Courtesy of Lee Reiners and Joseph A. Smith Jr.

This case study draws primarily—and in some instances quotes verbatim—from the “Report on the Non-Resident Portfolio at Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch” prepared for the Bank on September 19, 2018, by the law firm Bruun & Hjejle.[1] Additional details are derived from other sources, including Danske Bank corporate reports and the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority’s “Report on the Danish FSA’s supervision of Danske Bank as regards the Estonia case.” This case study is intended to be used as a resource for directors at banks and financial services institutions of all sizes, so that they may learn from, and hopefully avoid, mistakes that were made in handling this matter. All errors are our own.

Danske Bank A/S (“Danske Bank” or the “Bank”) is the largest financial institution in Denmark, with operations in sixteen countries. As of December 31, 2017, the Bank had a total of 2.7 million personal customers, 211,000 small and medium-sized business customers, and 1,900 corporate and institutional customers.[2] The Bank’s primary supervisor is the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (DFSA) and the Bank’s operations within the European Union (EU) are subject to regulation and supervision by other national banking authorities.

Danske Bank has run into trouble resulting from alleged money laundering in its Estonian branch. Its board and management now face the daunting task of dealing with the Bank’s current difficulties.

Background

Danske Bank was organized in 1871 and has continuously operated since then. As of December 31, 2017, the Bank had total assets of $571 billion, shareholders’ equity of $25 billion, and net profit of $3.4 billion.[3] By contrast, Denmark’s 2017 GDP was just $329.9 billion.[4] The Bank is classified as a systemically important financial institution by Danish authorities.

Over time, Danske Bank extended the reach of its operations from its Danish base to the Nordic region and beyond. In addition to organic growth, the Bank increased its size and scope through mergers and acquisitions.[5] The source of the Bank’s current problems stem from its 2006 acquisition of Finnish-based Sampo Bank.

In 2017, the Bank reported income and profit by country of operation for that year and for 2016 as follows[6]:

| Country | 2017 Income

[DKK MM] |

2017 Profit before tax

[DKK MM] |

2016 Income

[DKK MM] |

2016 Profit before tax

[DKK MM]

|

| Denmark | 53,156 | 13,234 | 55,612 | 15,866 |

| Finland | 5,515 | 2,071 | 5,699 | 1,790 |

| Sweden | 4,447 | 5,402 | 5,104 | 4,332 |

| Norway | 7,595 | 2,717 | 7,134 | 1,629 |

| UK | 2,836 | 1419 | 2,828 | 1,304 |

| Ireland | 448 | 916 | 472 | 254 |

| Estonia | 197 | 52 | 286 | 120 |

| Latvia | 84 | 20 | 74 | -72 |

| Lithuania | 130 | -14 | 159 | -311 |

| Luxembourg | 808 | 170 | 739 | 113 |

| Russia | 188 | 70 | 178 | 67 |

| Germany | 116 | 56 | 166 | 128 |

| Poland | 107 | 59 | 94 | 57 |

| USA | 576 | 69 | 403 | 43 |

| India | 1 | 48 | 1 | 38 |

| Total | 76,203 | 26,288 | 78,949 | 25,357 |

Danske Bank’s Corporate Governance[7]

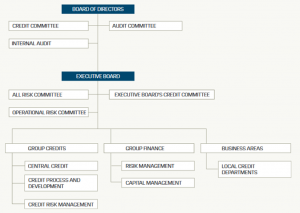

Danske Bank’s management structure reflects the statutory requirements governing listed Danish companies. The Board of Directors is entrusted with the overall and strategic management of Danske Bank, including responsibilities to monitor compliance and risk management. The Board defines overall limits for market risks and approves important elements of the risk management framework. Regular reporting enables the Board of Directors to monitor whether risk management policies and systems are complied with and match the Group’s needs. In addition, the Board of Directors reviews reports analyzing the Group’s portfolio during the year, particularly information about industry and sector concentrations.

From 2007 to 2017, the Board of Directors consisted of anywhere from eight to ten members elected to one-year terms at the general meeting and four to five employee representatives appointed for four-year terms. Under Danish law, employees are entitled to elect from among themselves a number of representatives equal to half of the number of members elected by the general meeting. Non-employee board members are not required to be independent. Committees of the Board of Directors include: the Nomination Committee, Credit Committee, Salary and Bonus Committee, and Audit Committee. The Audit Committee supervises external accounting and auditing but has no risk management responsibilities. Under Danish law, board committees do not have independent decision-making authority.

The Board of Directors appoints the Executive Board, which is responsible for the day-to-day management of the Bank and is chaired by the Chief Executive Officer. Its obligations include ensuring the Bank’s organizational structure is robust, transparent, and has effective lines of communication and reporting, including compliance and Anti-Money Laundering (AML). At the time of the Sampo Bank acquisition (November, 2006), the Executive Board had three committees that were in charge of ongoing risk management: the All Risk Committee, Credit Committee, and Operational Risk Committee.[8]

The All Risk Committee is responsible for the Group’s risk appetite process, capital and funding structure, and risk policies for relevant business areas. The Executive Board’s Credit Committee reviews credit applications that exceed the lending authorities of the business areas. It is also in charge of preparing operational credit policies and approving or rejecting credit applications involving issues of principle. The Operational Risk Committee is responsible for implementing a group-wide program that implements operational risk programs, processing reports from operational risk management functions, and handling “critical risks.”

Until it was disbanded upon the introduction of a new organizational structure in 2012, the Executive Committee, headed by the chairman of the Executive Board, was a larger body— compared to the Executive Board—that constituted the Group’s day-to-day executive management and functioned as a coordinating forum.[9] Its objective was to take an overall view of activities across the Group, focusing on the collaboration between support functions and product suppliers on the one hand, and individual units and country organizations on the other.

Questions for Directors

- Given Danske Bank’s corporate governance structure, are the lines of authority clear to you? Why or why not?

- If you were offered a position on the Danske Bank Board of Directors, how would you prepare yourself to exercise a director’s oversight responsibilities generally and with regard to risk management and compliance in particular?

- Does the international scope of operations create any concerns for you? Would you assume that some of the international operations are immaterial to the Bank as a whole? If so, would that affect your oversight of such operations?

- How would the membership of four or five employees affect your decision to join the Board of Directors? What would you expect from them in terms of competencies? What concerns would you have?

Danske Bank at Year-End 2017

In its 2017 Annual Report, Danske Bank, in the section titled Strategy Execution, describes itself as, “a Nordic universal bank with strong local roots and bridges to the rest of the world.”[10] The Annual Report goes on to discuss four strategic themes: (i) Nordic potential; (ii) Innovation and digitalization; (iii) Customer experience; and (iv) People and culture. The Bank’s “Nordic potential” lies in capturing market share outside of Denmark: “With total market shares of around 6% in Sweden and Norway and 10% in Finland, our Nordic strategy holds considerable potential for future growth.”[11]

The generally optimistic tone of Strategy Execution is dampened by an additional subsection that is not included in the four “strategic themes” mentioned above: Compliance.[12] While this subsection begins with a reference to compliance culture, it ends with a series of disturbing disclosures regarding allegations of money laundering in the Estonian branch. The first disclosure is that the Bank has commenced an internal investigation of such activity between 2007 and 2015. The second is of a formal investigation of the Bank by French authorities relating to alleged money laundering in Estonia between 2008 and 2011. The final disclosure is a fine of DKK 12.5 million levied by the Danish Public Prosecutor for Serious Economic International Crime for violating Danish anti-money laundering legislation on the monitoring of transactions to and from correspondent banks.

The underlying problems referenced by these disclosures originated in Danske Bank’s 2006 acquisition of Sampo Bank.

