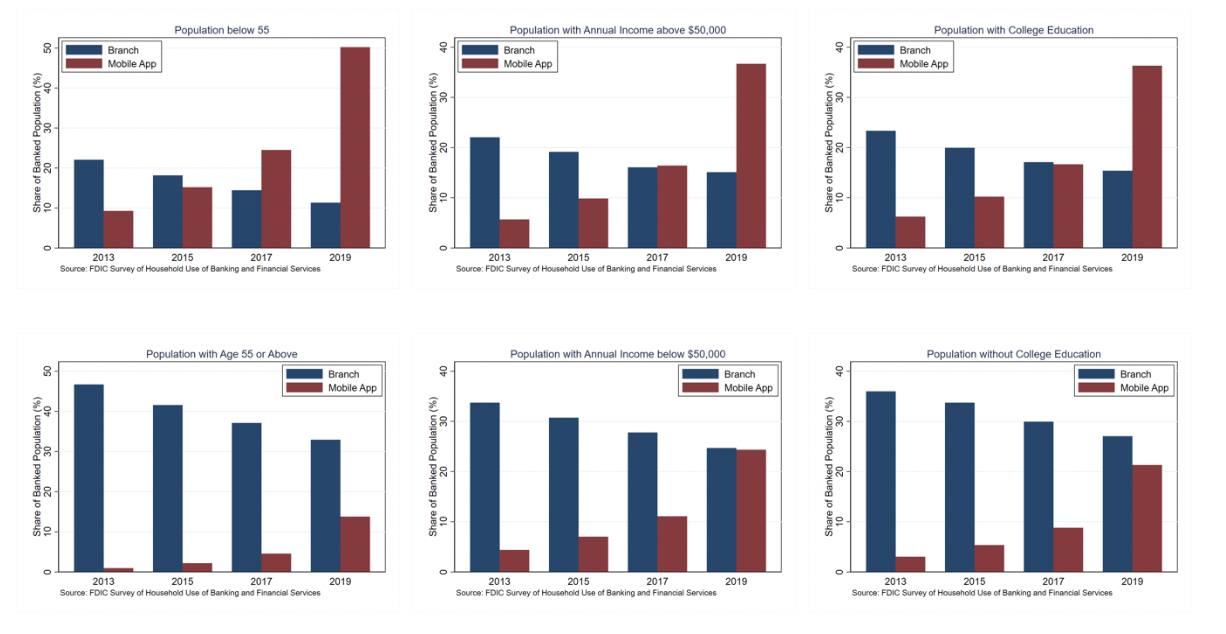

The impact of technological innovation on financial inclusion and the banking industry is central to policy discussions. The widely accepted view is that financial technology (“FinTech”) can democratize access to financial services, increase competition amongst financial intermediaries, and improve consumer welfare. However, not everyone has equal access to digital services, either due to a lack of capability or affordability. Policymakers call such a social phenomenon the “digital divide.”” Figure 1 shows a previously overlooked sharp divergence in how consumers access banking services over the past decade: younger, more educated, and higher-income consumers (“digital consumers”) adapt to digital platforms quickly, while older, less-educated, and lower-income consumers (“non-digital consumers”) still heavily rely on branches.

Figure 1: Share of the population relying on branches or mobile apps as the primary way to access banking services. Source: Authors’ calculation based on the FDIC Survey of Household Use of Banking and Financial Services.

In our recent working paper, we find that although digital consumers benefit from intensified bank competition, non-digital consumers bear higher banking service costs, suffer inconvenience, and are more likely to close their bank accounts following digital disruptions. The distributional effects of digital disruption work through banks’ endogenous responses to stay competitive in the disruptive environment.

