The following post is the author’s combined oral and written testimony presented to the U.S. House Committee on Financial Service’s Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship and Capital Markets for a hearing entitled, “Climate Change and Social Responsibility: Helping Corporate Boards and Investors Make Decisions for a Sustainable World” on Thursday, February 25, 2021. A video of the hearing along with the written testimony of all witnesses can be accessed here.

Introduction and Summary

Thank you, Chairman Sherman and Ranking Member Huizenga. I am Andy Green, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. These remarks reflect my own views.

The problems facing our world—from climate change to system racism to economic inequality—are problems that investors directlyface too. Disclosure and accountability are not about subjective values and preferences. They are about making the economy work. Information and accountability are the lifeblood of competition and the broadly distributed economic opportunity that makes capitalism in America work—if we hold true to it.

Consistent, comparable, and reliable information, together with corporate governance accountability tools and strong banking regulation, enable investors and the public to help align outcomes for the long-term shared interests of all—investors, companies, workers, and the public. When those outcomes are not so aligned, financial crises, corporate scandals, taxpayer bailouts, pollution, racism, and economic inequality far more easily occur.

Climate change is a systemic risk to the U.S. financial system and many ESG matters pose growing threats to investor protection, retirement security, and economic growth. Climate change will destroy assets and hamstring recovery and growth. The need to transition to net zero will leave behind those who are laggards. And as scholar Graham Steele has outlined, climate’s impacts on the financial system amplify existing vulnerabilities, in particular leverage, interconnectedness, and concentration. Unless investors and regulators do more to prevent a climate “Lehman Brothers moment,” working family investors and taxpayers will be left holding the bag.[i]

We need equitable solutions for communities of color, agricultural communities (many of which are communities of color too), and all Americans who are similarly geographically impacted. Capital can move across borders in minutes, yet working families are far more bound to the communities in which we all live. We need to lean against the downward pressure that mobile capital can place on worker wages, environmental standards and more, be in within the country or internationally. Laissez-faire rules get you concentrations of wealth and economic power, and ultimately deep distrust in the political system that enables that.[ii]

Equity is only one of the reasons why I feel so strongly about a focus on financial sector transparency and accountability around the emissions it finances, the labor practices and tax risks it enables, and other ESG issues. Ultimately, it’s far more equitable to hold accountable the large financial firms that are financing, underwriting, and trading in climate-risk or labor-risk than it is to smack the community banks and credit unions serving working families and farmers. Bringing down emissions across the financial system will reduce the climate impacts on those communities and on all of us. Getting to net zero by 2050 is the best way to reduce climate financial risk.

Similarly, holding the financial sector accountable on worker empowerment, systemic racism, tax fairness, and human rights and democracy will send powerful signals, through the marketplace, that we are all in this together.

For too long, the United States has been a laggard in sustainable finance. Correcting that presents an opportunity: for better markets, and for American leadership in the world. Today the Subcommittee considers a number of important bills all of which advance sustainable finance, and which I supplement with a range of recommendations. All of these areas interact with one another in multiple ways, and progress across them together reinforces the effectiveness of all of them.

Below is a sampling of the recommendations I set forth below, and a recommendations appendix can be found at the end.

Starting with investor protection and retirement security:

- ESG disclosures: [iii]

- Climate risk, including financed emissions across the financial sector, transition target and plans, and sectoral adjustment strategies;

- Inequality and worker practices;

- Race and gender diversity, equity and inclusion;

- Tax transparency, in particular on a country-by-country basis;

- Human rights and supply chain risks; and

- Political spending and other forms of democracy protection.

- Disclosure of a sustainable investment plan for investment advisors.[iv]

- Strengthening corporate governance accountability, including access to shareholder proposals. [v]

- Closing loopholes around large companies in private securities markets. [vi]

- Credit rating and bond market standards.[vii]

- Vigorous auditing of climate-related risks.[viii]

Prudential regulatory and consumer finance policy interventions include:

- Stress tests and supervision, including on climate and on worker issues.[ix]

- Bank capital on carbon-intensive assets, including trading assets.[x]

- Looking at the Volcker Rule around climate-related risk-taking.

- ESG banking transparency for consumers and small businesses and facilitating their ability to switch accounts.

- Measuring and disclosing the financed emissions of government credit programs.[xi]

Climate community finance regulatory policy actions include:

- Incorporating climate into the Community Reinvestment Act and enhancing CRA tools more broadly.[xii]

- Greening the various Treasury Department small business and mission-driven programs.[xiii]

- Securing America’s agricultural finance sector against climate systemic risk.[xiv]

Our history of predicting past financial or investor protection crises is poor, but we have the opportunity to get it right this time. I hope we seize the opportunity. Ultimately, it’s about enabling capitalism to work.

Economic Outcomes for Companies and the Public Interest Have Diverged

On the surface, America’s investors and companies seem to be doing extraordinarily well. America’s corporate sector weathered the COVID-19 pandemic recession quickly, thanks to extraordinary levels of support from the Federal Reserve and the government. The sector overall returned to profitability: from July to September 2020 corporate real (inflation-adjusted, before tax) profits jumped by 58 percent and clocked the largest amount of real profits since the end of 2014. The profit rate (profits to assets) during that period was also higher than the fourth quarter of 2019, before the recession hit.[xv]

Yet these profits reflect a shockingly large divergence from the outcomes for the country as a whole. An insurrection built on a toxic combination of racism and the collapse of confidence in our national institutions; a pandemic where stock markets have soared but workers and small businesses have suffered; continuing waves of police brutality and racial injustice that sparked extraordinary waves of protest; intense weather disasters all cross the country, including fires of such intense strength they turned the West Coast pitch black in the middle of the day; and on and on.

A closer look reveals another gap between the overall economy and working families, reflected in the concentration of wealth and power at the top, which has been growing dramatically. For starters, the civilian labor force participation rate has been trending downward since 2001 but fell off a cliff in the pandemic.[xvi] (See Figure 1.) The labor share of national income has similarly fallen dramatically since 2001.[xvii] (See Figure 2.) The collapse of good jobs that underscores this decline has been overwhelming borne by working class Americans—those without four-year college degrees.[xviii] (See Figure 3.) Yet, even while working class Americans face challenges, those at the very top are doing exceedingly well. (See Figure 4.) Moreover, increases in taxes on working families have essentially made up for the decline in corporate taxes.[xix] (See Figure 5.)

An increasingly small number of companies make up a larger and larger percentage of aggregate corporate profit. Six companies make up half of the NASDAQ 100 and 17 percent of the S&P 500 value by market cap. Meanwhile, heightened levels of corporate profits are not competed away – a surefire sign that America has a monopoly problem as well.[xx] (See Figure 6.)

The racial wealth and income gaps that Black Americans face, together with the range of extraordinarily damaging forms of unfair treatment across society, and the continuing gender pay gap and representation gap in America’s business sector, also highlight the continuing painful distortions wrought on working families by structural inequities.[xxi] (See Figure 7.) The inability of America’s companies to fully face the unfathomable amounts of economic value at risk from the already occurring climate crisis presents a failure of leadership of catastrophic proportion. [xxii] (See Figure 8.)

In the face of this persistent gap in outcomes and risks between the capital markets and the lived experience of working families, it should not be surprising then that working families across the partisan divide believe that the economic system is rigged in favor of the wealthy and powerful.[xxiii] That this belief in—and, indeed experience of—a rigged economic system could be contorted into belief in a rigged political system perhaps should not surprise us, even while it shocks us.[xxiv] That Black, indigenous, and other communities of color have long experienced first-hand the injustices of actually rigged, or insufficiently unrigged, systems—from the workplace to politics to the environment and beyond—only underscores the depth of the change needed.

