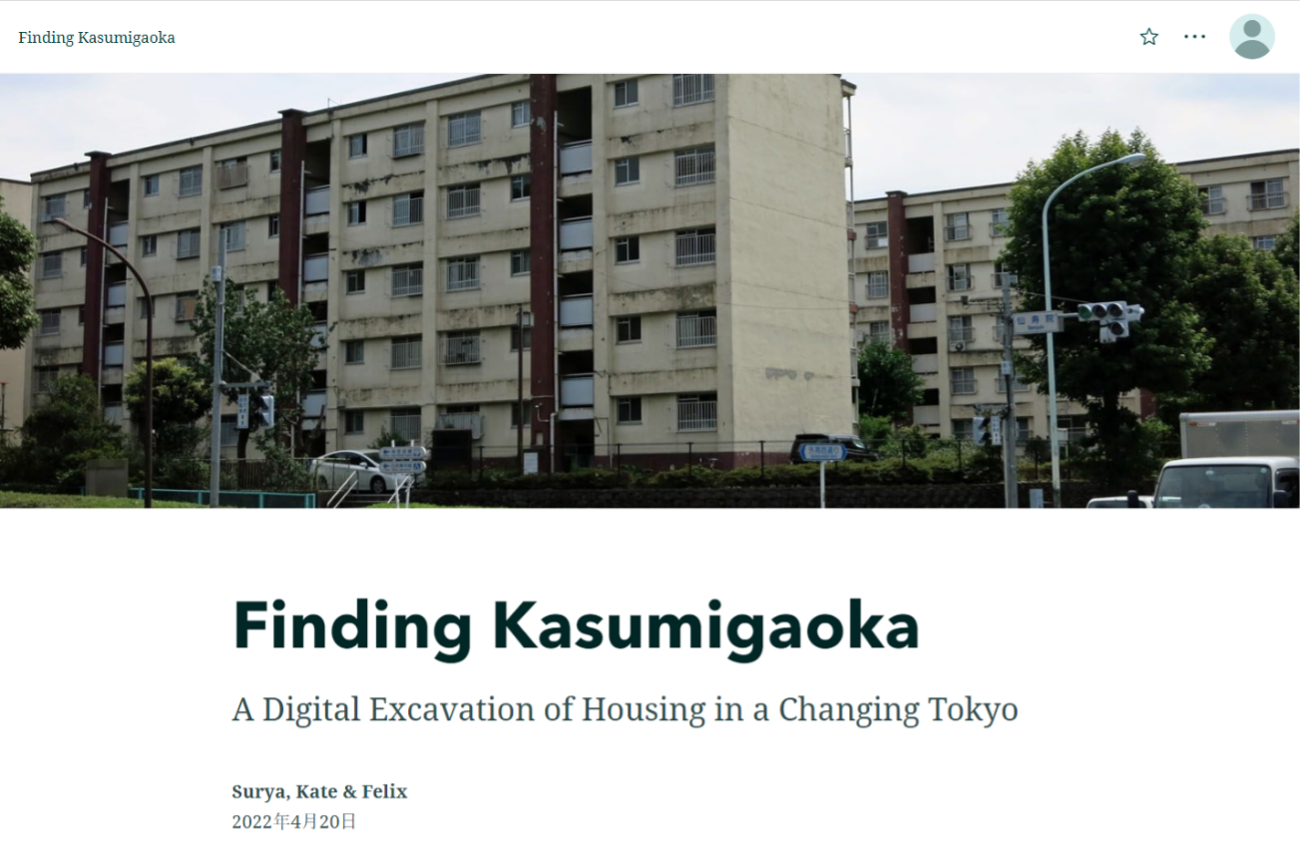

The work of this semester took many of the ideas that Team Tokyo discussed last semester, and formed them into tangible work. Specifically, I collaborated with Felix, Surya, and Professor Wendell to visualize the Kasumigaoka Apartment Complexes and the movement of two individuals who once resided in the now destroyed apartments.

