Open AI is an artificial intelligence (AI) research and deployment company that is behind the creation and commercialization of ChatGPT as well as other research initiatives concerning artificial general intelligence (AGI), “a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work.” AGI has been considered a fringe topic in the technology industry. For example, during a talk at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2014, Elon Musk said: “[w]ith artificial intelligence we are summoning the demon.” However, AI has been part of the global ideation for a long time. Thus, the fact that OpenAI decided to make ChatGPT available to the broader public was revolutionary.

The intriguing chain of events regarding the firing and subsequent rehiring of Open AI’s CEO, Sam Altman, at the end of 2023 and safety and transparency issues, including a tussle with Scarlett Johansson over the use of her voice for a new AI product, have raised even more questions about governing AI in the boardroom and whether such a chain of events is, in fact, a sign that governing AI is a challenging task that is impossible to achieve without a high level of hindsight. For example, referring to the end of 2023 events, Jared Ellias, Scott C. Collins Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, asked in a Tweet: “Is it possible the @OpenAI thing makes no sense because this board was sent from the future to fire Sam Altman and save humanity?”

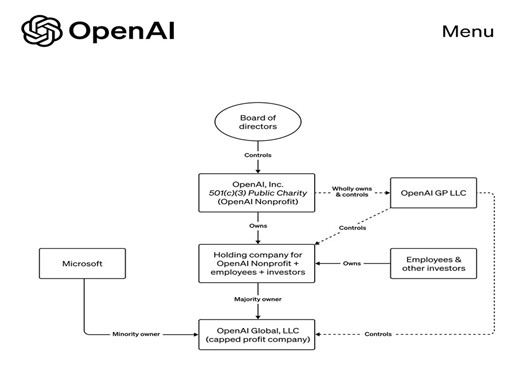

Open AI’s mission is clear: “to ensure that artificial general intelligence—AI systems that are generally smarter than humans—benefits all of humanity.” To fulfill this mission, Open AI is governed by a board of directors that manages Open AI, Inc., a non-profit organization operating under Internal Revenue Code §501(c)(3) as a public charity (Open AI Nonprofit). Pursuant to Open AI’s website, the board is composed of independent directors who do not hold equity in OpenAi, including its CEO, Sam Altman. They make rather difficult decisions with sweeping ramifications for society and humanity, such as when AGI is achieved. Open AI’s ownership structure is below.

Despite calls for safety testing and consumer protection, considering fast developments in AI technology (Google has recently created a new A.I. system called Gemini Ultra), there is a clear absence of applicable rules for AI in the United States. However, social enterprise, of which non-profits are a part, is not the gap filler and should not be perceived that way.

Non-profits like the OpenAI Nonprofit have social entrepreneurship features that can be found in other legal forms for social enterprise. Low-profit limited liability companies (L3Cs), benefit limited liability companies, statutory public benefit limited partnerships, social purpose corporations, benefit corporations, and their variants, such as Delaware public benefit corporations, are legal forms for social enterprise. They were created in the early 2000s in the United States to specifically produce a public benefit, or public benefits, and operate in a responsible and sustainable manner.

Doctrinally, these forms bridge the apparent conflict between the shareholder-centric model, which prioritizes profits and dividend distribution, and the stakeholder model, which considers employees’ well-being, the environment, society, and humanity. The core question is whether boards of directors should focus primarily on profit or also on broader stakeholder interests. This issue is particularly complex because institutions, such as law and markets, interact with organizations in multifaceted ways. OpenAI’s structural design embodies this complexity, reflecting the nuanced balance between different organizational priorities.

Legal forms for social enterprise enable boards of directors to focus on public benefits without being held liable for violating fiduciary duties of care, loyalty, and good faith, provided they act in accordance with the specific statutory requirements of the chosen legal form. For example, Delaware public benefit corporations are required by law to create a public benefit, which is defined as “a positive effect (or reduction of negative effects) on 1 or more categories of persons, entities, communities or interests (other than stockholders in their capacities as stockholders) including, but not limited to, effects of an artistic, charitable, cultural, economic, educational, environmental, literary, medical, religious, scientific or technological nature.”