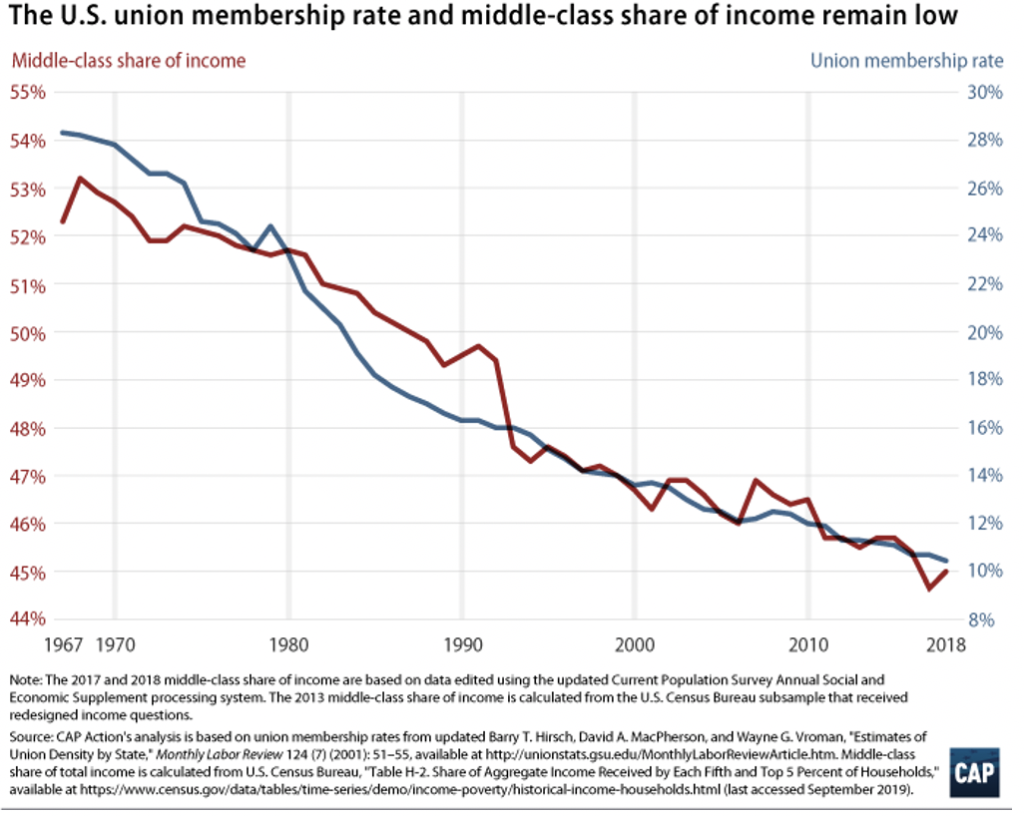

The origin of the growing gaps in outcomes between the corporate sector and the public interest are multifaceted. The assault on worker bargaining power in the United States is a large one. In earlier decades, multiracial unions played an essential “corporate governance” role as a key check on companies, in particular negotiating to ensure working families of all backgrounds shared in the profits of companies so that they could enjoy a middle-class life.[xxv] The benefits of strong unionization rates lifted all workers, not just those who were union members, as the benefits unions negotiated became to some extent standard across the labor market.[xxvi] (See Figure 9.)

Financial market and corporate governance changes have also played important roles. Securities regulatory changes since the 1980s have significantly eased the ability of companies to engage in share buybacks, opened the door for companies to grow large in opaque private securities markets, reduced the accountability of gatekeepers such as accounting firms, and failed to keep up with the demands for transparency across a wide range of environmental, social and governance matters. The resulting rise of short-termism across the corporate sector has been widely criticized. [xxvii] Swing-for-the-fence risk-taking, regulatory failures, fraud, and systemic impunity before and after the 2008 financial crisis destroyed jobs and opportunity, and undermined the wealth of millions of Americans, in particular Black Americans.[xxviii]

Other key factors include:[xxix]

- Expanded low-standard international trade, in particular trade with jurisdictions that do not maintain those same labor rights, have failed to enforce sufficient environmental protections, and provide large handouts to companies;

- Tax policies that have repeatedly cut corporate, high-income, and wealth taxes;

- The gutting of antitrust law as a check on corporate consolidation and market power;

- Failure to confront the legacies of systematic inequality along race, gender, and other lines; and

- Failure to make the necessary reforms to secure democratic political accountability so critical to policies such as climate.

Financial Regulation and Corporate Governance Are Important Tools for Aligning Outcomes

No one expects financial regulation and corporate governance to solve all of the country’s problems alone, but they have critical contributions to make.

Sound regulation of the financial system is the difference between decades of stable banking that served customers and economic growth, and a casino-like banking system that made proprietary trading and hedge fund and private equity fund bets, drove toxic lending practices, and ultimately drove the world economy to ruin and cost millions of Americans their jobs and homes.[xxx] How and whether the banking system will incorporate the new range of risks now being identified will also determine whether we have a financial system that serves long-term economic growth or whether we will see further shocks and collapses.

Securities regulation and corporate governance too have important roles to play to aligning executives, corporations, investors, workers, and society to better tackle our greatest challenges. Effective corporate governance can serve the long-term interests of stakeholders by ensuring that shareholders can hold directors and management accountable.[xxxi] The basics of transparency and accountability are vital to promoting the formation of capital to drive useful innovation and jobs, while also protecting investors.[xxxii] At a basic level, without complete and accurate information, investors will misallocate capital, which will be a drag on the economy and hurt overall investment returns.

The federal securities laws were initially adopted not just to protect investors from fraud, but to provide “full and fair disclosure” of information so that investors could put their capital to its most productive uses (as opposed to wasteful enterprises or scams).[xxxiii]

As the SEC explained on its website until very recently,

Only through the steady flow of timely, comprehensive, and accurate information can people make sound investment decisions. The result of this information flow is a far more active, efficient, and transparent capital market that facilitates the capital formation to our nation’s economy.[xxxiv]

While this has always been true, it is especially true with ESG-related information. Time and again investors, workers and the public have been able to utilize the power of shareholder democracy and the simple power of capital allocation to secure important reforms that prevent the upward transfer of investor, worker and often taxpayer wealth to corporate management and ensure that companies begin to address the range of challenges that they share with workers, communities, and the public writ large.

But these actions have often been met with politically motivated push-back. It is no accident, for example, that the SEC last year moved to seriously constrain shareholder voice despite strong investor opposition.[xxxv] Independent proxy advisers have also come under repeated attack. And the very foundations of disclosure were undermined by last year’s shift to management-determined principles-based disclosure. All of this occurs against the backdrop of the need for far more and better information from companies about their ESG risks so that investors and other creditors, including workers’ pensions, suppliers, and banks, may better appreciate and adapt to them.

Climate Change Is a Systemic Risk to the U.S. Financial System and Many ESG Matters Pose Growing Threats to Investor Protection, Retirement Security, and Economic Growth

Climate change’s threats to the financial system are generally divided into physical climate risks and transition risks.[xxxvi] Physical risks tend to drive systemic financial risk over the longer run and at more catastrophic levels, while transition risks are more immediate as the economy transitions to avoid the more severe set of physical risks down the road. These risks interrelate, as the more effective the financial system is at adjusting to transition risks, the more likely we also are at avoiding physical risks further down the road. That is, where financial firms and the real economy are aligned with the net zero emissions goals of 2050, which scientists indicate is essential, the better off the overarching system is.

Physical risks are the extreme weather and other environmental changes that damage property, productivity, and household wealth and impair financial system assets and income. These risks will emerge most likely slowly over time but could move quickly and in unexpected ways. Mortgage loans, commercial real estate assets, agricultural lending, derivatives portfolios, and other assets are all at risk of declining in value, in some cases significantly.