The Sampo Acquisition

On November 9, 2006, Danske Bank announced its agreement to acquire Sampo Bank, “the third largest bank in Finland with an extensive branch network, subsidiaries in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and a recently acquired bank in Russia.”[13] The price was just above EUR 4 billion, with a little more than half allocated to goodwill in Danske Bank’s subsequent annual report for 2006.[14] Upon completion of the acquisition on February 1, 2007, Ilkka Hallavo, head of Sampo Bank in Finland, and Georg Schubiger, head of Sampo Bank in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, joined the Executive Committee.[15]

In addition to the activities in Finland, Sampo Bank had three smaller subsidiaries in the Baltic region: AS Sampo Pank in Estonia, AB Sampo Bankas in Lithuania and AS Sampo Banka in Latvia.

Sampo Pank in Estonia traces its origins to two Estonian banking entities—Eesti Forekspank and Eesti Investeerimispank—established in 1992, in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. At the time, there were strong economic ties between Estonia and the Russian Federation. Both Eesti Forekspank and Eesti Investeerimispank were taken over by the Estonian Central Bank after coming under stress during the Russian ruble crisis in 1998. The banks were combined to form Optiva Pank—the third largest bank in Estonia—which was then purchased by Finnish-based Sampo Bank in 2000.[16]

Sampo Bank significantly grew their operations in the Baltics prior to the Danske Bank acquisition. At year-end 2003, Sampo Pank (the Estonian bank) had 13 branches and 90,000 customers.[17] By year-end 2006, these figures had grown to 19 branches and 143,000 customers (11% of Estonia’s population).[18] Most of the increase came from new retail customers.

With this growth came increased profitability. Return on equity for Sampo Pank was 23 percent in 2005, 26 percent in 2006 and 30 percent in 2007.[19]

Sampo Pank grew to become Estonia’s third-largest bank, and in 2006, Sampo Bank entered the Russian market for the first time, by acquiring Industry and Finance Bank (Profibank), a small bank based in St. Petersburg. Profibank was included in the Danske acquisition and has since been merged into Danske Russia.

Despite Sampo Bank’s rapid growth in the Baltics, there is no indication their risk management grew concomitantly. Sampo Bank was confident that this growth posed no risks, as evidenced by the fact that in 2005 and 2006, they took no legal reserves, as “professional advice indicates that it is unlikely that any significant loss will arise.”[20]

Danske Bank was enticed by Sampo Bank’s geographic diversity, as evidenced by the CEO’s remarks upon announcing the acquisition:

Our investment in Finland is in line with the Group’s strategy of expanding its retail banking activities in Northern Europe … Our joint banking concept – the Danske Banking Concept – provides a sound platform for expansion. Sampo Bank is attractive because its retail banking profile and structure match ours and support our strategy of further geographical and risk diversification. Another advantage is that economic growth in Finland and in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania exceeds the EU average. That provides an excellent basis for continuing growth.[21]

Prior to 2007, Danske Bank had no presence in the Baltics.[22] Bank management made clear in presentations at the time of the acquisition, that expansion would bring significant increases in the population of markets served (57%), customers (44%), and branches (22%).[23] On a pro forma basis, Sampo Bank accounted for 7% of assets, 12% of deposits and 13% of profits before taxes.[24] The transaction was expected to generate savings by integrating Sampo Bank into Danske Bank’s IT platform.[25] However, these integration plans did not extend to Sampo’s Baltic subsidiaries. According to the Bank’s public statement announcing the acquisition:

Danske Bank expects to complete the integration of Sampo Bank’s Finnish activities into Danske Bank’s IT platform at Easter 2008. It has not been decided when to integrate the IT systems of the still relatively small operations in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Russia.[26]

Danske Bank noted in their 2007 annual report that the three Baltic banks will migrate to the Group’s IT platform in the course of 2009, and that the Baltic banks will see extensive large-scale training activities for all 1,300 staff members.[27]

Questions for Directors

- What risk factors should management and the Board have considered before going ahead with the Sampo acquisition?

- How important is integration of Sampo operations into Danske Bank? Is it realistic to think such integration is achievable in the near-term?

- What steps should have been required to insure successful integration generally, and adequate risk management in particular?

Danske Bank’s Risk Management at the time of the Sampo Bank Acquisition

The source of Danske’s current problem lies in the Estonian branch’s Non-Resident Portfolio. The Non-Resident Portfolio refers to the former pool of non-resident customers managed within the Estonian branch by a designated group of employees (relationship managers and others). Customers in the Non-Resident Portfolio were both private persons and corporate entities and the services offered to these customers include payments and other transactions in various currencies, foreign exchange lines (“FX lines”) and bond and securities trading (only very limited credit facilities were offered to customers in the Non-Resident Portfolio).

When Danske’s acquisition of Sampo Bank took effect on February 1, 2007, the International Banking department within the Estonian branch managed the Non-Resident Portfolio. In May 2007, this department was integrated into the Private Banking Department within the Personal and Retail Banking division, which handled both resident and non-resident customers. However, Danske Bank had no way of knowing how many customers constituted the Non-Resident Portfolio because no customer lists were kept until 2013.

At the time of the acquisition, it was clear that the Estonian financial system was growing increasingly reliant on non-resident customers. According to publicly available data from Estonia’s central bank, total non-resident deposits in Estonian banks was EUR 284.5 million at the start of 2000. By year-end 2007, this figure had grown to EUR 1.59 billion and would eventually peak at EUR 2.95 billion on June 30, 2015.[28]

Sampo Pank continued to operate as a standalone subsidiary following the acquisition and in June 2008, became a branch of Danske Bank (its name was officially changed to Danske Bank in November 2012). The Estonian branch had its own Executive Committee and the Branch manager reported directly to the head of Baltic Banking. From 2007 to 2009, the head of Baltic Banking reported directly to Danske Bank’s CEO. In addition, there was a joint board of directors for the Baltic entities, the Baltic Advisory Board (earlier named the Baltic Supervisory Board) with members from Group, as well as a Baltic Executive Committee.

Danske Bank employs a standard “three-lines-of-defense” model for risk management. The first line of defense consists of risk management exercised by the business areas. They enter the necessary registrations about customers that are used in risk management tools and models, and they maintain and follow up on customer relationships. Each business area is responsible for preparing carefully drafted documentation before business transactions are undertaken and for properly recording the transaction. Each business area is also required to update information on customer relations and other issues as may be necessary. The business areas must make sure that all risk exposure complies with approved risk policies as well as the Group’s other guidelines. Historically, the business areas have exclusively focused on credit risk.

The second line of defense is performed by the risk, compliance, and AML functions, which oversee, monitor, and challenge the risk exposures of the Bank’s business units and are responsible for implementation of efficient risk management and compliance procedures. However, at the time of the Sampo Bank acquisition, these functions were scattered across various departments. For instance, Group Credits had overall responsibility for the credit process in all of the Group’s business areas. This included the responsibility for developing rating and scoring models and for applying them in day-to-day credit processing in the local units. Group Finance oversaw the Group’s financial reporting and strategic business analysis, including the performance and analytic tools used by the business units. The department was also in charge of the Group’s investor relations, corporate governance, capital structure, M&A, and relations with rating agencies. Risk Management was also part of Group Finance. As the Group’s risk monitoring unit, Risk Management had overall responsibility for the Group’s implementation of the rules of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), risk models, and risk analysis.

Finally, the third line of defense lies with functions that provide independent assurance and assessments (above all, Group Internal Audit).

Questions for Directors

- Would you have any concerns around Danske Bank’s risk management structure?

- How does Sampo Bank generally, and its Estonian operation in particular, fit into the Danske Bank risk management structure?

- Given the growth in the scale of the Bank’s operations, is the emphasis on credit risk appropriate?

- Do the answers to any of the foregoing questions change depending upon whether you are an employee-designated member of the Executive Board or an “independent” director? If so, how?

