|

|

On my way home from the airport, I found myself staring out the car window, marveling at the rolling fields filled with tobacco; the dense forests of oak and pine with all shades of striking green; farm ponds with a thin film of algae reflecting the sun – everything Morocco doesn’t have. Yet I longed for the sparse, waterless expanse of sand and stone I had been surrounded by for the past six weeks. I couldn’t understand why for the life of me I wished for the baking heat that I cursed every day in Morocco. Upon further reflection, I realized I missed nearly everything about Morocco and that I had come to love my time spent in such a beautiful place.

Constantly, I compared the way things are in the U.S. to the way things are in Morocco, and oftentimes, concerning simple matters of daily life, I found the U.S. to come up short. Grocery stores filled with pre-made and packaged food and ‘fresh’ produce wrapped in some form of plastic can’t compare to Morocco’s open markets packed with boxes of truly fresh fruits and vegetables, racks of hanging meats likely from the slaughter that same morning, and countless varieties of nuts and dates – all locally grown. Running down to the corner café for a nus-nus isn’t an option here. I even miss nearly getting mowed over every day by a taxi driver when trying to cross the street.

Fish market in Tangier  Fresh produce in the souk But more than just material goods, I came to appreciate the tempo of life in Morocco. At first, the prospect of leisurely going about my day, not minding if I get held up for an extra hour or two, terrified me. The concept of “inshallah” as a temporal marker baffled me. By the end of my six weeks in Morocco, I quite enjoyed the rush-free attitude many Moroccans embrace. It gave me a sense of peace I don’t often experience in the hustle-and-bustle of American life.

Beyond mere lifestyle adjustments, I feel as though I learned valuable lessons in Morocco which I have yet to fully comprehend their extent. I find myself more grateful for “small” things I have which I paid no mind to before. The fact that I have air-conditioning in my house, or that I have a car, or that I have access to amazing healthcare are all aspects of my life of varying importance, yet I am grateful for each in a way I was not before. The friends I made and the families I lived with gave me the priceless knowledge that I hope to carry with me to shape the way I view my life and my privileges. I can’t express enough gratitude for the people who taught me a great deal and who made me feel at home in an unfamiliar country halfway across the world. Inshallah, one day I’ll get the chance to return.

My host family in Rabat and me

Moroccan Flag along a street in Tangier Moroccan Flag along a street in Tangier

With this blogpost, my time in the Kingdom of Morocco has come to an end. It’s been an awesome six weeks filled with adventures, intellectual and academic development. I can proudly say that this was one of the best trips of my life, if not the best. The proper organization of the Duke in the Arab World program made it possible for us to cover so much in such a short period of time. We visited all the major cities, learnt adequate Darija- the Moroccan Arabic dialect- visited several governmental, civil society and religious institutions, not forgetting the immense knowledge of the Middle East we have garnered in the Religion, Citizenship and Governance in the Modern Arab World class .

However, the trip didn’t end on the best note for me. On Friday morning, I took the train from Rabat to Casablanca with three other friends from the program and when we got to the airport, we all managed to check-in apart from one whose flight was said to have been cancelled. We chilled at the airport until 1 pm when the other two friends had to go boarding gate for their flight. When my time to leave came, I went to gate B13 where I was to board Air Maroc flight AT263 at 3:10 pm, an hour before the takeoff time. We waited there until past the boarding time but there was no sign and the staff told us to just wait. Almost two hours later, people were becoming impatient and started confronting the airline staff, some even resorted to physical confrontation and the police had to intervene. After promising that we’d be leaving in the next hour, severally (6:30, then 9, then 10) people were starting to lose hope and demanded to be told the truth, if there was a flight or they were just stalling.

Commotion at the boarding gate as passengers confront staff at the boarding desk Commotion at the boarding gate as passengers confront staff at the boarding desk

Royal Air Maroc has been having issues for the past month as a result of pilots’ strikes that has forced them to cancel close to a hundred flights since July 18th. The strike has been organized by Morocco’s Airline Pilots Association and the pilots are demanding higher wages and improved working conditions. I had an equally frustrating experience with the airline when I was leaving Nairobi in late June though it wasn’t as bad as the events of the last two days.