Some of the hardest hit communities will be those already economically vulnerable, including communities of color. As with the 2008 financial crisis, economic activity will decline, household income and wealth will be hit, and access to capital will diminish as a result—except it will be worse in these circumstances as many places will be ongoing disaster zones that cannot reasonably and efficiently be rebuilt. The significant overlap between climate impacts on communities of color and historical (and on-going) discrimination is troubling.[xxxvii]

Nationally, households and small businesses will face growing financial insecurity, which will further undermine financial system stability and have broader ripple effects on the economy and society, including political stability. This can be expected to drive an increase in default rates and negatively impact business lending at banks. Millions of retirees and would-be retirees can be expected to experience sharp, and possibly catastrophic, losses in the value of their retirement investments. And insurers, too, are expected to be on the hook for enormous losses, with many areas increasingly unable to obtain insurance at all—which itself would impair lending and other economic activity.

Transition risks also pose important challenges to confront. The transition away from fossil fuels is already occurring as policy, technology, and consumer and business choices evolve, in some cases rapidly. Indeed, the fossil fuel industry has been rocked by the pandemic, but its financial challenges have been growing for years. The next generation of consumers and business owners will only drive this evolution more quickly. For the financial sector to continue to assume that the future will be the same as the past is to turn a blind eye to these trends, at the risk of deceiving investors and exposing the taxpayers. Valuations for equities, bonds, and other instruments will change, possibly quickly. Former Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney has coined the term a “climate Minsky moment” to refer to the danger of rapidly declining asset prices arising from the collapse of the carbon bubble.

As scholar Graham Steele has outlined, climate’s impacts on the financial system will flow through and amplify the already wide-ranging set of risks that exist, in particular leverage, interconnectedness, and concentration.[xxxviii] Unless regulators do more to prevent what Steele terms a climate “Lehman Brothers moment,” working family investors and taxpayers are likely to be left holding the bag.

How and when all of this could turn from a slow-burning set of losses to a full-blown financial crisis is hard to predict, but the impacts of today’s choices will be long-lasting. The timeline for climate change’s impacts is in the decades, with damage increasing exponentially as emissions from today and in the years to come compound with those already in the atmosphere. Even while the catastrophic force of climate on the nation’s financial system and retirees may be decades away, the damage is already being felt today in agricultural, coastal, flood zone and drought and fire-prone communities, and more. The costs of disasters have grown dramatically in recent years. The fiscal impacts and impacts on national productivity are significant and not to be ignored, and support a case for the use of macroprudential regulatory tools to be deployed in support of effective long-run monetary policy.

Moreover, our history of predicting past financial crises is poor, especially in recent decades as thinly capitalized financial institutions have been deregulated to operate across increasingly lightning-fast trading markets. Prior to 2008, most of the top economic leaders repeatedly indicated that losses in subprime mortgages would be contained. And yet they were not, owing to unexpectedly large and unstable trading positions at hedge funds affiliated with large dealer-banks, at trading desks in large dealer-banks, and in derivatives bets by large insurance firms, among others. Similarly, the Asian Financial Crisis’s impacts on Russian debt were not specifically predictable, nor was the resulting collapse of Long-Term Capital Management, the hedge fund whose rescue was necessary to prevent the collapse of the other large Wall Street dealer banks whose proprietary trading desks had engaged in the same trading leveraged strategy. And on and on. We can go back much earlier for an example that could be insightful for climate: the panic of 1907 in New York was a direct result of the insurance claims from the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which led to an unexpected run on the banks of the day. We don’t have to conjure scenarios too far-fetched to recognize that climate change could, and may well be more likely than not, to result in serious stress on the financial system, or worse.

Equitably Mitigating Climate Financial Risks Requires Focusing on Their Root Causes

Financial Regulation Can Help the Economy Hit its Net Zero Imperative

Investments in and standards around a clean energy future are essential to tackling climate change head on, which is fundamental to reducing systemic financial risk and moderate the risks to investors, retirement security, and economic growth. Investments and standards can mitigate the physical risks while also providing avenues for transition risks to be absorbed more easily, as new opportunities for economic growth emerge from them. Yet even while fiscal investments and energy regulatory policies are fundamental, the financial system and financial regulation have critical supporting roles to play, especially to address the climate-related challenges that exist within their mandates.

Regulators need to work together to address the range of overlapping challenges to financial stability, monetary policy, institution safety and soundness, investor protection, retirement security, housing security, and consumer financial protection, which is why leadership by the Financial Stability Oversight Council will be so important. While much work remains to be done to deepen our understanding and map out interconnections and unexplored vulnerabilities, we must also recognize that tremendous amounts of light have already been cast upon the challenges.[xxxix]

Enhancing the overall resilience of the financial system is critical

The starting point for sound climate risk-management in the financial system is to restore sensible regulatory approaches designed to enhance financial system resiliency and investor protection to unexpected risks of any variety.[xl] Restoring and enhancing the financial system’s overall resiliency to shocks may be the best and most equitable way to address many of the expected and unexpected physical risks that arise from climate change.

Rolling back the recent deregulatory actions around bank capital and stress testing and the Volcker Rule, finishing the job in a strong way to limit mutual fund exposures to derivatives and other forms of leverage and liquidity risks, taking a new look at approaches to broker-dealer capital (such as were implicated in the Gamestop trading freeze that hit retail investors), enhancing and protecting Treasury, bond, and derivatives market transparency and resiliency can all play a role in ensuring that the financial system, investors, and consumers are more resilient to the unexpected but likely shocks that will emerge as the planet undergoes a certain amount of already unavoidable climate change.

Equity dictates a focus on tackling climate financial risk at the root: financed emissions

Climate risk management demands specific analysis and specific financial regulatory actions. Equity, and in particular racial equity, must remain at the forefront of policymakers’ minds, in financial regulatory and climate policies generally and at the intersection of the two specifically. Communities likely to be heavily impacted by climate change—including, for example, communities of color located in low-lying flood zones, agricultural communities exposed to drought or weather shocks, and working family communities exposed to regional shocks—are often unable on their own to avoid or affordably mitigate climate risks. While the geographic implications of climate change for financial institutions operating in those areas must be understood and monitored—and, indeed, the risks they face should motivate action generally—nevertheless caution should be exercised regarding exactly how climate risk is managed from a financial regulatory policy perspective. The world has a narrow window to mitigate climate risk generally, including to the financial system, by limiting it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. This requires net zero emissions by 2050, with significant progress toward that goal accomplished over the next ten years.[xli]

The largest marginal emissions are in a handful of carbon-intensive sectors, with the largest financiers of those emissions similarly concentrated at the largest banks and in certain bond markets and leveraged lending markets.[xlii] In ordinary systemic risk policies designed to mitigate “too big to fail” (TBTF), policymakers ask the largest banks to internalize the costs of the TBTF-pollution through higher capital charges and stricter regulation overall. So too in climate, we should be first asking the heavy financiers of the actual pollution—emissions—to address that pollution squarely. This will principally be some of the largest banks and asset managers. However, it may also include emissions-intensive smaller banks, lest we forget the necessity of bailing out Continental Bank of Illinois in the 1980s when loans to a smaller bank funding speculative oil drilling failed.

A focus on financed emissions and carbon-intensity in financial activity will enable investors and lenders to allocate capital in a long-term more efficient manner, so that carbon does not enjoy unfair subsidies compared to the economic and social costs associated with cleaner energy. As activities can migrate between bank and non-bank markets, both regulators and investors will need to deploy the range of available tools to address the particular risks of carbon-intensive financing activities and align the financial system with the systemic necessity of net zero financed emissions by 2050.