Initial Signs of Problems in Estonia

In the spring 2007, the Estonian FSA (EFSA) carried out an inspection at Sampo Pank in Estonia, focusing on the bank’s non-resident customers. The division of responsibilities between the Danish FSA (DFSA) and the EFSA with regard to Danske Bank’s branch in Estonia follows from EU legislation. As the host country supervisor, the EFSA is responsible for the AML supervision of the Estonian branch. Suspicious transactions and activities must be reported to the Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit[29] (“FIU”) who then forwards them to the police and other authorities for further investigation and prosecution. As the home country supervisor of Danske Bank, the DFSA is responsible for monitoring that the Group has sufficient capital and liquidity, and for supervising the Group’s overall governance of its activities. The DFSA is also responsible for the AML supervision of Danske Bank’s Danish activities.

The EFSA’s final inspection report, written in Estonian, was issued on August 16, 2007. On September 20, 2007, the branch sent an English translation of the report’s summary to Danske Bank’s Group Compliance & AML in Copenhagen, which shared it with Group Legal.

The EFSA found deficiencies with respect to KYC (Know Your Customer) information, writing that: “the Bank’s routine practice has not been fully in compliance with the requirements stipulated in valid legal acts and international standards.” The EFSA concluded that “the Bank has underestimated potential risks, associated with providing services to legal entities registered in a low-tax area and undue compliance with relevant procedure rules.” As for non-resident customers in particular, the EFSA stressed the “additional risks” involved, and found that “the actual activity of the Non-Resident Customers Department aimed at examining the activities of clients is not in compliance with international practice and is not sufficient, regarding the specifics of the activities of this particular client group and associated risks.” The EFSA informed the DFSA about their exam findings but, it is unclear if, or how, the DFSA acted on this information.[30] In December, the Estonian branch informed the EFSA of actions taken to comply with the exam findings and orders. Danske Bank’s Board of Directors did not receive any information related to the EFSA exam.

In June 2007, the DFSA received a letter from the Central Bank of Russia expressing concern over the non-resident customers of Sampo Pank in Estonia. The letter noted that “clients of Sampo Bank permanently participate in financial transactions of doubtful origin” estimated at “billions of rubles monthly.” After a description of a type of transaction, the Russian Central Bank further stated that “the mentioned transactions can be aimed at tax and custom payments evasion while importing the goods, or giving the legal form to the outflow of the capital, or they can be connected with the criminal activity in its pure form, including money laundering.” On June 18, 2007, the DFSA forwarded this letter to the Executive Board of Danske Bank and asked Danske Bank for a report that addressed its contents.

The DFSA discussed the matter with Danske Bank’s Head of the Legal department (who was also the person responsible for AML) and the Bank’s Chief Audit Executive. The feedback received from both was that there were no problems in relation to AML risks in the Estonian branch. Group Legal and Group Compliance & AML then replied to the DFSA on behalf of the Bank, by letter, on August 27, 2007. The letter made reference to the recent inspection report from the EFSA, noting that the EFSA’s “conclusion of the inspection was that the bank complies with the existing laws and regulations” and that the EFSA had had no “material observations.” The Board of Directors never received the letter.

The DFSA convened a meeting with Danske Bank on September 3, 2007, at which Group Legal provided equally comforting information. The DFSA also talked with Group Internal Audit, which informed the DFSA that local internal auditors with Sampo Pank in Estonia had looked more closely into the issues raised by the Russian Central Bank and found nothing of note. The DFSA informed the EFSA of this feedback.

The letter from the Russian Central Bank was on the August agenda for the Executive Board and Board of Directors meetings. At these meetings, information was given that the matter would be investigated internally, and the Board of Directors left it with the Executive Board and Group Internal Audit to come back if there were any negative findings. The Board of Directors never received any additional updates on the matter.

Questions for Directors

- Would the failure by management to fully inform and update the Board of directors be acceptable to you as a director? Could you take the view that the Estonian branch is immaterial to Danske Bank as a whole?

- Once aware of the regulatory criticism, what would you as a member of the Executive Board require from management?

- Is knowledge of the international scheme of bank regulation a critical competence of Danske Bank directors? If not, how is compliance to be overseen and assessed?

2008 – 2010

In 2008, Sampo Pank in Estonia was converted into a branch of Danske Bank—as was originally planned at the time of the Sampo Bank acquisition—however, plans to integrate the newly acquired Baltic subsidiaries onto the Group IT platform were shelved after the Global Financial Crisis hit and it was deemed too expensive. Danske Bank’s management recognized that cancelling the IT migration required additional focus on compliance in the Baltic operations, and later in 2008, Group Internal Audit reviewed the AML procedures in the Estonian branch and gave a rating of “satisfactory” (the second best rating). It was observed that “[t]he non-resident customers department has improved considerably in applying KYC [Know Your Customer] principles” although Group Internal Audit also noted “a few shortcomings.” Group Compliance & AML continued to find no issues arising from AML in the Estonian branch throughout 2009.

In January 2008, EU Directive 2005/60 (“Third AML Directive”) was implemented into Estonian law in the form of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Prevention Act (MLTFPA). Pursuant to this regulation, financial institutions had to perform customer due diligence, e.g. when establishing a business relationship with a customer or when there was a suspicion of money laundering (or terrorist financing), regardless of any derogation, exemption or threshold. The customer due diligence measures included an obligation to establish the customer’s identity (and, where applicable, the beneficial owner) and to obtain information on the purpose and intended nature of the business relationship. Financial institutions had an obligation to conduct enhanced customer due diligence in situations which by their nature presented a higher risk of money laundering (or terrorist financing).

Yet another important part of the regulation consisted in reporting obligations. If a financial institution knew of, suspected, or had reasonable grounds to suspect a customer of engaging in money laundering (or terrorist financing), this had to be reported to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), in the form of a suspicious activity report (SAR).

These new guidelines were incorporated into the EFSA’s follow-up AML inspection from 2007.

In October 2009, the Estonian branch provided Group Compliance & AML with an English summary of the final inspection report. According to the summary, the EFSA found the attitude of branch employees concerning the objectives of and compliance with statutory requirements had “improved considerably.” The EFSA also found that the branch had “changed or updated its internal procedures in line with the legal amendments made in 2008” (albeit with “some deficiencies”). The EFSA worryingly noted that “[t]he documents and information about customers and their activities reviewed in the course of the on-site inspection did not comply with the requirements of legislation and/or the internal procedures of the Branch in all cases.” They stressed “the importance of obtaining the relevant information, especially about the beneficial owners, ownership and control structures and economic activities of customers in order to guarantee that the Branch and the entire financial system of Estonia function in a manner that is trustworthy and in compliance with international standards.” The Board of Directors never received information pertaining to the inspection report.

In 2010, news reports linked several Estonian branch customers to illegal activities. In January, Barron’s published an article linking a specific company, which was a customer of the branch, to a North Korean arms smuggling case in Thailand (the article did not mention Sampo Pank or Danske Bank). Action was taken within the Estonian branch to address the situation but the Group was not informed.

On January 25, 2010, Estonian media linked the Estonian branch to an alleged money-laundering scheme involving a currency exchange company and a specific customer. On January 28, 2010, this story was, in short form, reflected in Danish media when another Danish bank stated that the matter related to Sampo Pank. This gave rise to questions at Group level, and the matter came up again in March 2010 among members of the Executive Board following approach by one of Danske Bank’s correspondent banks.

These news reports prompted the Executive Board to take note of the Non-Resident Portfolio in the Estonian branch. Thomas Borgen, who joined the Executive Board in September 2009 and was responsible for Baltic banking activities until June 2012, told his colleagues in an email that expansion in Estonia should not come at the cost of AML violations.

At an Executive Board meeting in March 2010, there was a discussion around the number of suspicious activity reports (“SARs”) filed by the Estonian branch. The discussion is reflected in the minutes as follows (translation):

The AML report states at page 5 that Estonia accounts for a 30 % market share of the “Suspicious Activity Reports.” According to [name], the reason for this high share is that the standard of Danske Bank is high compared to other banks in Estonia.