Twitter reaction of frustrated clients Twitter reaction of frustrated clients

At midnight, they told us that our flight has been rescheduled for 2 pm the following day and that they’d take us to a hotel where we would spend the night. One and a half hour later (we just sat there waiting for one of the staff to take us to the hotel) we arrived at Golden Tulip Farah Hotel, a five start hotel in Casablanca and one of the best in the economic capital city of Morocco. It felt so nice taking a shower and sleeping after a long and hectic day.

Golden Tulip Farah Hotel Golden Tulip Farah Hotel

At 10, we took the bus back to the airport and when the clock turned 2 pm, after a long wait, we got word that the flight has been cancelled, AGAIN. Second fight. Police intervention. Calm. One of the passengers, an Italian, showed the middle finger to a staff who was trying to calm people down, then proceeded to a make a throat-slit gesture leading to further confrontations, with some passengers siding with the now enraged Air Maroc staff, forcing him to apologize but the staff member wouldn’t accept his apology even when the guy finally agreed to. He threatened to have him arrested (he actually called the head of the airport police who took the passenger away). When the gate was finally opened a little before 4 pm, we all rejoiced. I imagined the captain in the cockpit also rejoicing for the promise of a higher pay and better working conditions. It was time for Salat to leave. He had seen everything. People applauded when the plane engines started running and so was when we touched down at N’Djamena and one last time in Nairobi. Thank you Morocco, not you Royal Air Maroc, for the amazing summer!

It feels almost surreal to be writing this final blog post. As our time in Morocco has already come to an end, I am sitting on my bed back at home feeling more of a culture shock than when I initially arrived in Morocco.

If I were to characterize my experience in Morocco, I would describe it as a roller coaster. It was an unforgettable adventure that introduced me to countless new ideas, foods, experiences, and so much more. However, at the same time, it was exhausting, at-times stressful, and a little overwhelming. That being said, I fully expected it to go that way. I knew Morocco would be stressful and overwhelming, I knew that I would learn a lot and experience dozens of new things. What I didn’t expect was that I would get so accustomed to the way of life in Morocco that I felt strange and uncomfortable being back in a comfortable place like my home.

As I am back with my daily comforts that I have grown so used to not having, I appreciate them so much more. It feels great having normal resources that before Morocco I didn’t even think twice about. I found myself asking my family: “the tap water is okay to drink right? I won’t get sick?” or even having to pause to remind myself to say thank you in my normal language – its English – come on Harry, you know that.

Either way, while these actions may seem trivial, it feels really confusing to have to remind yourself that you no longer have to think about certain aspects of your life that you constantly thought about for six weeks. Leaving home earlier today, I panicked for a minute because I didn’t have any money in my wallet for a taxi ride. Then, I came to my senses and got into my grandfather’s car to drive away. Also, all day, my family has wondered where I have been. I’ve been hidden away in my bedroom because I haven’t gotten used to the fact that no, I am no longer intruding on a stranger’s home. I’m in my own house.

So, before the Moroccan trip, every orientation and person who spoke with me warned me of the culture shock as soon as I would arrive in Morocco. I mentally prepared myself so much for it that, in the end, it was nowhere near as bad as people made it out to be. However, I had no idea how weird it would be to leave Morocco and go back to my usual life. Morocco was unbelievable and incredible. It was one of the most memorable trips I have ever been on in my life. I completely recommend anyone interested in doing this trip to bite the bullet and take the risk. However, I warn everyone to prepare to feel the “returning home” shock.

Coming back home from Morocco, everything seems outside reality. From the countless commercial businesses to the spaced out living styles of residents, I feel the familiarity of home tinged with a constant comparison of here vs. there. Six weeks in Morocco was enough for me to question everything I casually overlooked throughout the constant motions of everyday life.

For example, Morocco’s monarchy and government limited local residents from impacting the internal power structure due to the absence of elections of political figures. In a sense, locals participating within a political context wasn’t so much discouraged as it was futile in directly influencing Moroccan politics . Despite the monarchy’s inherent responsibility including the interpretation of their subjects needs, I couldn’t help but be critical of its lack of democracy. My criticisms forced me to think in terms of my own ability to participate in American politics yet my lack of active citizenship. By analyzing the constrictions of others, I realized that my previous perspective of “I alone can’t really change anything,” is not the case. Often, I’ve seen and heard (through my own experiences and documentaries) of the immigrants’ dream of coming to the US, where everything by default is better. As Americans, however, we become desensitized to our privileges and our ability to individually mold our societies to best fit our needs. Study abroad in Morocco heightened my awareness of myself as a character within the constantly changing political and social contexts.