Securities regulators can utilize tools such as disclosure of financed emissions, transition plans and targets, and sectoral adjustment strategies. They can also improve credit ratings, support vigorous audits, deploy enforcement cases, and more. Securities regulators and retirement security regulators can mandate the development and disclosure of sustainable investment policies by the advisers to fiduciary funds. Federal and state financial institution regulators can examine for plans and targets, enforce constraints on activities, and deploy capital charges. Tools such as the Volcker Rule that constrain high-risk assets and high-risk trading strategies may be appropriate to deploy as well. Risk monitoring entities can look for emerging gaps and designate firms or activities as systemically significant. Data sharing will be essential. For example, Form PF will need to be updated to cover financed emissions and other climate-related risks, with the information more readily shared with FSOC and member agencies.

Other regulators and adjacent agencies can play supporting roles as well. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau can empower consumers to vote with their feet through enhanced information on climate and other ESG performance of their accounts and greater ability to switch accounts. Housing and agricultural finance regulators can reduce risks to the taxpayer by examining for the financed emissions of the originating bank and its affiliates. Programs that support mission-driven lending and small business support, such as the Community Reinvestment Act, CDFI Fund, the Small Business Lending Fund, and even the credit union system more broadly, can be retooled to enhance lending to communities that need support making the clean energy transition. And more.

No one expects the financial system to have complete control over the clean energy transition of their customers. But the cost of capital to those customers should reflect the systemic risks that carbon poses, both financial stability risks and macroprudential risks to economic growth. And, they are in a position, in general, to obtain information, such as the customer’s emissions, much like they already do around risks ranging from terrorist financing to basic financials. There are also reasonable ways for financial firms to estimate, which can also help them engage in risk management. Placing a greater obligation on the financial system can also incentivize it to play the much-needed catalytic role in financing the sectoral transformations needed to reduce emissions across currently carbon-intensive industries—as pioneered by the Rocky Mountain Institute’s work on the shipping industry.[xliii] It can also help cover gaps in disclosure and accountability arising from the growing role of private securities markets.

Importantly, clear, simple, and transparent measurements are essential for holding the financial system and financial regulators accountable for the net zero necessities of climate risk in the financial system. Complex measurement tools are valuable for a range of regulatory and risk-management purposes, but they need to be undergirded by the basics of disclosure: emissions and, for the financial system, financed emissions.

Financed emissions disclosure will not only be important for the private financial system, but also for government credit agencies. Financed emissions measurement, together with the goal of net zero by 2050, can help align both government and private credit with the needs of managing climate risk management. It can also ensure that the government does not end up holding large amounts of climate risk off-loaded from the private sector. Managing the financed emissions of the issuers (and their affiliates) of those that sell to government credit portfolios is also a more equitable means—especially on matters of racial justice—and a more effective means of managing climate risk at its root than focusing exclusively on the aftereffects of climate change which, were emissions more aggressively reduced, can still be avoided. Many of the tools described above can and also should be viewed, in part, as macroprudential tools in support of mitigating climate as a monetary policy risk.

Representative Casten and Senator Warren’s Climate Risk Disclosure Act and Representative Velasquez’s Paris Climate Disclosure Act both provide vital disclosures to help investors measure, manage, and mitigate climate risk.[xliv] A range of other legislation also provides a critical pathway forward, such as Representative Casten and Senator Schatz’s Climate Change Financial Risk Act and Senator Merkley’s Protecting America’s Economy from the Carbon Bubble Act.[xlv] These are only some of the legislation that has and could be introduced to spur much-needed action to protect taxpayers, investors, and the planet.

Financial Markets Need Information on A Broad Range of ESG Matters To Drive Sustainable, Efficient Outcomes for Investors and the Public

Climate change is not the only ESG matter that has implications for the financial system, including for investor protection, retirement security and economic growth. Other environmental indicators, such as industrial pollution, land degradation, and deforestation, must also be properly reported.[xlvi] Sometimes grouped together as social issues, or employee and social issues, economic inequality and worker issues, race and gender issues, tax transparency, human rights, and democracy protection are just a few of the examples where the financial system, and in particular the capital markets, need to better take account of ESG matters and sustainability to make capitalism work. To that end, Representative Vargas’s ESG Disclosure Simplification Act, which mandates certain ESG metrics reporting, creates a sustainable finance advisory committee at the SEC, and creates a high-standard reporting backstop if the SEC does not act, highlights the need to make progress on all of these important fronts.[xlvii]

Worker issues and inequality provide an example of why this is so. The collapse of workers’ faith in their ability to be part of a robust and inclusive middle class has given rise to political instability in the U.S. and poses risks to the rule of law and beyond. These developments are rooted, in significant part, to the decline of worker bargaining power and shifts in corporate governance, financial regulation, and antitrust enforcement. These changes have empowered extraordinary levels of corporate wealth transfers to the very wealthy via executive compensation, share buybacks, and mergers and acquisitions, while leaving wages for non-college educated workers largely stagnant for decades, forcing families to compensate by working more. Congress began to address those issues in the Dodd-Frank Act with disclosure of the CEO-worker pay ratio, but far more needs to be done.[xlviii] Collective bargaining should be the norm at regulated financial institutions and much more widely across the economy, and banks and investors should take into consideration in their investing and lending decisions the economic and social risks arising from poor labor-management practices. Representative Axne and Senator Warner’s Workforce Investment Disclosure Act, which provides critical disclosures regarding workforce investments and practices, and Representative Velasquez’s Greater Accountability in Pay Act, which provides important benchmarks regarding executive compensation, would both further greater transparency and accountability around worker and inequality issues.[xlix]

As Chairwoman Waters’ groundbreaking subcommittee focusing on diversity, equity and inclusion has shown, race and gender issues are areas that need far greater attention in the capital markets and financial system more broadly. Recently, Majority Action and the SEIU highlighted how systemic racism has manifested itself in board rooms with few or even no Black directors, and some without any persons of color. As of their 2020 annual meetings, more than one third (178) of S&P 500 companies had no Black directors, while one out of ten had no directors of color.[l] Multiple studies including those by the state of California highlight how women continue to face high levels of systemic discrimination and challenges securing board seats and other corporate leadership positions.[li] Deep systemic discrimination and on-going practices of harassment and abuse (some blatant and some more hidden) impact the ability of persons of color and women to advance in many companies. Some of these problems can be corrected by management tracking numbers and setting targets for improvement.[lii] Transparency and accountability to investors and the public are important tools for progress across a wide range of bias, including gender and racial pay gaps.[liii] Moreover, as the Majority Action-SEIU report highlights, how asset managers vote their proxies matters greatly as well: for the entire boards that have no Black directors and others without any persons of color, two of the nation’s leading asset managers cast votes of support more than 90 percent of the time.

Representative Meeks’ and Senator Menendez’s Improving Corporate Governance Through Diversity Act would facilitate much-needed diversity transparency on boards by focusing the attention of management on these issues.[liv] Additional transparency for ESG expertise and constituency representation on boards would be valuable, as would greater transparency and accountability regarding asset manager proxy voting.[lv] Greater attention to diversity in the workforce overall is also essential, which is reflected in the Axne-Warner legislation and other efforts by the Human Capital Management Coalition to boost worker disclosure.