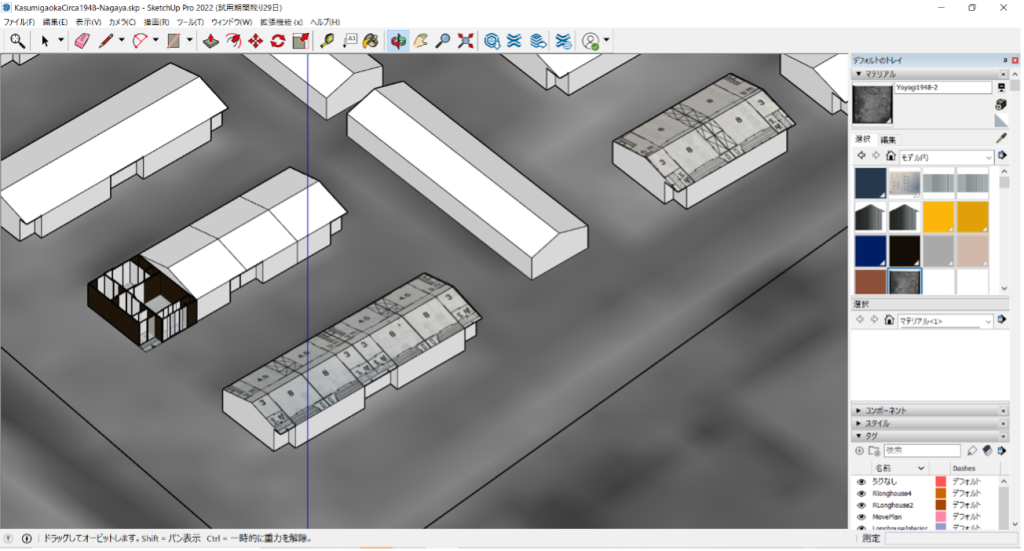

We used many forms of media to investigate the history of Kasumigaoka. WIth the help of Matthew, we were able to track the change of Kasumigaoka and the surrounding area in Tokyo over time. Aerial maps taken from the 1920s all the way to present day were essential to our understanding of how the Olympics shaped the infrastructure and housing of Tokyo in the area. Through these aerial maps, we were able to see the construction and destruction of Kasumigaoka. We also utilized photographs and housing plans of the apartment complex to build a 3D model of the housing units using Sketch-Up. Sketch-Up–which Professor Wendell taught us how to navigate–allowed us to create something viewers could interface with and use to get a more complete understanding of the apartment complex.

Finally, we relied on interviews and other literature to chart the movement of displaced individuals who once lived in Kasumigaoka. We focused on the case studies of “J-san” and “S-san,” individuals who had given multiple interviews about their movement throughout their life and experience being evicted by the Japanese government. These stories were very powerful and distressing at times, and speak to the ways in which the Olympics does not always benefit a city and its people. J-san, born in 1933, moved early throughout their life because of the war. In between when they were born and then they moved to Kasumigaoka with their parents in 1965, J-san lived in Minobu, Fukushima, and various other locations in Tokyo. They stayed in Kasumigaoka for the longest period of time, living there until the Japanese government evicted them in 2013. The land, which is near the Japanese National Stadium and other buildings constructed for the Olympics, was taken to accommodate more Olympic infrastructure. Similarly, S-San was born in Fukugawa and then shortly after moved to Dailan, Manchuria for her father’s work on the Manchurian Railway Company. Following Japan’s defeat in WWII, S-san’s family was repatriated to Japan, where they bounced around to different cities until settling in Kasumigaoka in 1951. Similarly to J-san’s story, S-san lived in Kasumigaoka until being evicted and relocated to the Jingumae Apartments. All of this work can be viewed using this link and clicking the “view story” button.

What I enjoyed most about this semester was the use of many different forms of media and archives. Most of my work at Duke previously relied on literature, written academic sources, and only occasional photographs or videos. It was a really unique learning experience to explore the topic of displacement in relation to the Olympics through old maps, photographs, and 3D models. I am grateful to have learned something new about Tokyo and the Olympics and even more grateful to have worked with such a wonderful team! Even as I graduate this year, I am excited to see how the lab continues to explore cities in the coming year!