Concerns were also expressed over the number of Russian transfers in the branch, to which Borgen noted that the Russian Central Bank had been contacted, and it had agreed to these transfers. Borgen indicated he had not come across anything that could give rise to concern.

Borgen brought up the Non-Resident Portfolio again at the Executive Board’s September 2010 meeting. According to the minutes, other employees told Borgen they were:

Comfortable with the situation in Estonia with substantial Russian deposits. This was also underlined by the approval received from the Russian Central Bank to establish a representative office in Moscow.

Questions for Directors

- As a Danske Bank Board member, would you have accepted the “too expensive” rationale for operating Sampo under a separate IT system?

- Given the disclosure of damaging information by sources outside the Bank (e.g., the press) should Danske Bank’s Board of Directors have commissioned independent investigation and monitoring of the Baltic operations? What are the plusses and minuses of this approach?

- Does the fact that the Baltic operations’ returns related more to transactions (flow of funds) and less to loans (balance sheet items) make a difference in the oversight approach management and the Board should take?

- What should the Board of Directors role be whenever a significant new regulation is implemented in a country the firm operates in?

2011 – 2012

The Estonian branch remained largely out of sight for the Board of Directors throughout 2011, aside from a board meeting in May in which the branch’s high profitability was discussed (it was noted that the return on equity (“ROE”) before loan losses for the Estonian branch had increased from 45 % in 2007 to 58 % in 2010). According to minutes of the meeting, the board agreed that “it was important to focus on the right customers” and that “[t]he short-term target was not to be number one or two, but the Bank had to have ambitious goals for the long term.”

2012 brought a renewed focus on AML throughout Danske Bank and at the Estonian branch in particular.

In February 2012, the DFSA received another letter from the EFSA regarding “a number of serious AML/CFT issues in the Estonian branch.” The EFSA noted “[t]he relatively big concentration of the business relationships from risk countries in Branch is not accidental” and that “the same risk patterns” had been identified by the EFSA during its inspections in 2007 and 2009. The DFSA presented this letter to Group Compliance & AML at Danske Bank and requested an explanation for the lack of action taken by the branch.

When replying to the DFSA several weeks later, Group Legal and Group Compliance & AML relied upon information supplied by the Estonian branch. It was stated that “[i]n order to mitigate the risk of being used for money laundering or terror financing Sampo Pank Estonia operates a determined control environment regarding customer relation establishment and transaction monitoring.” The letter also stated that the shortcomings identified by the EFSA in their 2009 inspection report had been corrected and that the Bank is “fully aware that the customer database of Sampo Pank Estonia includes a number of high risk customers. However, we are confident that the control setup corresponds to the actual risk.”

Group Compliance & AML visited the Estonian branch in May, and the findings from this visit were reflected in an appendix to the report from Group Compliance & AML for the first half of 2012. As for the Estonian branch, focus had been on “the ongoing process of controls to ensure that rules are complied with” and “screening of outgoing payments against EU/UN and OFAC list [US Office of Foreign Assets Control’s sanction list].” It was added that “[a]s of today incoming payments are not screened and this might be one of the focus areas going forward.”

In June 2012, Danske Bank’s Baltic banking activities were placed under the Group business unit “Business Banking.” This marked the third time in five years that the line of business reporting structure for the Estonian branch had changed.

Figure 1: Estonian branch line of business reporting structure

A few months after its establishment, the credit and risk function within Business Banking became aware that use of foreign exchange lines (FX lines) in the Estonian branch fell outside Group credit policy because they were used by non-resident customers, some of whom lacked financial statements. It was pointed out that these were high-risk customers, and concerns were raised regarding AML. Ultimately, the use of FX lines was made subject to a memorandum that was approved by two members of the Executive Board as well as other employees at Group level, and which noted:

The paramount risk in these arrangements relate to the banks reputation. Today risk mitigation is achieved by screening customers using the KYC process. The process was presented to the local and DFSA and is more comprehensive than what is currently being used in other business areas.

In June 2012, the DFSA issued nine orders and four pieces of risk information related to an exam of AML risks in Danske Bank’s Danish activities that was conducted in 2011. The orders covered a broad field and included KYC procedures, correspondent banking, transaction monitoring and training programs. Danske Bank’s Board of Directors reviewed the orders and expressed an ambition to become “Best in Class” within AML. At a follow-up inspection in November 2012, the DFSA found that Danske Bank had satisfactorily addressed all orders.

Around this same time, Danske Bank was attempting to open a New York Branch which required approval by the New York Federal Reserve. As part of their New York branch application, the Bank produced an AML action plan which was presented to the Board of Directors at their September meeting. The board rejected the plan because “the AML issues had been known for a long time, actually several years” and they were not comfortable with issuing a declaration to the Federal Reserve about the AML issues “at the present stage.”

On November 30, 2012, Group Internal Audit issued a report on AML in the Estonian branch with an overall rating of “extensive” (the best possible rating). The report included no recommendations for improvement.

At the end of 2012, Danske Bank’s AML responsible person retired. From the end of 2012 to November 2013, Danske Bank did not have a person responsible for AML activities as required by the Danish Anti-Money Laundering Act. The DFSA was not notified of this until February 2018. The Board of Directors and the Executive Board have stated that in practice, the head of Group Compliance & AML, who reported to the Bank’s CFO, was the person responsible for AML activities.

Questions for Directors

- Should board members be concerned when there are frequent changes to reporting structures?

- How would you assess the performance of Danske Bank’s Board in ensuring the firm achieved the Board’s desire to be “Best in Class” with regard to BSA / AML?

- Are the returns from the Baltics noted above “too good to be true”? How should the Executive Board and the Board of Directors react to such returns?

2013

In the spring of 2013, the EFSA contacted the DFSA based upon a warning received from the Russian Central Bank about a list of Danske’s “Russian customers who were blacklisted.” The DFSA contacted the Bank, and the acting Head of the Legal Department replied that the branch had a special setup in light of the elevated AML risk in the Estonian branch.

On April 7, 2013, Group Compliance & AML contacted branch management, referring to “our blacklisted Russian customers.” They noted that “the Danish FSA is now very worried because they have confirmed to the US authorities that we comply with Danish FSA’s requirements on AML,” and “[i]t is critical for the Bank that we do not get any problems based on this issue. We cannot risk any new orders in the AML area.”

In June 2013, a member of the Executive Board was contacted by one of the correspondent banks used by the Estonian branch to clear USD payments. The correspondent bank expressed concern over AML issues in the branch which led a small group within Business Banking to review the Non-Resident Russian profiles within the branch. Ultimately, and in agreement with the correspondent bank in question, the Estonian branch sent a closure notification terminating the correspondent banking relationship, effective August 1, 2013. Following the termination, another correspondent bank expanded its USD clearing business with the Estonian branch.

The termination of the USD correspondent banking relationship prompted the Executive Board to launch a business review of the Non-Resident Portfolio. As part of this review, Business Banking noted that “over-normal profit is usually a warning sign, superior service or not,” and concern was expressed that “the lack of price-sensitivity with some customers is due to other factors than good service.” For its part, Group Compliance & AML stated that “the business volume (transactions) with non-resident customers in Estonia” was larger than expected. Also, the presence of so-called intermediaries, in the form of “non-regulated entities,” was questioned. Intermediaries constituted a small group of customers in the Non-Resident Portfolio holding accounts for the purpose of facilitating transactions with their own end-customers outside the branch.