Tax planning strategies minimize tax payments to governments but expose companies to tax enforcement liabilities.[lvi] They also highlight significant financial risk where tax strategies hide underperformance of actual operations—which has been a major factor in the collapse of name-brand companies.[lvii] Both pose significant risks to investors that must be understood and evaluated. Moreover, with corporate nominal and effective tax rates having fallen for decades, the broad risks to fiscal stability from widespread corporate tax minimization must not be ignored. Investors deserve the ability, on a country-by-country basis, to understand the strategies that companies use and evaluate for themselves whether those strategies are wise or irresponsible. Indeed, country-by-country tax transparency is gaining currency worldwide. Investors representing over $1 trillion in assets under management have petitioned and engaged with the Financial Accounting Standards Board to provide country-by-country tax transparency as an accounting matter.[lviii] The European Union, OECD, the Global Reporting Initiative, and a growing number of private companies are moving on this form of investor-friendly transparency.[lix] Representative Axne and Senator Van Hollen’s Disclosure of Tax Havens and Offshoring Act provides the country-by-country and other tax disclosures so important to protect investors and align business practice with sustainable fiscal policies.[lx]

Human rights abuses similarly pose risks to investor protection and economic growth that must be recognized and addressed. Supply chains that involve violence, corruption, and human rights abuses are subject to physical and reputational disruption in myriad ways.[lxi] Items made with forced labor are barred from the U.S. by law, so transparency across the supply chain around labor practices is essential.[lxii] Similarly, companies are increasingly making commitments to eliminating human rights abuses in their supply chains. For example, the Lesotho Brand Agreement, which addresses gender violence at certain textile suppliers, is enforceable against brands in U.S. courts, highlights why investors should appreciate those commitments.[lxiii] Congress recognized the importance of acting on these issues in the Dodd-Frank Act through its adoption of extractive industry payments disclosure and conflict minerals disclosure, although the SEC has had a tortured history managing these disclosures, including shunting some of them off to the side in Form SD Special Disclosure and facing Congressional Review Act challenges. Yet the pandemic has revealed that supply chain risks are more important than ever to address, and human rights violations are material supply chain risks. Chairman Sherman’s Oil and Mineral Corruption Prevention Act and legislation such as the Corporate Human Rights Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Mitigation Act, offer valuable pathways for action on reducing these prominent supply chain risks.[lxiv]

Political spending disclosure is a vital tool for addressing all ESG issues, as the distortions that political spending drives throughout the policy process are severe. In the aftermath of the events at the United States Capitol Building on January 6th, many companies quickly and publicly announced the halting of, or reforms to, their political spending activities. Clearly, they thought their spending was material to investors and the public. But investors, public interest advocates, and academics have felt this way for a long time. Over the years, there have been numerous requests to the SEC to require disclosures regarding corporate political spending, which have garnered more than 1 million comments in support. Despite this strong support—and indeed, the very assumptions baked into late Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion—the SEC has refused to (or been barred from being able to) act.[lxv]

Political spending may well be small from a balance sheet perspective, but its consequences are enormous. Why else would companies spend corporate funds, over which boards have fiduciary duties of loyalty and good stewardship? Indeed, political spending disclosure is a vital test to examine whether a company’s commitments on other ESG matters are real, or whether the company’s positions are undermined by opaque actions here in Washington.[lxvi] Even while political spending disclosure is now the norm, significant gaps exist and there remains a strong need for consistency, comparability, and reliability for investors.[lxvii] Companies are also now turning to a more comprehensive approach, such as the CPA-Wharton Zicklin Model Code of Conduct for Corporate Political Spending, and investors need information to monitor the outcomes.[lxviii] Representative Foster’s Shareholder Political Transparency Act is an essential step forward.[lxix]

Do Not Second-Guess Investors and the Public’s Need for Information

The federal securities laws are intended to provide investors and the public with information needed to protect investors, ensure fair and efficient market, and support capital formation.[lxx] The origins go back to the capital misallocation that contributed significantly to the 1929 financial crash. Over the years, the SEC has attempted to flesh this out by providing companies with clear, required disclosures, as well as guidance for when additional disclosures, such as “material risks” are warranted. Today, much of the debate is over what is “material” to investors. Unfortunately, this debate ignores the practical reality that it isn’t up to corporations, their executives, or even the SEC to make that determination.

Only investors can determine what is relevant to them. And only investors can determine what is “material” to their decision-making processes. Which is why it is striking that investors now overwhelmingly demand ESG information.[lxxi] Unfortunately, for years, many companies and their executives have sought to exclude ESG information from disclosures or avoid mandatory ESG related disclosures based on their own subjective interpretations of materiality.

Yet that line of thinking reflects a sleight of hand around materiality and an inappropriate application to rulemaking. The SEC has wide ranging authority to set the terms for disclosure in the capital markets, in the interests of investor protection and in the public interest more broadly. To the extent that the courts have limited enforcement cases to matters where an item of information was not material to a company, that relates to specific information and a specific company. The deployment of “materiality” to be a finding that is needed before it can be required by the SEC is a self-inflicted wound sought by issuer advocates who would seek to limit corporate transparency.

But even if materiality were to be applied as a standard for what ought to be disclosed in the context of rulemaking, the focus should be on whether the information is material to the reasonable investor. That a matter can be shown to be financially material to the company (generally, to the results of operations thereof)is undoubtedly a good indicator that the information is material to a reasonable investor. But that is not an exclusive determination. That is, investors may demand information for any reason; if enough of them demand the information, for any reason, that then becomes material to the “reasonable investor.” In this case, the explosion of ESG considerations by investors points to ESG information being highly material to reasonable investors.

Perhaps that is because investors who care about these issues today may in fact demonstrate a better assessment of long-term financial materiality than managers who are too closely focused on short-term profitability. That these financial materiality evaluations may also change rapidly suggest an approach that is even more deferential to the “dynamic” needs of investors for information.[lxxii] This task of evaluating the long-term financial risks and opportunities to companies is more pressing than ever given the growth of the universal owner—the investor that owns broad baskets of corporate America and so is unable to diversify away from many risks.[lxxiii] Such an investor may need a collection of information that paints a picture greater than the sum of its parts. It certainly is not the role of corporate management, or the SEC, to second-guess the competitive functioning of the capital markets.

As to what particular ESG information should be disclosed, that is where the SEC’s expert judgment, informed by the public comment process and any legislative actions by Congress, should be determinative. Such an approach is also far more cost effective. If the SEC—or even worse, companies—had to quantitatively prove the materiality of every item, it would be expensive and time-consuming, and investors would be left with little to no disclosure. The costs to capital markets efficiency and investor protection would be high.

Whether ESG incorporation is for narrow self-interested economic reasons or for broader social reasons, whether that be for the near term or for decades in the future, is of no consequence. The fact that investors are now overwhelmingly demanding greater ESG information and accountability is what matters. What is disclosed is ultimately for investors and the public to determine, via publicly accountable regulatory agencies like the SEC and other regulators, and not for corporate management and their lawyers and accountants. No one should confuse the application of the materiality standard in an enforcement case around very particularized facts and circumstances with the SEC’s definitive authority—where materiality finding requirements are not written in the federal securities laws—to mandate corporate disclosure across the market.

Enhance Public Markets

We must also be attentive to the growing trend of large companies avoiding the public markets. Public markets are important not only because of their transparency but also because of the structures of accountability built into corporate governance. In public markets, investors can engage management, bring shareholder resolutions, and vote for boards of directors. These tools have repeatedly proven their risk-management value.

Unfortunately, decades of deregulation of the offering of securities has meant that the majority of capital raised in our markets is now outside of these safeguards.[lxxiv] Corporate debt securities, for example, are mostly exempt from the disclosure requirements of the federal securities laws.[lxxv] The multi-year trend permitting the “corporate royalty” of dual class shareholdings as well as last year’s SEC deregulatory attack on shareholder proposals, have undermined the feedback mechanisms so important for investors and the public.[lxxvi] Investors have been at the mercy of decades of antitrust deregulation, which has further concentrated markets and reduced capital markets competitiveness and effectiveness.[lxxvii]

Because opportunities for investing in the public markets have dwindled over time, investors have little choice but to invest in the private markets, putting themselves at greater risk and exposing themselves to higher costs and higher level of problematic outcomes from the perspective of inequality and social stability.[lxxviii]

Instead, Congress and regulators should be promoting public company accountability, which should include ensuring that large companies, including those with significant revenues, numbers of shareholders (calculated by human beings, not brokerage firms), valuations, or employees, should be part of the public market regime. Further, Congress and regulators need to focus directly on promoting transparency and rights for investors in very large private offerings, particularly those that may carry long-term risks for investors, including offerings made through Rule 144A.