Political talk aside, I realized I brought more than what I expected back to America: the culture and language of Morocco. Less than 24 hours in the US and I have had to fight the internal impulse to respond in Moroccan Arabic numerous times. Personally, the phrase Inshallah –meaning “if God wills it” – will be a permanent addition to my vocabulary. Its meaning extending across serious and casual situations. Its versatile nature has captured the hearts of me and my classmates alike. For instance, Inshallah I will get the internship I applied for the Fall semester. Inshallah, I will go to class to today. Inshallah, this blog post won’t be late. This term has taught me that not everything may be possible and that you shouldn’t dwell on it. The laid back Moroccan culture has encouraged me to distance myself from stressful environments and take things at my own pace.

This enitre cultural immersion has forced me to re-interpret myself. In the process, I have come to new realizations about the world around me and a new way of understanding others within their own societies. My time in Morocco was as beautiful as it was educational in both the formal classroom setting and the informal backdrop of the bustling cities.

It’s 3:30 AM and I’m finally settled in before my flight home. Today has certainly been intense, but in retrospect, it’s really just the same level of intensity as any other day over the past 6 weeks. My entire trip felt like a whirlwind from start to finish, and looking back, the days seem to blend together. But there are certainly specific memories that stand out. There was the time I rode a camel in the Sahara Desert; there was the time I went to a beautiful 17th century synagogue in Fez; there was the time a sheep was slaughtered a few feet away from my bedroom. While I will never forget any of those (especially the sheep slaughter and all of the other festivities for the baby welcoming), the most important memories are actually the ones that blend together, the ones we forget about. I can’t speak to most people’s memories, but mine works in a way where I only memorize the things that stand out to me; I remember very little about my typical daily experience. But those experiences are the most important because those are the ones that make up most our lives. Your special experiences shape your life, but your routine is your life. Morocco will always be one of those special experiences that shape my life, but at the same time, it was merely a microcosm of the routine that is my life. At the end of the day, all that means is that my time in Morocco will forever be part of me.

As an important time in my life, I wanted to reflect on what I learned from it that I will take forward in my life. Because I have learned a lot in Morocco, but only some of it has an impact moving forward.

- I learned the Arabic alphabet, which will be essential to any future Arabic studies

- I have reconsidered my definition of citizenship and how I view my role in the world

- I now fully understand the concept of civil society and its importance in my life

- I have reconsidered my relationship with Judaism

- I have learned about multiple opportunities that I could pursue in the future.

Overall, I have learned so much in Morocco, and there’s plenty more that I haven’t even considered. I am so happy that I took this trip; I had to leave because my time there was over, but the country will always have a special place in my heart.

With this blogpost, our time in Morocco comes to an end. This finality snuck up on me– as much as I missed my family and American food, I’d grown accustomed to everything Morocco was. It’s laissez-faire culture of “Insha’allah” (God-willing), and “msh mshkila” (no problem) have been ingrained in me. It’s not very efficient: there is a lack of accountability within government and many pressing matters to resolve, but people live a peaceful, relaxed life. As a person with anxiety, this was an amazing culture shock. Gone were hard, pressing deadlines, as this program was designed for you to actually fully immerse in Morocco. There was a lot of work to do, but the program was structured so that you immersed as you worked. With this blogpost, our time in Morocco comes to an end. This finality snuck up on me– as much as I missed my family and American food, I’d grown accustomed to everything Morocco was. It’s laissez-faire culture of “Insha’allah” (God-willing), and “msh mshkila” (no problem) have been ingrained in me. It’s not very efficient: there is a lack of accountability within government and many pressing matters to resolve, but people live a peaceful, relaxed life. As a person with anxiety, this was an amazing culture shock. Gone were hard, pressing deadlines, as this program was designed for you to actually fully immerse in Morocco. There was a lot of work to do, but the program was structured so that you immersed as you worked.

I’ll never forget the kindness of my host families. I’d never felt such warmth and welcome from someone who was a stranger to me at first. I enjoyed having dinner with my homestay family every night, learning Arabic from them, and seeing their interactions.