The Bank underwent a significant management change while the business review was ongoing. On September 16, 2013, the Board of Directors appointed Thomas Borgen as new Chief Executive Officer, replacing Eivind Kolding, who resigned immediately. Previously, Borgen had been a member of the Executive Board responsible for Corporate & Institutional Banking—which oversaw Baltic banking—and these areas continued to be a part of his responsibilities until a replacement was appointed in November. At the time of Borgen’s promotion, the Chairman of the Board of Directors, Ole Andersen, said:

Thomas F. Borgen is an experienced and customer-oriented banker, who knows how to run a modern bank. The Board of Directors knows Thomas as an open and modern leader with a strong focus on goal-oriented execution in close collaboration with the Board of Directors, the executive management and the employees. Thomas is well positioned to make a significant contribution to a renewal of the Bank’s management culture so that the Bank becomes more open, result-oriented and even more focused on the customers.[31]

On October 16, 2013, both the full presentation on the business review and a summary were forwarded to Business Banking. The presentation stated that intermediaries would be “harvested” and subject to a “[r]un-off,” and that the business segment would follow a strategy to “focus on preserving client quality not on acquiring new clients.” When forwarding the presentation, Baltic Banking noted, among other points, that “[t]he business line is profitable and contributing significantly to Baltic Banking performance,” and that “[t]here are resilient KYC and AML procedures in place” and “no pending discussions on business with regulators.”

Around the time the business review was concluding, employees within the Estonian branch were brainstorming ways to assist non-resident customers with their payment needs. On October 15, a memorandum titled “Solutions in the Non-resident Intermediaries customer segment using bonds” (the “OFZ memo,” OFZ being Russian government bonds) was circulated to the branch’s Executive Committee. The memorandum presented “a solution for ten customers in our Non-resident Intermediaries segment using bonds as a faster, cheaper and more reliable way for their end-clients to transfer money overseas than making an international payment through a domestic Russian bank.” It was added that “the solution” was “highly profitable,” but also that “[c]onsistent with our strategy for the segment, we do not add new Intermediary clients and expect the number of clients in the segment to decline over time.” Two main risks were indicated: (i) “We do not have full knowledge about the end-clients of the Intermediary,” and (ii) “[t]here is potential reputational risk in being seen to be assisting ’capital flight’ from Russia.” With regard to the first main risk, an earlier draft had added: “and therefore potentially this solution could be used for money-laundering,” but these words had been left out in the final version at the initiative of a member of branch management.

This memorandum was shared with two members of the Executive Board but not the CEO. However, the CEO did discuss the Non-Resident Portfolio with three other Executive Board members in late October at a Business Banking Performance Review Meeting. According to the minutes, the “initial take” presented by a member of the Executive Board was “that the size of Danske Bank business undertaken with this category of customer is larger than DB peers, and the proportion of business needed to be reviewed and potentially reduced.” The CEO responded by emphasizing “the need for a middle ground” and that the issue should be discussed “further outside of this forum.” A member of the Executive Board “agreed to hold a meeting when Business Banking had finalised its conclusions.” No such follow-up occurred.

The year ended with an explosive revelation that would prove a crucial turning point in the ongoing AML saga at the Estonian Branch. In December 2013, the Head of the Markets Department in the branch (hereinafter “the whistleblower”) contacted a member of the Executive Board as well as employees from Baltic Banking, Group Compliance & AML and Group Internal Audit about potential money laundering in the Estonian branch’s International Banking Department. The report was titled “Whistleblowing disclosure – knowingly dealing with criminals in Estonia Branch” and it included the following information about a specific customer:

- The Estonian branch did not have financial data on the specific customer, and the customer had filed false financial accounts with the UK Companies House.

- The Bank knowingly continued to deal with a company that had committed a crime.

- After the whistleblower had brought up within the branch the question of false financial accounts, “[a]n employee of the bank cooperated with the company to fix the ‘error’,” whereby new financial accounts had been filed, which were equally false.

- The customer remained with the branch, and “[t]he bank continued dealing with the company even after it had committed another crime by submitting amended false accounts.”

- In September 2013, it was decided to close all accounts held by the customer in question as well as by “other members of the influence group.” This was decided as a result of suspicious payments, insufficient knowledge of beneficial owners (according to the whistleblower, “apparently it was discovered that they included the Putin family and the FSB,” that is the Russian Federal Security Service), and also due to the beneficial owners having “been involved with several Russian banks that had been closed down in recent years.”

- In conclusion, the whistleblower shared their views on “what looks wrong here,” stating that “[t]his should all be seen in the context of the high-risk nature of the international business in Estonia (that is supposed to be well-recognised and addressed by local management), that UK LLPs [Limited Liability Partnerships] are the preferred vehicle for non-resident clients (so should be well understood) and that the control environment is supposed to be ‘comprehensive’.”

Questions for Directors

- Was the Board of Directors too reliant on information supplied by the Estonian branch to assess the firm’s performance in remediating AML issues? Why or why not?

- Given the ongoing developments, what more could, and should, the Executive Board and Board of Directors have done to address issues relating to the Estonian operation?

- How should the Executive Board and Board of Directors have responded to the whistleblower allegations?

2014

It was quickly decided among the four recipients of the whistleblower report that Group Internal Audit should conduct an investigation into the allegations, using employees from outside the Estonian branch. On January 7, 2014, the Executive Board was informed of the allegations but was not given a copy of the whistleblower report. The Audit Committee was also given information about the investigation by Group Internal Audit at its meeting on January 27, 2014. However, according to minutes of the meeting, it was not specified that the investigation resulted from a whistleblower report.

On January 9, 2014, three more customers with “similar irregularities” were reported to Group Internal Audit by the whistleblower. In March and April 2014, there were additional reports from the whistleblower, including concerns about customers structured as Danish limited partnership companies (“K/S companies”). In its Corporate Responsibility report from 2013 (released in February 2014), Danske Bank wrote:

[Whistleblower] [R]eports are passed on to the Group Chief Auditor, the Group General Counsel and the Board of Directors’ Audit Committee for further action. In 2013, four cases were reported through the whistleblower system. They occurred both in and outside Denmark. Three cases that were concluded led to changes in procedures or increased management attention. One case is still under investigation.

In a January letter to the Executive Board, Group Internal Audit confirmed some of the allegations made by the whistleblower. Documents provided by some customers when opening accounts were found to be insufficient. Group Internal Audit also pointed to the potential risk of a customer having been “tipped off” (implying that the customers had been colluding with employees at the Estonian branch). More generally, it was noted that “ongoing monitoring” was performed manually by account managers, who were responsible for so many customers that it was “in fact impossible to perform the monitoring in an effective and efficient way.” It was added that “[b]ased on the work performed, we have not identified areas that need immediate reporting to the FSA.”

In early February 2014, Group Internal Audit conducted an on-site audit at the Estonian branch. Auditors were provided with the OFZ memo on intermediaries from October 2013. On February 5, 2014, Group Internal Audit presented its draft conclusions in an email forwarded to two members of the Executive Board and in turn shared with other members, including the CEO. It was stated that: “we cannot identify actual source of funds or beneficial owners” and that an employee with the branch had “confirmed verbally (in the presence of all 3 auditors …) that the reason underlying beneficial owners are not identified is that it could cause problems for clients if Russian authorities requests information.” Moreover, it was stated that “[t]he branch has entered into highly profitable agreements with a range of Russian intermediaries where underlying clients are unknown.” As part of the overall conclusions, Group Internal Audit recommended “a full independent review of all non-resident customers.”

When informed of Group Internal Audit’s findings via email, the CEO responded: “Noted. Here you should consider an immediate stop of all new business and a controlled winding-down of all existing business.”

A working group was established to address the findings of the February audit report. The working group consisted of two members of the Executive Board as well as members from Business Banking, Baltic Banking, Group Compliance & AML and Group Internal Audit. At its first meeting on 7 February 2014, the working group defined six action points:

- “Close for all new off-shore customers, pending an independent review of the business area

- Close all business with intermediaries immediately

- Draft terms for an external second opinion on the adequacy of and compliance with the KYC procedures and systems in Estonia

- Review identified files

- Consider any HR actions to be taken

- Clarify responsibility for escalation of whistle blower findings to relevant FSA – or other authority”

These action points were dealt with in subsequent meetings.

