-up information about some of the key characters, like Ayisha, and some of the objects that came and went from the spotlight, like the beautiful pair of doors Clarke discovers.

While A House in Fez does not offer a full picture of life in the medina of Fez, the account provides potential visitors with useful information about the city and and develops a compelling argument for home restoration in Fez, with the added disclaimer that not all such work might serve to benefit the medina. Like Clarke, I am an outsider to Moroccan culture, and don’t know the best way to go about preserving historical architecture, or any other aspects of Moroccan life. For the past two years, I have taken classes on politics, culture, and the Arabic language, but had never traveled to the region. In anticipation of coming to Morocco and spending three weeks in the Fez Medina, reading A House in Fez and considering Clarke’s perspectives helped me to reflect upon the implications of my presence, and my role within the city. I would recommend this book to anyone planning to visit Fez, or anyone with an interest in culture or architecture. Clarke provides a beautiful and intriguing description of the city, leaving plenty of room for any potential traveler to explore the Fez for themselves.

|

|

Fig 4: Khobz

Fig 4: Khobz