One of my favorite activities was to walk around and explore. Walking (semi)aimlessly is one of the best activities I would recommend to anyone visiting Morocco. That’s how you see how people live. I remember seeing little boys playing soccer on one of my excursions, and a lot of people waiting for big taxis on another. It’s the little things like that. Walking around is also one of the best ways to practice and learn Arabic. You force yourself to have to ask for directions in Arabic, and most verbal exchanges also happen in Arabic. It’s true learning.

- I’m extremely grateful for everything Morocco was to me. I want to thank my group for sharing their stories and this part of their lives on this trip. This has truly been an amazing experience.

After seven weeks abroad, it is my first night back in the United States. It feels different to be back in my home country, almost surreal, but also not so different from my nights in Morocco; I’m still laughing with my best friend Molly, still exhausted from a long day, still cranking out homework. As I reflect on my trip with friends and family from home, there is almost too much to process, too many wonderful memories and new experiences to retell in a single night. But, at the same time, my journey was not without its flaws. I will miss seeing cats snoozing on the sidewalks as I walk to school, but I will not miss the catcalls I received on those same walks. I will miss hearing the beautiful calls to prayer, but I will not miss the pressure I felt to wear long pants and skirts every day (see: the catcalling). I will miss having sunny day after sunny day, but not high temperatures of 110 (see: the long pants and skirts). And I will miss my loving Moroccan host families and the hospitality they showed me when I was so far from home, but I am also eager to see my American family after so much time apart.

I am not sure if I will ever return to Morocco, mostly because there are so many other countries I want to visit, countries I have never traveled to. Even so, I feel that I have been treated to a good survey of the country, hitting most of the major cities and interacting with countless locals as I practiced my Darija. I feel that I have observed the best of what Morocco has to offer and, also, as I mentioned, some of the flaws of Moroccan society (again, see: the catcalling). But it has reminded me that every society has its imperfections, and I have garnered new observations and new perspectives to take with me as I travel to different countries and compare and contrast different cultures.

Me at the graduation ceremony at Qalam wa Lawh – my last full day in Morocco.

My first blog post this trip was about sitting on the train to the Casablanca airport, completely losing my mind, wondering how I could possibly live for six entire weeks in this unfamiliar place where I had spent my first full day feeling pretty generally overwhelmed.

This morning I once again sat on the train to the Casablanca airport, and I am pleased to report that in the six weeks between, for all intents and purposes, I’ve been perfectly fine.

It’s been a pretty crazy six weeks, with new challenges popping up each time we had begun to feel comfortable with our current situations.

We spent three weeks in Fez, where we learned to navigate the taxi system and the winding roads of the old medina. We got to know our host families, even with somewhat of a language barrier. After three weeks, routine had set in. Get up, taxi to school, take our daily classes, perhaps embark upon a minor after school adventure like visiting the Fez gardens or ordering a four-cheese pizza at our favorite café (hold the rocks, please), go home for snack with our host families followed by homework and dinner at a time most would call a midnight snack. And all again the next day. This routine set in and suddenly it was time to go to Rabat.

A new city, a new host family, a new roommate for me and Bailey, a new school, and a new friendly school cat, Rabat was a new face of Morocco. While we were pretty sure that our homestay was actually just an AirB&B, Rabat felt like home in many ways. I enjoyed going for runs in the old city, walking along the beach, and trying out new restaurants near Qalam.

Besides falling into daily life within Fez and Rabat, the most wonderful part of the trip was adventuring around all of Morocco’s beautiful cities and sights. Marrakech, Merzouga, Tangier, Meknes, and Casablanca showed different sides of Morocco and offered a welcome break from the classes of the week to explore the country. More than just sightseeing, being in Morocco for six weeks was a glimpse into a style of life so much different than my own in the United States. I loved Morocco because I could be slightly late everywhere I went, because I learned to feel comfortable in a place initially so uncomfortable to me, and because of each surreal moment that made me feel so grateful to be exploring somewhere new with some of the coolest people around.

Here’s hoping to an eventual return to Morocco! Bislamah!

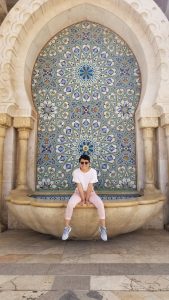

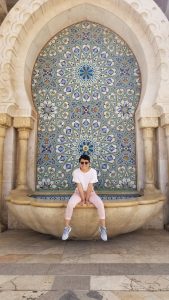

Bailey and me at the Hassan II mosque in Casablaca for the second time, feeling much more relaxed

Thomas the Train Stomach: knotted. Skin: dried out and a little burnt. Body: dehydrated. A few days ago, it felt like I only had two short-circuited synapses left in my brain. Like Thomas the Train, it was time for me to leave.