Following up on its audits letters from January and February, Group Internal Audit issued an audit report on March 10, 2014 that addressed the Estonian branch’s non-resident customers (this report was shared with the Estonian branch). The report assigned the worst possible rating of “Action needed” and noted that “[t]he Branch’s portfolio of nonresident customers has to be reviewed and information on the commercial rationale for the customers structuring their business within LLP layers as well as on the ultimate beneficial owners of the trading entities underlying the LLPs have to be sufficiently documented in the Bank systems”

The working group instructed Group Compliance & AML to engage an external consultancy to evaluate internal AML procedures and controls at the Estonian branch. The consultancy provided a draft report on March 31, 2014, and a final report on April 16, 2014, both of which were sent to Group Compliance & AML and shared with some members of the Executive Board. In connection with its draft report, the consultancy wrote that “[b]ased on our experience in conducting such engagements, you do not have as many low impact issues as some of your peers, but your critical gaps (e.g. regarding risk assignment, transaction monitoring, level of CDD [Customer Due Diligence] applied) are greater than we’ve seen in other banks in the region.” In response to a question on whether there had been breaches of AML regulation, the consultancy confined itself to general remarks and a statement to the effect that “[c]ertain specific local legislation gaps do however exist.”

In the final report, the external consultancy found that procedures for accepting new clients and opening new accounts for non-resident customers were overall followed. However, the report also noted shortcomings in relation to unclear instructions for account agreements and KYC questionnaires, as well as insufficient monitoring of transactions. The report identified 17 “control deficiencies” that all were assessed as critical or significant. The Estonian branch worked throughout 2014 to close these gaps.

In April 2014, the Estonian branch initiated a new review into corporate customers in the Non-Resident Portfolio. The review was overseen by Baltic Banking and the newly established Group business unit, International Banking. As part of this review, relationship managers with the branch completed separate memos for each of the nonresident business customers for whom they were responsible. The memos were reviewed by a committee at the branch in which members of branch management took part. It was for the committee to decide whether customer relationships were allowed to be carried on or should be terminated.

Information about the Estonian branch and the whistleblower case was presented to the Executive Board and the Board of Directors at their April meetings. The Executive Board was given a presentation by a fellow member titled “Status Danske Bank Estonia Branch.” The presentation, which had been prepared by employees within Business Banking, contained three slides titled: “Timeline for Whistleblower Case and Audit Reports.” The slides listed some of the whistleblower allegations as well as findings by Group Internal Audit and the external consultancy. According to minutes of the meeting, the Executive Board was told that “the appropriate steps were being taken to continue dealing with the matter in accordance with the Group’s whistle blowing policy, as well as all the applicable local regulations and supervisory rules.” The Executive Board was informed of the ongoing customer review, which would include an assessment of “how the business could be exited in an appropriate fashion.” During the meeting, the CEO instructed Group Compliance & AML to prepare a new plan for AML in the Baltics, which was eventually approved on August 1, 2014.

At the end of April, the Audit Committee reviewed the draft status report for Q1 2014 prepared by Group Internal Audit. During the meeting, Group Internal Audit informed the committee that “the local internal auditor was under surveillance” and that “[t]he Bank’s best practice [at Group level] was different from the local Estonian practice, and the local internal auditor had not followed the procedures as he should have.” The next day, the Board of Directors discussed the whistleblower case, the steps taken to investigate the matter, and the initiatives taken and planned to strengthen processes and controls with respect to AML and KYC in the Baltics. The Whistleblower’s actual reports were not shared with the board.

In the spring and early summer of 2014, different work streams were formed to address the whistleblower’s findings. Group Legal proposed hiring an external consultancy to conduct an “[i]n inquiry into allegations of misconduct” on the basis of the whistleblower and to review “critical information on a number of irregularities involving senior members of staff.” This proposal was rejected by two members of the Executive Board. As an alternative, Group Legal asked Group Compliance & AML to “take on the task of bringing this whistleblower matter to an end.” However, Group Legal provided Group Compliance & AML the whistleblower allegations in very broad terms and left out some allegations entirely, including allegations of internal collusion.

After reviewing the whistleblower allegations, Group Compliance & AML sent a list containing “facts and mitigation actions” and a “conclusion” for each allegation. Upon submitting this list to Group Legal, Group Internal Audit, and two members of the Executive Board, Group Compliance & AML indicated “no more action will be done due to the specific allegations” and they would be following “the progress of the suggested actions.” As for the five whistleblower allegations which had been verified to be true, reference was made to the AML Action Plan for the Baltics. Regarding the two whistleblower allegations in the process of being verified, reference was made to Group Legal. Finally, as for seven whistleblower allegations not verified or only partly verified, very little action was identified. After this, there was no additional investigation into the whistleblower allegations.

In early July, Group Internal Audit followed up on its Estonian branch audit from February.

Regarding non-resident customers onboarded since March 1, 2014, Group Internal Audit had “no major comments to the quality of the due diligence requirements applied and completeness of the documentation collected and filed by the area.” However, Group Internal Audit made critical comments on the ongoing customer review based on a sample of eight customers, which had all been reviewed and confirmed by the branch. Around the same time, in response to an inquiry from Group Internal Audit, Business Banking noted that “[t]he allegations made by the whistleblower have all been investigated.”

In May 2014, Business Banking reviewed the preliminary findings of a Baltic Banking strategy review with the Executive Board. The presentation noted that “[t]he current performance will be difficult to maintain and there are a number of challenges going forward,” including “limited future appetite for non-resident business.” In the presentation, AML requirements were overall seen as a threat. A separate slide titled “Significant change in appetite for non-resident business will reduce net profit for the Baltic operation” provided information on the Non-Resident Portfolio, noting that it contributed “90% of the profit before tax for Estonia.” The presentation also recommended a strategy which involved “a reposition towards a Corporate Baltic bank with focus on Nordic customers,” including “[g]radually run-off of Non-resident business.” A revised version of the presentation was delivered to the Board of Directors on June 26, where it was noted that there was “limited future appetite for non-resident business,” and repositioning remained the recommended strategy. According to the meeting minutes, the:

[CEO] emphasized that the Baltic countries are important for many of the Bank’s Nordic corporate clients and particularly the Finnish customers. Further, [CEO] found it unwise to speed up an exit strategy as this might significantly impact any sales price. Lastly, [CEO] and [name] explained the development of the Baltic countries. The preferred option would be to support Nordic corporate clients, but a closer review of the business case needed to be undertaken, concluded [CEO].

The Board Chairman concluded the meeting by noting that “the Board was supportive of the proposed repositioning towards a corporate bank,” but that “all exit options in respect of the non-resident and retail business, including a potential three-way merger, should be further explored prior to making a decision.”

At their meeting on October 28, the Board of Directors debated the repositioning strategy for the Estonian branch as well as a possible sale of the Non-Resident Portfolio. According to the meeting minutes, the Board resolved that “management should continue to consider all strategy options, including a sale, and revert to the Board with a recommendation at the Board meeting in January 2015 at the latest.”

In September, the EFSA delivered their summary findings from a branch AML exam conducted in June and July. Their summary, which was shared with several Executive Board members, found that “Danske Bank systematically established business relationships with persons in whose activities it is possible to see the simplest and most common suspicious circumstances.” A number of details were given, which led to the observation that “[w]e have therefore systematically identified situations during our on-site inspection where Danske Bank’s system for monitoring transactions and persons is effectively not working.” In the draft report, the EFSA voiced its suspicion that at the branch, “economic interests prevail over the obligation to apply enhanced due diligence measures.”