Conceptually, our framework is as follows. Before digital disruption, consumers relied on branches to access banking services. Since operating branches was costly, a limited number of banks served each area. After digital disruption, banks can serve consumers remotely without having local branches. This invites more banks to a local market, making them compete more aggressively and imposing downward pressure on the prices of banking services. However, as digital consumers shift to digital services, branches become less appealing on average from the demand perspective. In response, incumbent banks shut down costly branches. In the meantime, non-digital customers are not tech-savvy and are captive to branching services. When fewer banks offer branches in the market, the remaining branching banks gain market power over captive non-digital customers and can charge higher prices. Consequently, digital customers benefit at the cost of non-digital customers who end up paying higher prices, suffer inconveniences, and face a higher risk of financial exclusion.

Our empirical exercise exploits the staggered introduction of the third-generation wireless mobile telecommunications (3G) networks. 3G technology is the critical infrastructure that allows users to browse the internet anywhere and access banking services without going to physical branches. As the 3G network gradually expands throughout the country, the setting provides substantial variation in the time series and the cross-section to implement statistical analyses.

We first establish a significantly positive relationship between the expansion of 3G networks and branch closures. The total number of branches decreases at the aggregate level when 3G networks fully cover the county. Moreover, banks account for consumer heterogeneity when they adjust their branching decisions: the impact of digital disruption on branch closures is stronger in counties with more young consumers who are more adaptive to digital services.

Digital services empowered by 3G networks allow banks to expand geographically without a branch. Over the past decade, we have witnessed the expansion of the geographic scope of competition from local to national. Take the mortgage market as an example. From 2009 to 2017, the number of counties covered by each lender has increased. The geographic expansion of banks increases local competition. We confirm that the expansion of 3G networks and the resulting changes in banks’ competing strategies partially contribute to these trends. Expanding 3G networks leads more banks to serve a region, intensifying local competition.

However, as banks close branches after digital disruption, non-digital consumers, who are less adaptive to digital services, are left with limited choices. Instead of competing for digital consumers, banks with a comparative advantage in operating branches strategically shift their focus toward these non-digital consumers and charge higher prices. The data shows such pricing behavior in both deposit and lending markets. In the deposit market, the deposit spreads charged by banks with branches increase with 3G coverage. Banks with more branches charge higher loan origination fees in the lending market as the 3G networks expand relative to banks with fewer branches.

The above findings collectively suggest that a new banking market structure emerges after the digital disruption: banks without a competitive advantage in operating branches compete on prices and serve consumers that prefer digital services, whereas banks with a competitive advantage in operating branches invest in branches, charge higher prices, and serve consumers that rely on branch services. As the banking sector shifts to this new market structure, digital consumers benefit at the cost of non-digital consumers.

Consistently, we show that non-digital consumers pay higher prices to access banking services –– higher mortgage origination fees and deposit spreads –– after 3G expands in a region. Moreover, survey data shows that non-digital consumers, including those who are more senior, lower income, and less educated, are more likely to be excluded from banking services after 3G arrives in town. Importantly, the 3G expansion partially increases the unbanked rate of non-digital consumers by causing those previously banked individuals to lose banking access. According to reported reasons for leaving banks of these previously banked individuals, the high fee is critical to their opt-out decision after the 3G networks arrive.

Our research finds that the disadvantaged non-digital population can face an even higher hurdle to accessing financial services when financial intermediaries change their strategies in response to digital disruption. Through a structural model, we assess the extent to which minimum branching requirements can help alleviate the resulting distributional effects amid digital disruption. While regulations can disproportionately help the non-digital population as they impose restrictions on branch closures, a larger required minimum number of branches may deter the entry of banks, reducing welfare, especially for non-digital consumers. Therefore, our research emphasizes the importance of considering the supply side adjustment when regulating banks’ branching decisions while developing digital services.

Erica Jiang is an Assistant Professor at USC Marshall.

Gloria Yu is an Assistant Professor at Singapore Management University.

Jinyuan Zhang is an Assistant Professor at UCLA Anderson.

This post is adapted from their paper, “Bank Competition amid Digital Disruption: Implications for Financial Inclusion,” available on SSRN.

[1] Digital disruption means the emergence of adisruptive technology that could change the way businesses have traditionally operated. In our context, we focus on the disruptive change in how consumers access the banking services after the emergence of digital banking.