I’m still ready to go, but after a bittersweet (think mint-that’s-been-left-too-long-in-the-tea kind of bittersweet) graduation and a laidback evening, I also feel more refreshed, not to mention more emotional. Murphy’s Law contributes a little bit to these feelings: my flight is delayed until tomorrow at 7 AM. Another flight has been extremely delayed as well, and as I type this, I can hear a man’s voice barking at a Royal Air Maroc representative. I’m grateful that I’m not in that cramped office.

Fortunately, my extra time in the airport has introduced me to plenty of nice, unfrazzled people as well. There was the family from New York (two kids, the mom is from Morocco, the dad is a wedding entertainer) who reassured me everything would work out when they heard my flight was cancelled. Afterwards, one of the Royal Air Maroc agents printed my boarding pass without making me wait too long in line. Another passenger shared her table with me. More recently, I had a ten-minute conversation with a Kenyan woman who is also stuck here for the night. It was her first time in Morocco too. On some pseudo-intellectual level, my station at one of the four charging outlets in Casablanca Airport attracts so many different people that it reminds me of the old trade routes around the Arab Gulf. I suppose the frameworks of Tribal Modern can cross an entire continent.

I still feel some residual helplessness and panic after waiting more than an hour in four different lines. I have places to be! I have things to do! America is calling! My airport sleepover feels simultaneously fine and scary. At least the wifi here can numb any feelings of isolation – I’m a true millennial after all. Similar to many other things in Morocco, I have little control over this situation, so I have to accept my reality. Things will happen here, inshallah, God willing. If – or when – they don’t happen, that’s okay too, inshallah.

On some level, I bought into this mentality a little too well on this trip. My meals, my taxi drivers, my excursions, and almost everything else were always out of my control, so at times it felt like I had no control over anything, including my reactions. As I had to practice patience and visualizing my happy place today (it’s a silly, but effective technique), it felt empowering to realize that my philosophy of relinquishing control was flawed. There is more balance to the control/no-control dichotomy than I realized.

Dealing with the unexpected has been just as fun and exciting as it has felt defeating. Salat, Bailey, Molly, and I managed to hop on an early train to Casablanca because we were flexible. I took advantage of our less structured time in Tangier, so I poked around the Caves of Hercules. I still remember my delight when we accidentally discovered little tide pools outside of Rabat. These memories don’t change that I’m stranded in an airport across the Atlantic, but they certainly help.

I’ve got places to go, hard airport floors to sleep on, and even more unexpected, crazy adventures in the future. So… Yallah!

Took a Train to Morocco  My Band-Aid Repaired, Cracked Screen Phone aka My Untrustworthy Companion

I opened the door of the canary yellow cab and slid onto the sunbaked leather seat that was half unhinged from the floorboard. The driver gave me an almost-toothless smile with only a few rotted nubs remaining in his otherwise vacant mouth. The old engine shook the rickety car as we tumbled down the busy street. A breeze blew in through the half-cracked window while we careened our way over craggy hills and deserted valleys on a crumbling road. But suddenly, I found myself back into the midst of civilization with towering apartment complexes and hotel resorts whose grass looked meticulously maintained. Wrought iron gates lined the streets filled with cars and taxicabs and bustling tourists enjoying the late-day sun. The driver screeched to a halt and I fished in my pocket to find the proper payment. The back of my shirt was stuck to the chair with sweat, but I managed to pull myself off and exit the cab. A sign pointed me to my destination and I followed it down a hill. I was met with waves crashing against weathered rocks and an infinite view of the sea, not able to tell where it ended and the horizon began. I took a deep breath in, smelling the salty air. I walked down well-groomed stairs into the mouth of a giant cave. They call it the Cave of Hercules because he supposedly rested there during his trials. Believing the myth or not, I passed by lines of merchants and went deeper into the cave. There I saw the main attraction: a window to the sea in the shape of the African continent. I will admit, I saw the resemblance, and so did the hundreds of tour groups and school children. But looking past that hole out into the sea, for one of the first times on my trip, I thought about what was on the other side of that endless ocean: home.