Group Legal shared the English summary of the draft inspection report with Group Compliance & AML. While the Executive Board was never supplied a copy of the EFSA’s draft inspection report, its findings were discussed at an Executive Board meeting on October 7. From the meeting minutes:

The Bank has recently received a drafted report from the Estonian FSA where they point out significant challenges regarding non-resident customers. According to [name] there was no cause for panic as the findings have been addressed in the ongoing process improvement. [Name] will travel to Estonia and assist the Estonian organisation.

At their October meeting, the Audit Committee was informed that the EFSA’s draft inspection report included “rather harsh language from the Estonian FSA” and that “[a]ll observations have been thoroughly reviewed by the local compliance and legal teams in Estonia as well as by Group Legal together with external Estonian legal counsel.”

In December, the EFSA released their final inspection report, which included more specific findings but otherwise echoed the draft report’s finding of significant weaknesses in the branch’s AML procedures. Group legal provided the DFSA with information from the report, but not the actual report.

Neither the Audit Committee nor the full Board of Directors received a copy of the EFSA’s draft, or final, inspection report.

In December, Baltic Banking approved a new policy for the Non-Resident Portfolio. The policy emphasized that “[w]hen establishing customer relationship and opening an account the bank must make sure that the customer has legitimate business reasons to operate in Baltic countries or neighboring region.” In relation to customer onboarding and understanding the business model of the customer, the source of funds would also have to be identified. As for existing customers, it was now stated that “[s]trategically the bank foresees winding down relationships by end of second quarter 2015.”

Questions for Directors

- How would you assess the Board of Director’s performance in addressing the whistleblower’s allegations?

- In the debates summarized above, are the members of the Executive Board and Board of Directors properly weighing the relevant factors in determining whether, and how, to do business in Estonia? What are those factors?

- Is the failure to provide the Board of Directors with the critical report of the Estonian financial regulator acceptable? Should directors insist on reviewing all official supervisory communications?

2015

In January, the Executive Board recommended to the Board of Directors that the Estonian branch exit the non-resident segment and focus “only on customers with a real Baltic presence.” The Board of Directors approved this recommendation and in Danske Bank’s annual report for 2014, goodwill for the Estonian branch was written down to zero due to “a worsening of the long-term economic outlook in Estonia and the planned repositioning of the personal banking business in 2015.”[32]

The DFSA and EFSA ramped up their scrutiny of Danske Bank’s AML practices in 2015. The DFSA conducted an exam in February, during which the EFSA’s inspection report from the previous December was shared, as was the report from the external consultancy from April 2014. The DFSA released their draft inspection report in June, where it was noted that the Estonian branch’s “risk-mitigating measures . . . have been totally insufficient and in violation of the local AML-rules.”

In September, the DFSA followed up on their draft inspection report from June, noting that they found “cause to reprimand the bank’s board of directors for not having identified the Estonian branch’s risk in the AML area, including not having determined the nature and size of the risks that the branch may assume, and for not having taken sufficiently risk-mitigating measures in this relation in accordance with local legislation.” This reprimand was maintained in the final inspection report issued by the DFSA on March 15, 2016.

Group Internal Audit also followed up on issues identified in 2014, releasing their audit report on June 19, 2015. The report assigned an “Action needed” (the worst possible rating) to the Estonian branch, noting that the “On-boarding process for new non-resident customers’ needs strengthening.” Another observation, “Periodical reassessment for high-risk non-residents needs to be improved” (priority 1), was based on a review of memos from the customer review (“clean-up process of high-risk non-resident customers”). It was also noted that “[i]dentification of ultimate beneficial owners (and ‘controlling interests’) remains in some cases unclear.”

The CEO received the audit report and its findings were included in a long-form audit report submitted to the Executive Board, the Audit Committee, and the Board of Directors for meetings in July.

On May 6, 2015, Danske Bank was contacted at Group level by a correspondent bank that cleared USD transactions for the Estonian branch. The correspondent bank requested that “all payments on behalf [sic] any Shell Company does not get routed” via the correspondent bank. Then in July, another correspondent bank that cleared most of the Estonian branch’s USD transactions notified Danske Bank that “they had found some payments that they were not comfortable with.” The Board of Directors was never informed about either of these correspondences and the Estonian branch was not informed about these matters until August 2015.

In the middle of 2015, Danske Bank accelerated the run-off of the Non-Resident Portfolio in Estonia. In a September letter to the EFSA, the Estonian branch compared the number of customers at the beginning of 2014 (3,743) with the number of customers at the end of July 2015 (2,169). They noted that “[d]uring the year 2015, the Branch has issued to 2,261 such customers notices of terminating the business relationship with them” and that “[p]roviding that the business relationships are terminated by the deadlines specified in the notices, the serving of high-risk customers will be diminished to a significant extent by the end of 2015.”

On December 23rd, the International and Private Banking Division within the Estonian branch was closed and most of the customer relationships were ended. As was reported to the Board of Directors in May 2016, “[t]he non-resident customer business was fully closed at the end of 2015, addressing a significant compliance and reputational risk for the Group.”

Questions for Directors

- What should the Board of Directors’ response be to the criticism of its performance by the Danish financial regulator?

- What role should the Audit Committee play in investigating internal audit findings and ensuring they are adequately addressed by the Bank?

2016 – 2017

Despite having effectively closed the Non-Resident Portfolio in Estonia, Danske Bank continued to incur reputational and legal damages associated with past activity in the Estonia branch. In 2016, news reports out of Azerbaijan implicated the Estonian branch in a political payoff scheme involving an Italian politician and Azerbaijani government officials. These reports prompted the creation of an informal task force within Danske Bank—involving Group Compliance & AML, Group Legal and Group Communications & Relations—that provided periodic updates to the CEO.

In March 2017, an anti-corruption NGO, working with reporters in Denmark, identified Danske Bank as one of the banks being used to launder money as part of the “Russian Laundromat” scheme. The scheme involved moving $20 billion out of Russia from 2010 to 2014 through a network of global banks. Most of the beneficiaries were Russian elites, many with ties to the Kremlin. Shortly before the story was published, Danske’s CEO informed the chairman of the Board, who then notified the whole Board of Directors. According to a Danske Bank internal memo prepared around the same time, the Bank identified 1,567 transactions and a flow of approximately $1.2 billion as part of the scheme.

The Russian Laundromat was discussed at the Executive Board meeting on March 28, 2017. According to Group Legal, “at this point, no final conclusions could be drawn as data and information on the case were still being gathered,” but “the Estonian branch seemed to have been misused for money laundering between 2011 and 2014.”

In March 2017, Danske Bank was asked by the DFSA to provide further information regarding the Estonian branch in relation to the Russian Laundromat. The DFSA’s subsequent investigation led to multiple orders and reprimands that were delivered in May 2018.

The Executive Board and Board of Directors were updated on the Russian Laundromat in April. As part of these updates, Group Compliance & AML wrote that ”[i]n countries where the bank operates on separate IT systems not connected to the central IT platform, this [that is, strong AML controls] becomes a challenge, as development of transaction monitoring scenarios needs to be done locally.”

Recognizing the severity of the situation, Danske Bank hired the regulatory consultancy Promontory, who was tasked with conducting a root-cause analysis. Promontory presented their results—including their finding that $30 billion in non-resident money passed through the Estonian branch in 2013 alone—to the CEO and Executive Board in June 2017. The Board of Directors was presented with a shorter version of their report in August.

In a press release on September 21, 2017, Danske Bank informed the public of Promontory’s findings, concluding that “several major deficiencies led to the branch not being sufficiently effective in preventing it from potentially being used for money laundering in the period from 2007 to 2015.” The three major deficiencies identified were:

- The lack of a proper culture for and focus on anti-money laundering at the Estonian branch

- Inadequate governance in relation to compliance and risk

- Management follow-up and control were highly dependent on local country management

In the same press release, Danske Bank announced they were launching an expanded investigation into money laundering at the Estonian branch, to be conducted by the newly established Compliance Incident Team, which would take 9 to 12 months to complete.