Non-profits are exempt from paying federal income tax under the Internal Revenue Code §501(c)(3). They include public charities or charitable non-profits and other organizations that meet specified requirements, such as social welfare organizations, agricultural or horticultural organizations, civic leagues, social clubs, labor organizations, and business leagues. Non-profits can generate profits but cannot distribute these profits to investors as dividends. This constraint led to the creation of Open AI Global, LLC, a capped profit arm of Open AI Nonprofit. Open AI Global, LLC allows for fundraising through capital investment and provides a mechanism to distribute dividends to investors, albeit with a cap on the returns. This structure enables OpenAI to attract necessary investment while maintaining its commitment to its mission-driven objectives and ensuring that profits are not prioritized over public benefit.

The social entrepreneurship features of non-profit organizations can present salient challenges, particularly when non-profits operate in complex environments and are linked to, or held by, for-profit entities, such as traditional limited liability companies (LLCs), corporations, benefit corporations, and their variants. The recent developments in AI bring forth difficult questions about humanity, philosophy, ethics, and power—questions that cannot be adequately addressed by using non-profits and social enterprises more generally as a byproduct. By byproduct, I mean artifacts designed out of existing legal forms for traditional business organizations, of which the bottom line is profit. Considering the specific purpose of social enterprises, they are not appropriate gap fillers.

The OpenAI case illustrates the limitations of traditional corporate governance in a new landscape increasingly dominated by powerful tech leaders and the evolving behaviors of market participants toward mainstream technology. It also paves the way for new research areas that aim to explain how the specific ownership structures of business organizations, particularly those owned by non-profits or other forms of social enterprises, influence those businesses’ goals and purposes. Furthermore, it brings attention to the regulatory challenges that arise from these unique organizational frameworks.

The tension between the need for regulation, which may only be possible through corporate self-regulation, and a corporation’s business purpose is an issue that OpenAI’s ownership structure laid bare. This is a significant concern, considering the potential social costs of AI and its impact on the development and protection of human capabilities, such as community participation and individual autonomy.

Non-profits and other social enterprises face a paradox. Their managers must balance investors’ and other stakeholders’ interests. However, the lack of a cohesive governance and regulatory system undermines the purposes for which these social enterprises were created, especially when managers are profit-driven. Currently, the mechanisms to address the governance shortcomings in AI research and deployment companies are inadequate. Two notable legislative approaches–the European Union AI Act and President Joseph Biden’s Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence—have emerged. However, these approaches have yet to solve the challenges of AI governance in the boardroom and the instrumentalization of social enterprise for this purpose.

More robust governance frameworks, grounded in a solid understanding of how markets, law, and societies institutionally complement each other, are necessary to balance the unique needs of social enterprises and their mission-driven purposes with the responsible development and deployment of AI.

Lécia Vicente is currently a Visiting Professor of Law at the University of Camerino, Italy, and is the Founder and Managing Director of the Global Law Observatory for Business (GLOB). She has been a fellow at several prestigious higher education institutions across the United States and Europe and has held multiple advisory roles within the United Nations system. Notably, she was an Advisor and Chief of Delegation for the Permanent Mission of the African Union to the United Nations during the 2016 UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. Additionally, she held an endowed professorship at Louisiana State University. She routinely delivers lectures, presents her work, and participates in various academic events in the United States, Europe, Canada, and Brazil.

This piece is based on her work published in the American Journal of Comparative Law titled “The Social Enterprise: A New Form of Enterprise?,” an Oxford University Press publication. As the United States Special Rapporteur, she also contributed the chapter “Social Enterprise in the United States” to the book “Social Enterprise Law: A Multijurisdictional Comparative Review,” published by Intersentia.