No one should confuse the large private market companies in need of meaningful oversight with the truly small companies and small offerings where the SEC has experimented with tiered approaches. With sufficient investor protections, including basic transparency, investment limits, well-regulated and accountable platforms, and limits on off-platform advertising, the risks to investors and the economy overall may, in theory, be contained. However, experiments by Congress and the SEC in these areas suggest caution remains in order. Many efforts (such as Regulation A+) have led to disappointing results for investors and fraud.[lxxix] The SEC’s recent steps to further expand those provisions, together with the accredited investor definitions, are steps in the wrong direction. Tailoring requirements and responsibilities for truly smaller companies that pose fewer risks has, for too long, been used as cover for sweeping deregulation.

Sustainable Finance Is An Opportunity to Regain American Leadership

The agenda outlined above first offers a powerful means for aligning our domestic markets with long-term public interest outcomes. But it also offers a sensible agenda for aligning U.S. markets with more sustainable international markets, to the benefit of U.S. leadership and private sector compliance in a global marketplace.

U.S. workers and businesses are competing in markets whose impacts can be rapidly felt across borders. While there is much that the U.S. can do within our borders to empower workers, enhance racial equity, address climate change, and rebuild from the pandemic with a stronger, more inclusive economy, without aligning international markets in those directions we are making our work that much harder. Between the early 1990s and the mid-2000s, the labor market in which the U.S. worker competed more than doubled, and it has continued to grow. If those markets do not have sufficiently robust worker rights, climate and environmental protections, tax collection, and democracy and human rights standards (including political transparency and anti-corruption protections), American efforts to improve our society will be fighting the power of internationally mobile capital seeking the short-term cheapest production base, now supercharged by increasingly monopolistic technological and (for all practical purposes) vertically integrated platforms.[lxxx]

Our international partners are recognizing that aligning markets with the long-term public interest is good economic governance. The risk-management essentials of climate are clear and discussed above. But the evidence from Europe also highlights how other aspects of a sustainable finance agenda can yield positive benefits for investors, companies, workers, and the public alike. For example, employee participation in corporate governance has been found to yield positive benefits for productivity, investment, and long-term financial performance, not to mention employee satisfaction.[lxxxi] Critically, inclusive economies are a vital first-line protection against authoritarian attempts to undermine democracy.

The European Union’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan is a robust plan for aligning their markets not only with climate risks but also with empowering workers, corporate tax responsibilities, and basic human rights standards. The United Kingdom is a leader in these areas as well, having made TCFD effectively mandatory and, through its 2018 Corporate Governance Code, which applies to UK-listed companies, mandates enhanced board engagement with employees via board representation of a work or a worker-focused independent director, or the formation of a worker council.[lxxxii] Japan, too, has indicated its intent to make TCFD mandatory and has recently convened a broader expert panel on sustainable finance. Australia and many other countries are following suit.[lxxxiii]

The initiatives are supported by the commitments of financial market participants themselves. Since its founding little more than a decade ago, the Principles for Responsible Investing now represents 3,000 investors and more than $100 trillion in assets, and its banking counterpart the Principles for Responsible Banking has grown robustly as well.[lxxxiv]

Action on ESG will also facilitate U.S. competitiveness. Ensuring that global financial regulatory rules, trade rules and other economic market standards enhance outcomes that undergird inclusive democracies represents a wise long-term investment in U.S. economic and political competitiveness. Indeed, such a vision was exactly what was on order when the Obama Administration set out the agenda for global financial reforms in 2009 the then-Pittsburgh G-20 meeting. This year, the G-7, the Summit of Democracies, and the Glasgow COP26 meeting, among others, offer a series of opportunities for the U.S. to seize the initiative around a vision for sustainable economics that incorporate climate, labor rights, and democratic ambition so essential to secure our world against climate change and the return of ethnonationalist authoritarianism.

Conclusion

Sustainable finance in the capital markets and banking system will not solve all of these problems on their own. But financial regulations can help align outcomes for investors, workers, management, and the public interest. Corporate transparency and accountability to investors in the capital markets is the starting point. Banking prudential and other forms of financial regulation can do far more risk management around sustainability.

Ultimately, it’s about enabling capitalism to work.

Andy Green is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress

Appendix (recommendations)

On climate, the available information today already points toward a robust agenda for action on climate across the following areas.

Investor protection and retirement security actions include:

- Disclosure of climate-related risks, including emissions and other climate risks; transition plan, targets, and sectoral adjustment strategies around net zero 2050; and special attention to disclosure and targeting of financed emissions across the financial sector.[i]

- The framework established by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and elucidated by private standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative, the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials, and others—many of them brought together by the Corporate Reporting Dialogue—ought to be the foundation for quick action by the SEC, with additional details and improvements brought about over time.

- These should be paired with broader ESG disclosures of other environmental matters (which are especially important for environmental justice reasons); worker treatment and rights issues; racial and gender equity issues in corporate leadership and workforce; country-by-country tax transparency; human rights along the supply chains; and political spending.

- Obligations should apply to public companies but also to large private companies that have taken advantage of the growth in loopholes to evade transparency and accountability.[ii]

- Requiring investment advisors that serve as asset fiduciaries to develop and disclose a sustainable investment plan that describes how they incorporate ESG factors, including climate.[iii]

- Strengthening corporate governance accountability, including the principle of one-share one-vote, access to proxy, voting transparency, and voting accountability for shareholder proposals and board seats; board diversity, including ESG expertise and constituency representation; and executive compensation alignment. [iv]

- Credit rating and bond market transparency and accountability around climate and ESG.[v]

- Vigorous auditing of climate-related risks.[vi]

Climate prudential regulatory and consumer finance policy interventions include:

- Stress tests and supervision on climate and other ESG-related systemic risks.[vii] Regulators should examine for the incorporation of climate-related concerns into risk management systems and should also engage with frontline workers and ensure enhanced worker protections for bank workers to protect whistleblowers and improve compliance overall.[viii]

- Bank capital should be raised on carbon-intensive assets, including trading assets, to ensure financial institutions fully internalize and disincentivize climate systemic risks their activities are creating.[ix]

- The Volcker Rule should be strengthened to enhance oversight of risk-taking, including climate-related risk-taking. High-risk assets and high-risk trading strategies are not permitted activities under the Merkley-Levin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act.[x]

- Insurance regulatory actions to parallel SEC actions on transparency and prudential regulatory actions around solvency, with FSOC designation to fill any gaps in insurance and in other markets.

- Empowering consumers and small businesses to better understand the climate and ESG-related risks in their accounts and other financial services, and to more easily switch accounts and close financial services without negative impacts on their credit. The prevention of predatory cycles of debt may also have a climate-related function to play, as working families without sufficient wealth will be more vulnerable to negative impacts of climate risk and less able to make any necessary adaptations if not fully supported by government policy.

- Elimination of Federal Reserve extraordinary support for the fossil fuel industry, and the measurement and disclosure by the Federal government, including the Federal Reserve, of the emissions its many credit and credit enhancement programs finance.[xi]

Climate community finance regulatory policy should support a just and necessary transition and protect community banks, credit unions, and agricultural lenders. Actions include:

- Incorporating climate into the Community Reinvestment Act and enhancing CRA tools more broadly.[xii] This may also take the form of a new stand-alone green finance mandate as proposed last year.[xiii]

- Greening the Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund program (or creating a stand-alone green fund parallel at the U.S. Department of Agriculture) and the Small Business Lending Fund (SBLF), and taking further steps to support mission-driven community banks, credit unions, and loan funds in order to make the necessary clean energy investments in communities that are often otherwise left behind.[xiv]

- Tackling climate risks at the housing finance enterprises and aligning clean energy lending with the housing opportunity and racial equity needs of low- and middle-income homeowners and renters.[xv]

- Securing America’s agricultural finance sector against climate systemic risk and enabling agricultural and rural lenders to support the clean energy transition.[xvi]

ESG disclosures and accountability more broadly should be dramatically expanded, including in the following areas:

- Inequality and worker practices;

- Race and gender diversity, equity and inclusion;

- Tax transparency, in particular on a country-by-country basis;

- Human rights and supply chain risks; and

- Political spending and other forms of democracy protection.