I have never felt more American then when coming to Morocco. It was a strange twist of fate for me. I had planned to try to assimilate with Moroccans and shed my American heritage for six weeks. However, I quickly realized that no matter what I did, I would never be considered to be a local. So why hide it? Why pretend to be a European or someone else? I have grasped that when coming to another country, you are an ambassador for your people and your culture. I came to understand that I am American, and that it is something of which I should be proud. The world is an increasingly more interconnected forum. However, for some people, their only interactions with foreign cultures and peoples is through the Internet. This creates a biased view in their minds about who these people are. So, when I am given the chance to talk to people, I embrace that I am an American and that I can make a difference in the way that our country is perceived by the world. I have a deeper understanding after being in Morocco for six weeks about what it truly means to be a global citizen. I better appreciate the role that I play, whether I intend to or not. The actions that we take have global impact. What I post online can reach people thousands of miles away— people whom I had not even intended to reach. When I looked out of that sea window into the ocean, I thought about home because I know that I missed it. Morocco has been an eye-opening experience into a culture so removed from my own. People say that America has no culture, but I disagree. There is something that makes America unique, something intangible, but most definitely felt. In coming back to the United States, I feel at ease but a twinge of sadness. I am excited to go back to something familiar, but I want to keep exploring and learning about the world. But, perhaps that is an adventure for another time.

Sunset in Tangier  View from a Tangier rooftop  Cave of Hercules

It was at least 100 degrees Fahrenheit. As I dredged through the midday sun, I was sure Marrakesh was on a mission to have my last brain cell leak through my ears. Heat was radiating off the merciless concrete as we inched forward through a small local neighborhood. Finally arriving within a small parking lot, I gazed up at our destination (an education center), and hoped my battle-hardened thread of sanity didn’t snap before their door opened. After we ascended the flights of stairs leading to the building’s entrance, comfortable couches and blissfully chilled juice marked the end of our journey through the concrete Sahara.

Sprawled across numerous couches, we were caught dazed in a heat induced stupor. Before the droplets of sweat accumulating on my forehead could drip down, representatives of varying NGOs filed into the sweltering room. Particularly, one organization captivated my attention and introduced me to an entire population of Moroccan residents shunned by society and government alike: the illegal children from single-mothers born outside the institution of marriage. These children are not recognized by the country nor are their fathers required by the government to provide any financial help. The identity of the father is often unknown, with single-mothers being pressured to keep this information hidden as her situation is considered shameful among the public.

Within Marrakesh, Les Enfants de L’Atlas is an orphanage that receives illegally born children from the only courthouse within the city. Their representatives showed actual interest and amazed me as they shared their goals and ongoing projects to increase the quality of life of their children. Upon the conclusion of their presentation, they invited a group of students to visit their site and observe their plans actualized into projects pending completion. Immediately, I was overwhelmingly eager to interact with their children and simultaneously irresolute in the impact of this action and its consequences. Who am I, a student leaving the city the following day, to gawk at a group of children deprived of a traditional family? I refused to have them feel as though they were a live petting zoo meant to appease potential donors. Morally, my decision was fixed in a limbo between potentially impacting the orphanage’s residents on a spectrum of negative and positive outcomes.

As cooler temperatures dominated my surroundings, they were accompanied by the setting sun’s waning, yet relentless, supervision. That night’s edition of “Late Night Thoughts to Chew On” starred a frequent guest named Indecisiveness. Although Indecisiveness does tend to entertain the audience till morning, they also prevent other thoughts to take shape. In the end, I decided to join the visiting group. The opportunity of making a difference for even a single child outweighed the uncertain outcome of such a visit.

Upon arriving, the orphanage immediately surprised me with how importantly the staff and caretakers conducted their activities among the children. Houses were meticulously clean, kitchens with granite countertops, men and women vigilantly overseeing playful children scattered underneath the cool shade. Unfortunately, the older children were on a field-trip to a local farm, but I was glad I came.

Although the visit had questionable outcomes, seeing as the children who were there are unlikely to remember the experience, my intentions were to do the most I could during the short period of time I had with them. In the end, doing the best we can with what we have is the only thing one can do. I saw this in the orphanage (as an organization) with ambitious goals, the caretakers in their attempts to create a unique familial community, and among the children as they squirmed about simply enjoying the plentiful company. Despite much needed reform on fundamental issues surrounding the need for such an orphanage, the organization was attempting to do the most with their situation.

