In the last few years, investors have poured billions of dollars into a diverse array of digital innovations. One area is “the metaverse” – virtual worlds that users can interact with through “avatars”. Another area is cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (DeFi), which aim to build new forms of money and financial services based on distributed ledger technologies (DLT). Even grander are new proposals for a decentralized internet (“Web 3.0”) where users take control over their data. These proposals envisage a new “creator economy”, empowering artists with greater control over the fruits of their labor.

What do these various initiatives have in common? For one, each has been described in some form in the work of author Neal Stephenson. Stephenson’s 1992 book Snow Crash is credited with introducing the term metaverse (from Greek “meta” – “beyond” – and “universe”). Cryptonomicon (1999) is considered by some to have popularized the idea of cryptocurrencies. And The Diamond Age (1995) already discusses a decentralized internet. Media scholar Lana Swartz notes how crypto aficionados explicitly refer to Stephenson’s books as inspiration. According to one leader in the Bitcoin community, “Neal Stephenson is more of a prophet than a novelist. He had figured it all out”.

Since Stephenson has correctly foreseen many recent developments, what else can be learned from his fiction for current debates on crypto and Web3? This essay provides five insights.

- Dystopias make for a strange choice of blueprints

Stephenson’s Snow Crash is set in the near future in (what is left of) the United States. The country has fallen apart into small, independent polities (“franchises”) full of lawless but well-armed individuals. Everything has been privatized – down to highways, police forces, the courts and even the CIA. The economy has collapsed amid hyperinflation and different franchises have their own currencies. The book’s protagonist, Hiro, lives in a storage unit, which may or may not be contaminated by radioactive waste.

The one piece of truly global infrastructure is the metaverse, run by the private Global Multimedia Protocol Group. Access to this world is highly stratified. High-income users have high-quality avatars and see the world in high-definition streaming, while others are relegated to a grainy black and white.

As Meta and Microsoft announced their big bets on virtual reality technology, Stephenson’s metaverse dystopia is a strange blueprint. On the other hand, it may make sense as an investment opportunity – if your firm aspires to be the monopolist.

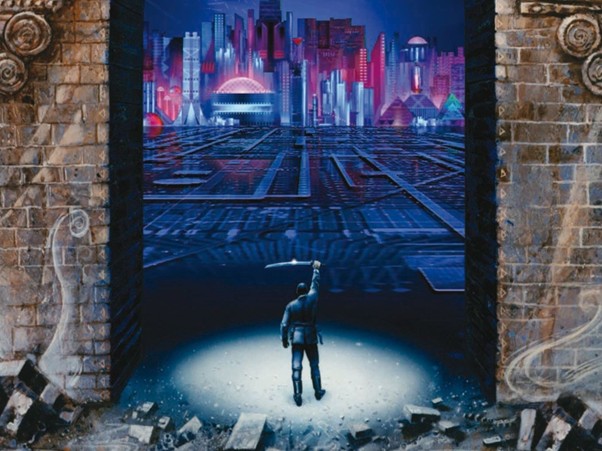

Hardly a cheerful world – Hiro Protagonist brandishes his saber toward “the street” on the cover of Stephenson’s 1992 Snow Crash.

- It’s never just the technology – it’s what people do with it

In Snow Crash, the metaverse only takes off when avatars can mimic human facial expressions and emotions. Personalized, intuitive interfaces allow the technology to be widely adopted. (This innovation comes from a female developer, Juanita, who was initially marginalized by her male colleagues.)

This has parallels in the real world. Steve Jobs took a calligraphy course at Reed College in the 1970s – and this became an inspiration to the fonts later introduced in Apple computers. The internet achieved mass global adoption when it became possible for users to post content (what we now know as “Web 2.0”). And it is social dynamics like distrust of institutions, fear of missing out and speculation that fueled the recent rise of crypto and Web3.

More generally, Stephenson’s work combines insights from computer science, mathematics, linguistics, archaeology, and religion – from Sumerian mythology to nuclear physics. In a time in which tech companies are encouraged to hire anthropologists and interdisciplinary collaboration is in high demand, works of fiction show that hard sciences and social sciences can be fruitfully combined.

- People want stable currencies

In Cryptonomicon, the main characters use “digital currency” to transfer funds from one country to another. These include earnings from new digital networks for Filipino families to share messages across borders, and of finding gold in a sunken submarine. They note the opportunity for people in countries with high inflation and capital controls, as in East Asia after the Asian debt crisis. Interestingly, this digital currency is backed by gold. In this sense, it is more of a stablecoin than a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin.

Meanwhile, in The Diamond Age nation-states have broken down and been replaced by different communities (“phyles”) bound by ethnic kinship and culture. The collapse of nation-states came from a decentralized internet, “built from the ground up to provide privacy… [and to] transfer money”. It brought down tax systems, because financial transactions could no longer be monitored. Yet even in this chaotic world, people want stable currencies, and exchange “universal currency units” across phyles.

- Be careful not to fall in with thieves

A recurring theme in Stephenson’s work is the illicit use of technology. In Snow Crash, the mafia has taken over the surprisingly high-tech world of pizza delivery. In Cryptonomicon, the “data haven” set up in the fictional Sultanate of Kunakata is quickly overrun with high-profile drug dealers and mercenaries – who are naturally attracted to assurances of unrestricted privacy. The main characters realize that in supporting the project (in their case for nobler goals), they have “fallen in with thieves”.

In the real world pseudo-anonymous blockchains have gained popularity with criminals – from Silk Road in the early days to various “privacy coins” more recently. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have been pinpointed as a channel for money laundering and terrorism financing. Yet the technology also offers resources to authorities, as with blockchain analytics companies that gauge financial crime risks.

- Beware the rogue billionaires

Stephenson’s characters shape society in sometimes profound ways. In Snow Crash, billionaire L. Bob Rife controls the networks on which information flows. Among other things, he uses this to support a coup and manipulate millions into doing his bidding. In Termination Shock (2021), a Texas billionaire geo-engineers the earth’s climate by shooting Sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere. Again, private initiative takes a role that may otherwise fall to national governments – yet without the accountability that governments offer.

This echoes recent debates on the role of billionaires in societal initiatives. Private firms are pushing the frontier in space exploration, taking over what was previously done by NASA. Facebook (Meta) has been described as “more like a government than a traditional company”. The now-defunct Libra project had ideals about becoming “a simple global currency… [for] billions of people” – taking over a role played by national central banks and international financial institutions. Yet unlike public sector institutions, which have legal mandates to foster financial and price stability accountable to society, Libra would have been accountable only to its private sector members.

Conclusion

Neal Stephenson’s work has been an inspiration to the development of crypto and web3. It is a case of how, sometimes, life imitates art.

Yet in the fictional worlds that inspired real innovations, there are striking lessons. Heeding those may help real-world incarnations turn out better than the stories that they came from.

Fabian Dior and David Winter are research economists. The views expressed here are solely their own.

Fascinating read! It’s wild how much Stephenson envisioned, his worlds are full of wisdom for today’s innovators. Really amazing dear.