Bobot: An autonomous pet engagement robot

A robotic system that brings intelligent, natural, and adaptive play to pets —— anytime, in any environment.

Course:

ME555 – Experimental Design & Research Methods

Duke University, Fall 2025

Concept image:

Biomimetic intelligence for real-world pet enrichment.

Abstract

Bobot is designed to address the challenge of environmental enrichment for companion animals. By integrating biomimetic intelligence, the system produces natural, adaptive, and safe interactions in unstructured indoor environments. Unlike pre-programmed mechanical toys, Bobot utilizes real-time perception and machine learning algorithms to model prey-like escape and engagement behaviors, thereby enhancing an animal’s cognitive stimulation and physical activity. The system demonstrates that biologically grounded motion strategies, combined with modern robotic perception and control, can significantly improve the quality of pet–robot interaction.

Introduction

Animals rely on instinct-driven play behaviors for physical exercise, cognitive development, and emotional well-being. However, in modern households, companion animals often endure sedentary lifestyles with limited environmental stimulation. This deficit frequently manifests as anxiety-related disorders [1], obesity [2], and destructive behaviors [3]. While the global pet care market is projected to reach approximately $4.3 billion by 2032 [4], signaling a critical demand for high-quality interaction, current commercial solutions remain functionally limited.

Existing devices generally lack the intelligence required to perceive indoor complexity or adapt to animal behavior. Specifically, laser-based toys, though prevalent, pose potential ocular safety risks and the lack of physical capture can lead to frustration [5]. Conventional teaser wands depend on continuous human intervention; yet, modern work schedules often preclude constant companionship [6].

These limitations motivate the development of autonomous systems capable of bridging the gap between human unavailability and pet needs. Prior research suggests that a robot offers the distinct advantage of physical manipulation of objects in the enclosure [7], and that introducing diverse interactive modes can significantly enhance the level of participation [8]. Building upon these insights, we propose Bobot, an autonomous robotic system designed to provide interactive, adaptive, and biologically meaningful play. Grounded in ethology, robotics, and machine learning, Bobot aims to generate dynamic, prey-like behaviors that maintain engagement while ensuring safety. By modeling natural motion patterns—such as rhythmic oscillations, sudden escape maneuvers, and vertical jumps—the system enables a richer form of interaction that aligns with the evolutionary instincts of predator species. Bobot represents a significant step toward redefining the human-pet-robot relationship through intelligent enrichment.

System Architecture

The Bobot system is designed as a modular, integrated mechatronic platform capable of autonomous interaction in unstructured environments. Physically, the system comprises five subsystems: Perception, Control, Mobility, Power, and End-effectors. To achieve adaptive and naturalistic interaction, the functional architecture is organized into three core processing modules: the Perception Module, the Biomimetic Motion Generation Engine, and the Kinematic Control Module.

A. Perception Module The system utilizes an RGB-D depth camera as the primary sensory input. Integrated with machine learning-based detection models, this module performs real-time pose estimation and behavioral classification. It identifies specific animal postures (e.g., sitting, lying down, standing, jumping) and tracks dynamic movements, converting visual data into state vectors that represent the animal’s current engagement level.

B. Biomimetic Motion Generation Engine Behavioral data is fed into the Biomimetic Motion Generation Engine. Drawing upon ethological studies of avian and insect flight patterns, this engine synthesizes stochastic, prey-like trajectories within the constraints of the indoor space. Unlike repetitive mechanical loops, the engine generates non-deterministic paths that mimic natural evasion strategies, ensuring high cognitive stimulation.

C. Kinematic Control Module To translate these generated trajectories into physical motion, the Kinematic Control Module employs a Damped Least Squares (DLS) inverse kinematics solver. This algorithm ensures smooth joint interpolation and singularity avoidance, guaranteeing safe and stable execution of rapid movements.

The integration of real-time perception and biomimetic control creates a closed-loop system. Bobot dynamically adjusts its motion strategy based on the animal’s inferred “hunting intent” and behavioral changes, fostering a responsive and continuously evolving play experience.

- Perception & Mapping – Recognize cat pose and indoor space using RGB-D sensing and obstacle-aware path planning.

- Biomimetic Path Generation – Generate prey-like, biologically inspired motions with built-in randomness and safety constraints.

- Robust Control & Safety – Implement grasping and compliant control to allow safe, tangible interactions with pets.

- Simulation & Validation – Train and test algorithms in simulation before conducting real-world experiments in varied layouts.

- Learn how to integrate RGB-D sensing, mapping, and obstacle avoidance in real-world robotics.

- Gain proficiency in ROS2, MuJoCo(simulation platforms), and planning frameworks.