The logo of the High Atlas Foundation (HAF), an NGO I found out about in Marrakesh, Morocco

Founded in 1062 north of the Atlas Mountains (specifically the High Atlas range), Marrakesh is one of the four former imperial cities and is now known as the tourist capital of Morocco; having been visited by more than 2 million people in 2017 alone, it’s hard to disagree with this title. However, I personally didn’t care for Marrakesh from a touristic perspective. I’ve already spent four weeks in Morocco, so I’ve spent enough time here being a tourist. Instead, I wanted to come to Marrakesh to learn – the reason I came to Morocco in the first place. But I wasn’t taking classes there; I was learning from experience.

In Marrakesh, we learned about several different institutions that are considered part of civil society, the buffer zone between home and government where citizens participate in political life. I later visited an orphanage near the city, but the institution that stood out most to me from a conceptual standpoint was the High Atlas Foundation (HAF). Founded in 2000 by former Peace Corps volunteers, HAF functions as a third-party actor to help communities in Morocco grow and develop, eventually self-sustainably. HAF goes to communities in Morocco that want their assistance and participate in any project that the community decides to pursue, but their largest initiative is the 1 Billion Tree Campaign. Fruit trees are incredibly profitable; just 100 trees (which is pretty small in terms of nursery size) would more than double an agricultural family’s annual income. The High Atlas Foundation is pushing this campaign in order to bring an end to subsistence agriculture and actually create sustainable profit in the country. For example, almonds are only grown in six countries – Morocco is one of them; the expansion of almond production is critical because wheat and barley are the two most grown products, but almonds are far more valuable per metric ton (20x more than wheat and 30x more than barley). Almond trees are just one of many endemic tree types HAF hopes to plant across Morocco in the coming years. Currently, the High Atlas Foundation has only grown 3.5 million trees out of its goal of 1 billion, but it grew 1.4 million in 2017 alone and these numbers will continue to grow – especially as HAF gains access to more land.

I had the opportunity to interview the president of the foundation, Yossef Ben-Meir, over Skype. We met briefly in Marrakesh when he gave a presentation about the organization to me and my peers. I decided to reach out to him to learn more about the organization, but also more about him. He himself is not Moroccan, so I was interested in how he ended up spending most of the past 25 years in Morocco.

Born in the United States, Ben-Meir was the child of Iraqi Jews. Jewish people have a significant history in the region that is now Iraq, having been present since the time of Babylonia. However, most of the population immigrated to Israel following its independence. Ben-Meir’s parents later immigrated from Israel to the United States, and he was born thereafter. Yossef Ben-Meir grew up in America, but upon graduating from college, he decided to volunteer for the Peace Corps and was stationed in Morocco. While in Morocco, he experienced its beautiful culture but also saw many places that suffered from a lack of clean water and proper healthcare; these sights are what first inspired Ben-Meir to found HAF, but that wouldn’t happen until years later.

After serving in Morocco, he returned to the US and got a graduate degree from Clark University. Within a week, though, he took a one-way flight to Morocco and became an associate director of the Peace Corps in Morocco. While serving as associate director, he learned managerial and organizational skills that would be invaluable for his work with the foundation. After working for a few years, Ben-Meir returned to the US to study one last time. He began working on a Ph.D. in the Fletcher School at Tufts, but he was struck by an illness that left him mostly bed-ridden for a year in New Mexico. Not sure what the future held for him, it was at this point in time that Yossef finally pushed for his dream to become a reality; he contacted other former Peace Corps volunteers, and the High Atlas Foundation was founded soon after. In New Mexico, he also discovered sociology and got a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of New Mexico; these years were especially important and formative for Ben-Meir as his studies in sociology have shaped his worldview and the way he operates HAF. Once he earned his Ph.D., Yossef Ben-Meir returned to Morocco, where he remains today. From 2009-2010, he was a professor at the American-funded Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane while serving on the board of the High Atlas Foundation; since 2010, though, HAF needed more direct attention, so Ben-Meir took over as President of Operations and has been in this full-time role since.