While the Bank was waiting for the expanded investigation to reveal the full extent of money laundering in the Estonian Branch, they were staring down multiple legal and regulatory investigations. Danske Bank’s future, and the futures of its top executives, were very much in doubt.

Questions for Directors

- How would you assess the Board’s performance in attempting to understand the scale of the problem in the Estonian branch? Should they have hired an external consultancy sooner?

- What other actions could, or should, the Board of Directors take to redeem the Bank’s reputation and regulatory standing?

Postscript

In September 2018, Danske Bank published a report of its own independent legal inquiry (the Bruun & Hjejle report). The report concluded that non-resident customers had completed transactions totaling roughly EUR 200 billion through the Estonian branch in the period 2007-2015, and that a large proportion were suspicious and potentially illegal money laundering activities.

The investigation also found 42 employees and agents were involved in suspicious activity, and they were subsequently reported to the Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit in accordance with Estonian law. In addition, eight former employees were reported to the Estonian police by Danske Bank for suspected criminal acts. In December 2018, ten former employees of the branch were arrested in Estonia.

In October 2018, Thomas Borgen was fired as CEO. Several weeks later, the DFSA blocked the Board of Director’s unanimous choice of Jacob Aarup-Andersen to be Danske Bank’s next CEO. Although he was head of the wealth management unit and the former CFO, the DFSA believed that Aarup-Andersen lacked sufficient experience “within Danske Bank’s business areas.”

In November 2018, Ole Andersen was ousted as Danske’s chairman by the bank’s main shareholder, the Maersk family.

In May 2019, the Board of Directors appointed Chris Vogelzang, the former head of ABN Amro’s retail and private banking operations, as Danske Bank’s new CEO.

The bank continues to be subject to multiple legal inquiries, including a criminal investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.

APPENDIX

EXHIBIT A

LIST OF SIGNIFICANT MERGERS and ACQUISITIONS SINCE 1990[33]

- 1990: Merger of Den Danske Bank, Handlesbanken and Provinsbanken, competing Danish banks.

- 1997: Opening of branches in Oslo, Stockholm and Helsinki and acquisition of Ostgota Enskilda Bank in Sweden.

- 1999: Acquisition of Fokus Bank in Norway and opening of representative office in Warsaw, Poland.

- 2000: Acquisition of controlling interest in St. Stanislaus Polish-Canadian Bank. S.A., later renamed Danske Bank Polska S.A.

- 2001: Merger with RealDanmark [BG Bank and Realkredit Danmark].

- 2004: Acquisition of Northern Bank in Northern Ireland and National Irish Bank in the Republic of Ireland.

- 2006: Acquisition of Sampo Bank of Finland, with operations in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Russia.

EXHIBIT B

DANSKE BANK RISK MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

Danske Bank’s Corporate Hierarchy in 2007[34]

Risk Organization of the Danske Bank Group[35]

[1] Unless otherwise footnoted, all quotations within the case study come from the Bruun & Hjele Report. See Bruun & Hjele, Report on the Non-Resident Portfolio at Danske Bank’s Estonian branch (2018), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2018/9/report-on-the-non-resident-portfolio-at-danske-banks-estonian-branch-.-la=en.pdf [hereinafter Bruun & Hjele Report]

[2] Danske Bank, Corporate Story, at 9 (Feb. 2018), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2018/2/corporate-story-2017.pdf.

[3] All totals are converted into USD from Danish Krone as listed in Danske Bank 2017 Annual Report. The exchange rate as of 12/31/2017 was used. See Danske Bank, 2017 Annual Report, at 6 (Feb. 2018), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2018/2/annual-report-2017.pdf [hereinafter Annual Report].

[4] GDP total provided by the World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=DK

[5] See Exhibit A in the Appendix for a list of significant mergers and acquisitions since 1990.

[6] Annual Report, supra note 3, at 69. On 12/31/2017, 1 USD = 6.1996 DKK.

[7] For more information on Danske Bank’s corporate governance and risk management, see Exhibit B in the Appendix.

[8] Danske Bank, Risk Management 2007, at 11 (Feb. 2008), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2008/1/risk-management-2007.pdf.

[9] Danske Bank, Risk Management 2012, at 9 (Feb. 2013), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2013/2/risk-management-2012.pdf.

[10] Annual Report, supra note 3, at 8.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 11.

[13] Press Release, Danske Bank, Danske Bank Group acquires Sampo Bank, (Nov. 9, 2006), https://danskebank.com/en-uk/press/News/Pages/pr20061109.aspx [hereinafter Press Release].

[14] Bruun & Hjele Report, supra note 1, at 39.

[15] Danske Bank, 2007 Annual Report, at 17 (Feb. 2008), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2008/1/annual-report-2007.pdf.

[16] Bruun & Hjele Report, supra note 1, at 39-40.

[17] Sampo Group, Sampo Annual Report 2003, at 14 (Feb. 2004), https://sampo-annualreports.studio.crasman.fi/file/dl/i/GnwXOw/YY5xT5A6lvT-gaGBUeXYFg/Sampo_AnnualReport_2003.pdf.

[18] Sampo Group, Sampo Annual Report 2006, at 10 (Feb. 2007), https://sampo-annualreports.studio.crasman.fi/file/dl/i/lTqAdQ/zhUQKCE24AjWvK6teTHTww/Sampo_AnnualReport_2006.pdf.

[19] Bruun & Hjele Report, supra note 1, at 40.

[20] Sampo Group, Sampo Annual Report 2005 and Sampo Annual Report 2006, at 116 and 135 respectively.

[21] Press Release, supra note 14.

[22] Id.

[23] Danske Bank, Stepping Up Retail Banking Expansion: Acquisition of Sampo Bank, at 6 (Nov. 9, 2006), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2006/11/acquisition-of-sampo-bank.pdf.

[24] Id. at 8.

[25] Id. at 10.

[26] Press Release, supra note 14.

[27] Danske Bank, 2007 Annual Report, at 16 (Feb. 2008).

[28] Eesti Pank, Statistical indicators, http://statistika.eestipank.ee/#/en/p/900/r/936/806.

[29] Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) is an independent structural unit of the Estonian Police and Border Guard Board. The Financial Intelligence Unit analyses and verifies information about suspicions of money laundering or terrorist financing, takes measures for preservation of property where necessary and immediately forwards materials to the competent authorities upon detection of elements of a criminal offence.

[30] The DFSA did prepare an annex in their 2019 report on the Danish FSA’s supervision of Danske Bank dedicated to AML supervision in the Estonian branch but this annex was not publicly released. See Danish Financial Supervisory Authority, Report on the Danish FSA’s supervision of Danske Bank as regards the Estonia case, (Jan. 28, 2019), https://www.dfsa.dk/~/media/Nyhedscenter/2019/Report_on_the_Danish_FSAs_supervision_of_Danske-Bank_as_regards_the_Estonia_case-pdf.pdf?la=en.

[31] Press Release, Danske Bank, Management changes – New Chief Executive Officer (Sept. 16, 2013), https://danskebank.com/en-uk/press/News/Press-releases-and-company-announcements/Company%20announcement/Group/Pages/ca16092013.aspx.

[32] Danske Bank, 2014 Annual Report, at 88 (Feb. 2015), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2015/2/annual-report-2014.pdf.

[33] Danske Bank, Our history, https://danskebank.com/about-us/our-history.

[34] Danske Bank, Corporate Governance Fact Sheet (Apr. 2007), https://www.danskebank.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/CGFactSheetEN.pdf.

[35] Danske Bank, Risk Management 2007, at 9 (Feb. 2008), https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2008/1/risk-management-2007.pdf.