The corporate governance accountability tools with respect to climate, noted above, apply with equal force to ESG more broadly. Additionally, new efforts need to be made to expand disclosure and accountability to large private companies and close the loopholes that allow too many of them to evade the transparency and accountability, including auditing and internal controls, of the public markets—at significant costs and risks to investors.

It remains important as well to recall that the materiality standard is not a statutory requirement for SEC-mandated disclosure but is an enforcement defense for particular companies with respect to particular circumstances. Furthermore, materiality is tied, at a minimum, to what matters to investors for reasons they determine in their decision-making, and so needs to reflect investor priorities—which are best determined by the expertise of the SEC in consultation with investors, not by corporate management. Growing investor demand for ESG disclosure also highlights how investors who care about these issues may in fact demonstrate a better assessment of long-term financial materiality than managers who are too closely focused on short-term profitability. More broadly, the SEC has a public interest duty relating to the prevention of financial crises and misallocation of capital, which give it broad authority to secure transparency in the capital markets.

Appendix (Charts)

(Citations for each of the figures can be found in the footnotes in the main text.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Citations

[i] Graham Steele, “Confronting the ‘Climate Lehman Moment’: The Case for Macroprudential Climate Regulation,” 30 Cornell J.L.& Pub. Pol’y 109 (2020), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542840; see also Graham Steele, “The New Money Trust: How Large Money Managers Control Our Economy and What We Can Do About It,” (Washington: American Economic Liberties Project, 2020), available at https://www.economicliberties.us/our-work/new-money-trust/#.

[ii] Trevor Sutton and Andy Green, “Adieu to Laissez-Faire Trade,” Democracy Journal, Oct. 2020, available at https://democracyjournal.org/arguments/adieu-to-laissez-faire-trade/

[iii] Alexandra Thornton and Andy Green, “The SEC’s Time to Act,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2021), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2021/02/19/496015/secs-time-act/; Andy Green and Andrew Schwartz, “Corporate Long-Termism, Transparency, and the Public Interest,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2018/10/02/458891/corporate-long-termism-transparency-public-interest/.

[iv] Tyler Gellasch and Alexandra Thornton, “Modernizing the Social Contract for Investment Fiduciaries,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/11/18/492982/modernizing-social-contract-investment-fiduciaries/.

[v] Green and Schwartz, “Corporate Long-Termism, Transparency and the Public Interest,” supra.

[vi] Tyler Gellasch and Lee Reiners, “From Laggard to Leader: Updating the Securities Regulatory Framework to Better Meet the Needs of Investors and Society” (Raleigh, NC: Duke Law Global Financial Markets Center, 2021) available at https://web.law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/gfmc/From-Laggard-to-Leader.pdf.

[vii] Kevin DeGood, “Climate Change and Municipal Finance,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/05/06/484173/climate-change-municipal-finance/.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Gregg Gelzinis and Graham Steele, “Climate Change Threatens the Stability of the Financial System,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/11/21/477190/climate-change-threatens-stability-financial-system/.

[x] See, generally, Graham Steele, “A Regulatory Green Light: How Dodd-Frank Can Address Wall Street’s Role in the Climate Crisis” (New York: Great Democracy Initiative, 2020) available at https://greatdemocracyinitiative.org/document/dodd-frank-and-the-climate-crisis/;

[xi] Gregg Gelzinis, Michael Madowitz, and Divya Vijay, “The Fed’s Oil and Gas Bailout Is a Mistake,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/07/31/488320/feds-oil-gas-bailout-mistake/; see also Marc Jarsulic and Gregg Gelzinis, “Making the Fed Rescue Serve Everyone in the Aftermath of the Coronavirus Pandemic” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2020/05/14/484951/making-fed-rescue-serve-everyone-aftermath-coronavirus-pandemic/.

[xii] Zoe Willingham and Michela Zonta, “A CRA To Meet the Climate Challenge,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/12/17/493886/cra-meet-challenge-climate-change/.

[xiii] Olugbenga Ajilore and Zoe Willingham, “The Path to Rural Resilience in America,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/09/21/490411/path-rural-resilience-america/; Zoe Willingham, “Promoting Climate-Resilient Agricultural and Rural Credit,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2021/01/14/494574/promoting-climate-resilient-agricultural-rural-credit/; Melissa Malkin-Weber, David Beck Brian Schneiderman, and Philip E. Otienoburu, “The Climate Imperative and Community Finance: Regulatory and Policy Tools to Drive a Just Response,” (North Carolina: Self-Help Credit Union, 2021) available at https://www.self-help.org/docs/default-source/PDFs/climate-imperative–final-release-2102021.pdf?sfvrsn=2; Alexandra Thornton and Andy Green, “How Congress Can Help Small Businesses Weather the Coronavirus Pandemic,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2020/04/13/483067/congress-can-help-small-businesses-weather-coronavirus-pandemic/

[xiv] Zoe Willingham, “Promoting Climate-Resilient Agricultural and Rural Credit,” supra.

[xv] Christian Weller, “The Corporations Are Alright,” Forbes, Jan. 18, 2021, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/christianweller/2021/01/18/the-corporations-are-alright/?sh=21978e46323f.

[xvi] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Civilian labor force participation rate,” available at https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/civilian-labor-force-participation-rate.htm (accessed Feb. 2021).

[xvii] “Nonfarm business section: Labor share,” FRED Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PRS85006173 (accessed Feb. 2021).

[xviii] Center for American Progress, “The Blueprint for the 21st Century,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2018/05/14/450856/blueprint-21st-century/.

[xix] See Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Where Do Federal Tax Revenues Come From?” (Washington, 2020), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-where-do-federal-tax-revenues-come-from.

[xx] Ari Levy, Lorie Konish, “The five biggest tech companies now make up 17.5% of the S&P 500,” CNBC.com, Jan. 28, 2020, available at https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/28/sp-500-dominated-by-apple-microsoft-alphabet-amazon-facebook.html; see also Marc Jarsulic, Ethan Gurwitz, and Andrew Schwartz, “Towards a Robust Competition Policy,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/04/03/467613/toward-robust-competition-policy/.

[xxi] See Angela Hanks, Danyelle Solomon, and Christian E. Weller, “Systematic Inequality,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2018/02/21/447051/systematic-inequality/; see Robin Bleiweis, “Quick Facts About the Gender Wage Gap,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/03/24/482141/quick-facts-gender-wage-gap/.

[xxii] See John Podesta, et al., “A 100 Percent Clean Future,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/reports/2019/10/10/475605/100-percent-clean-future/.

[xxiii] Ruth Igielnik, “70% of Americans say U.S. economic system unfairly favors the powerful,” (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2020), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/01/09/70-of-americans-say-u-s-economic-system-unfairly-favors-the-powerful/.

[xxiv] See Todd Frankel, “A majority of the people arrested for Capitol riot had a history of financial trouble,” The Washington Post, February 10, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/02/10/capitol-insurrectionists-jenna-ryan-financial-problems/.