Today, the High Atlas Foundation, despite its regional name, actually serves in all 12 regions of Morocco, including the Western Sahara. The institution is undertaking approximately 50 projects across Morocco (a staggering number considering the NGO has only 25 employees), but it’s a feasible operation because its organizational structure relies on members of the participating communities doing the vast majority of the work while HAF helps facilitates these actions economically and legally. Of its 50 projects, most revolve around the 1 Billion Tree Campaign, but one particular project concerns interfaith relations as well.

Formed in 2012, the House of Life project is the crux of the intersection of sustainable prosperity and cultural preservation. In Al Haouz Province, a rural area outside of Marrakesh, a new nursery was started at the site of the 700-year-old tomb of healer Rabbi Raphael Hacohen. 120,000 seeds of various trees were planted, and they are currently being maintained by 1,000 farmers and 130 schools. By allowing for this Jewish land to be used to help support the lives of many Moroccan Muslims, a critical dynamic of Morocco is made clear: Jewish history/culture is an accepted and appreciated part of the greater Moroccan history/culture. As Ben-Meir himself said, “Jewish culture is in the fabric of the people of Morocco.” This project is critical not just for the importance and optics of interfaith relations but also for major practical implications. The Moroccan government has less than 1,500 parcels of land available and suitable for the cultivation of fruit trees (the Department of Rural Development, Water, and Forests has 700 parcels of land available, the Department of Agriculture has 300, and a few hundred parcels are available across all other departments). Meanwhile, the Jewish community of Morocco has 600 parcels of land available that adjoin Jewish cemeteries across the nation. That vast amount of land would have incredible importance in the High Atlas Foundation achieving its goal of 1 billion fruit trees in Morocco. Not only does that have economic significance, it also has personal significance for Yossef Ben-Meir. Discussing our respective Jewish identities, I told him about the importance of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to me. Ben-Meir also agreed about the vital importance of this issue to the Israeli and Palestinian people, the region around them, and the world. “Its consequences are global and must be solved for the sake of everyone, especially the parties as it is destroying both societies.” However, he also told me that there are so many other ways to improve the world concerning one’s Jewish values. For him, “There is nothing more important that I can do as a Jewish person in my position for Muslim-Jewish relations and Jewish life in Morocco than making use of [those 600 parcels of land].” Though I’ve only known him for a short time, Ben-Meir has already taught me to reconsider how I view my Jewish values and how I intend to use them to help make the world a better place. And this lesson isn’t meant just for me: anyone can shape the world in a large number of ways using their identities, and there are many ways to do this that aren’t explicitly rooted within one’s identity.

So as Yossef Ben-Meir continues to help Morocco in a way that aligns with his identity, I’ll also use my identity to help me change the world. Though I’m not sure how I will do this, I fully intend to use my subjective values in order to objectively improve the world around me.

|

|

Moroccan Flag along a street in Tangier

Moroccan Flag along a street in Tangier

Commotion at the boarding gate as passengers confront staff at the boarding desk

Commotion at the boarding gate as passengers confront staff at the boarding desk Twitter reaction of frustrated clients

Twitter reaction of frustrated clients

Golden Tulip Farah Hotel

Golden Tulip Farah Hotel

With this blogpost, our time in Morocco comes to an end. This finality snuck up on me– as much as I missed my family and American food, I’d grown accustomed to everything Morocco was. It’s laissez-faire culture of “Insha’allah” (God-willing), and “msh mshkila” (no problem) have been ingrained in me. It’s not very efficient: there is a lack of accountability within government and many pressing matters to resolve, but people live a peaceful, relaxed life. As a person with anxiety, this was an amazing culture shock. Gone were hard, pressing deadlines, as this program was designed for you to actually fully immerse in Morocco. There was a lot of work to do, but the program was structured so that you immersed as you worked.

With this blogpost, our time in Morocco comes to an end. This finality snuck up on me– as much as I missed my family and American food, I’d grown accustomed to everything Morocco was. It’s laissez-faire culture of “Insha’allah” (God-willing), and “msh mshkila” (no problem) have been ingrained in me. It’s not very efficient: there is a lack of accountability within government and many pressing matters to resolve, but people live a peaceful, relaxed life. As a person with anxiety, this was an amazing culture shock. Gone were hard, pressing deadlines, as this program was designed for you to actually fully immerse in Morocco. There was a lot of work to do, but the program was structured so that you immersed as you worked.