[xxv] Andy Green, Christian E. Weller, and Malkie Wall, “Corporate Governance and Workers,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/08/14/473095/corporate-governance-workers/; see also Brian R. Cheffins, “Corporate Governance and Countervailing Power,” The Business Lawyer (2018-19), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3225801.

[xxvi] David Madland and Malkie Wall, “The Middle Class Continues to Struggle as Union Density Remains Low,” (Washington: Center for American Progress Action Fund, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogressaction.org/issues/economy/news/2019/09/10/175024/middle-class-continues-struggle-union-density-remains-low/.

[xxvii] Marc Jarsulic, Brendan Duke, and Michael Madowitz, “Long-Termism or Lemons,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2015), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2015/10/21/123717/long-termism-or-lemons/; Green and Schwartz, “Corporate Long-Termism, Transparency, and the Public Interest,” supra.

[xxviii] Carmel Martin, Andy Green, and Brendan Duke, eds. “Raising Wages and Rebuilding Wealth,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2016), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2016/09/08/143585/raising-wages-and-rebuilding-wealth/.

[xxix] Ibid; see also CAP, Blueprint for the 21st Century; Green, Weller, and Wall, “Corporate Governance and Workers.”

[xxx] Gregg Gelzinis et al, “The Importance of Dodd-Frank, in 6 Charts,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2017), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2017/03/27/429256/importance-dodd-frank-6-charts/; Senator Jeff Merkley & Senator Carl Levin, “The Dodd-Frank Act Restrictions on Proprietary Trading and Conflicts of Interest: New Tools to Address Evolving Threats,” Harvard Journal on Legislation, Vol. 48 No. 2 (2013), available at https://harvardjol.com/archive/volume-48-number-2/; U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, “Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse,” Majority and Minority Staff Report, April 13, 2011, available at https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/PSI%20REPORT%20-%20Wall%20Street%20&%20the%20Financial%20Crisis-Anatomy%20of%20a%20Financial%20Collapse%20(FINAL%205-10-11).pdf.

[xxxi] See Council of Institutional Investors, Corporate Governance Policies 4 (updated Sept. 22, 2020), https://www.cii.org/files/policies/09_22_20_corp_gov_policies.pdf.

[xxxii] See Andy Green et al, “Letter to SEC on Corporate Transparency and Accountability and the Coronavirus Pandemic,” The FinReg Blog, May 26, 2020, available at https://sites.law.duke.edu/thefinregblog/2020/05/26/letter-to-sec-on-corporate-transparency-and-accountability-and-the-coronavirus-pandemic/; see also Andy Green, “Could the SEC secretly abolish investors’ right to sue?” Marketwatch, March 2, 2018, available at https://www.marketwatch.com/story/could-the-sec-secretly-abolish-investors-right-to-sue-2018-03-02#false.

[xxxiii] H.R. Rep. 73-85, at 3 (1933).

[xxxiv] SEC, What We Do, available at https://www.sec.gov/Article/whatwedo.html (as viewed Sept. 30, 2019) (subsequently removed).

[xxxv] Council of Institutional Investors, Press Release, SEC Muzzles the Voice of Investors by Raising the Bar on Shareholder Proposals (Sept. 23, 2020), https://www.cii.org/sept23_sec_muzzles.

[xxxvi] This section is based upon Andy Green, Gregg Gelzinis, and Alexandra Thornton, “Financial Markets and Regulators Are Still in the Dark on Climate Change,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/06/29/486893/financial-markets-regulators-still-dark-climate-change/. Additional resources include: Climate-Related Subcommittee of the Market Risk Advisory Committee, Commodity Futures Trading Commission “Managing Climate Risk in the U.S. Financial System,” (2020), https://www.cftc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/9-9-20%20Report%20of%20the%20Subcommittee%20on%20Climate-Related%20Market%20Risk%20-%20Managing%20Climate%20Risk%20in%20the%20U.S.%20Financial%20System%20for%20posting.pdf; Group of 30 Steering Committee and Working Group on Climate Change and Finance, “Mainstreaming the Transition to a Net Zero Economy” (Washington: Group of 30, 2020), available at https://group30.org/images/uploads/publications/G30_Mainstreaming_the_Transition_to_a_Net-Zero_Economy.pdf; Mark Carney, “The Road to Glasgow,” (London: Bank of England, 2020), available at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2020/the-road-to-glasgow-speech-by-mark-carney.pdf?la=en&hash=DCA8689207770DCBBB179CBADBE3296F7982FDF5; Glenn D. Rudebusch, “Climate Change Is a Source of Financial Risk,” (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2021), available at https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2021/february/climate-change-is-source-of-financial-risk/; Nahiomy Alvarez, Alessandro Cocco , Ketan B. Patel, “A New Framework for Assessing Climate Change Risk in Financial Markets,” (Chicago: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 2020) available at https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2020/448; Climate Safe Lending Network, “Taking the Carbon Out of Credit,” (London, 2020), available at https://www.climatesafelending.org/taking-the-carbon-out-of-credit; Global Financial Markets Association and Boston Consulting Group, “Climate Finance Markets and the Real Economy,” (Washington: SIFMA, 2020), available at https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Climate-Finance-Markets-and-the-Real-Economy.pdf.

[xxxvii] Willingham and Zonta, “A CRA To Meet the Climate Challenge,” supra.

[xxxviii] Graham Steele, “Confronting the ‘Climate Lehman Moment’: The Case for Macroprudential Climate Regulation,” 30 Cornell J.L.& Pub. Pol’y 109 (2020), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542840; see also Graham Steele, “The New Money Trust: How Large Money Managers Control Our Economy and What We Can Do About It,” (Washington: American Economic Liberties Project, 2020), available at https://www.economicliberties.us/our-work/new-money-trust/#.

[xxxix] See, e.g., Lael Brainard, “The Role of Financial Institutions in Tackling the Challenges of Climate Change,” (Washington: Federal Reserve Board, 2021), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20210218a.htm; Allison Lee, “Playing the Long Game: The Intersection of Climate Change Risk and Financial Regulation,” (Washington: Securities and Exchange Commission, 2020) available at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/lee-playing-long-game-110520; Rostin Behnam, “Changing Weather Patterns: Risk Management for Certain Uncertain Change,” (Washington: Commodity Futures Trading Commission, 2020) available at https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/SpeechesTestimony/opabehnam15; J. Robert Brown, Jr., “It’s Not What You Look at that Matters: It’s What You See, Revealing ESG in Critical Audit Matters,” (Washington: Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, 2020) available at https://pcaobus.org/news-events/speeches/speech-detail/it-s-not-what-you-look-at-that-matters-it-s-what-you-see-revealing-esg-in-critical-audit-matters.

[xl] See Gregg Gelzinis, “Bank Capital and the Coronavirus Crisis,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/05/16/469931/tailoring-banking-regulations-accelerate-next-crisis/; Gregg Gelzinis, “Tailoring Banking Regulations to Accelerate the Next Crisis,” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019) available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/05/16/469931/tailoring-banking-regulations-accelerate-next-crisis/.

[xli] See IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)], available at https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/.

[xlii] See Podesta et al, “A 100 Percent Clean Future,” supra; Rainforest Action Network, “Banking on Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Finance Report 2020” (San Francisco: 2020), p. 3, available at https://www.ran.org/bankingonclimatechange2020/; see also Tyler Gellasch and Andres Vinelli, “To address climate change, the SEC should require corporations to disclosure more information about their risks,” MarketWatch, Feb. 8, 2021, available at https://www.marketwatch.com/story/sec-must-force-corporations-to-disclose-more-to-address-climate-change-11612754449.

[xliii] James Mitchell, “The Poseidon Principles: A Groundbreaking New Formula for Navigating Decarbonization,” Rocky Mountain Institute, June 17, 2019, available at https://rmi.org/the-poseidon-principles-a-groundbreaking-new-formula-for-navigating-decarbonization/.