- Understand and implement robot arm kinematics, grasping, and compliant control.

- Apply machine learning methods to generate biomimetic trajectories for robots.

- How to design biologically inspired play strategies (fluttering, retreating, unpredictable prey-like motions) within confined spaces?

- How to establish an adaptive feedback loop that correlates robotic stimuli with real-time behavioral metrics (e.g., attention, engagement) to dynamically modulate play difficulty, thereby mitigating habituation and sustaining long-term cognitive interest?

- How to implement a real-time vision system capable of distinguishing fine-grained animal behaviors (e.g., stalking, pouncing, or disinterest) amidst dynamic occlusions and varying lighting conditions?

- What is the market feasibility of translating research-grade robotic arms into low-cost, consumer-ready products?

Methodology

A. Hardware Design

The hardware development of Bobot followed an iterative engineering process prioritizing simplicity, safety, and material efficiency. In the preliminary phase, three candidate robotic configurations were evaluated using a weighted decision matrix (Total: 25 points), assessing Simplicity (10), Safety (10), and Cost-Efficiency (5). The final selection—a fixed-base kinematic configuration—demonstrated the optimal balance of these criteria. This design ensures a stable center of mass, significantly mitigating tipping risks in cluttered indoor environments. Furthermore, by integrating a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) manipulator (Nova), the system eliminates the need for a mobile chassis, maintaining structural robustness while optimizing development costs.

Three different initial design ideas and scoring rankings

1. Fixed-Base Manipulator (Selected Design) Evaluation: : 9+9+5=23

High Safety | Low Complexity | Moderate Cost

This configuration anchors the robotic arm to a stable platform. It was selected for its superior stability, which eliminates tipping risks, and its simplified control logic. By utilizing the existing Nova arm without an additional mobile chassis, it achieves the optimal balance between mechanical robustness and cost-efficiency.

2. Mobile Manipulator System Evaluation: : 6+7+4=17

High Scalability | High Complexity | Safety Risks

This design mounts the arm on a wheeled chassis to expand workspace coverage. While scalable, integrating autonomous navigation significantly increases software complexity. Furthermore, moving parts introduce collision risks with pets, making it less suitable for early version.

3. Overhead Track System Evaluation: : 5+7+3=15

Low Footprint | Highest Cost | Installation Difficulty

This system mounts the manipulator on a ceiling rail. Although it saves floor space, it presents the highest installation complexity and cost. The potential risk of components detaching and falling onto the pet below poses a critical safety hazard, rendering it impractical for our first version.

To address the unpredictability of dynamic physical interactions—where companion animals may strike or bite the effector—a compliant mechanism was engineered for the end-effector. We analyzed two implementation strategies: a custom 3D-printed gripper and a spring-loaded commercial teaser. In both designs, mechanical compliance functions as a passive impact-attenuation interface. This decoupling protects the robot’s actuators from sudden impulse forces and ensures the safety of the animal, effectively extending the hardware’s operational lifespan.

B. Perception Model

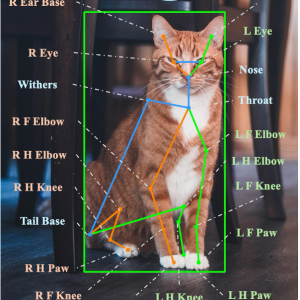

The perception pipeline of Bobot comprises three hierarchical stages: Cat Detection, Keypoint Extraction, and Action Recognition.

Detection: The initial stage employs the SAM3 model to perform robust, segmentation-driven localization. This approach ensures consistent detection performance under challenging indoor conditions, including varying illumination and dynamic occlusions[9][10].

Keypoint Extraction: Following detection, an HRNet model, trained on the Animal Pose dataset, extracts a consistent set of 20 skeletal landmarks. These keypoints provide a low-dimensional yet expressive encoding of the animal’s posture[11][12].

Action Recognition: To facilitate behavioral understanding in domestic settings, we constructed a task-specific dataset of approximately 800 manually curated images, expanding upon existing public repositories. Leveraging these samples, we implemented a lightweight clustering-guided classification method based on k-means feature grouping. This system categorizes behaviors into four fundamental states—Sit, Stand, Lie, and Jump—which serve as discrete inputs for interaction planning. The integration of pre-trained large models with our fine-tuned dataset enables precise behavior interpretation.

C. Imitation Learning

The control strategy is formulated as a decision-making problem under partial observability, modeled via a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP). Since the robot cannot directly observe the full environmental state, it relies on partial sensory inputs. To optimize policy execution under these conditions, we employ Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), a policy-gradient reinforcement learning algorithm selected for its stability in continuous control tasks[13][14].

D. Biomimetic Motion Design

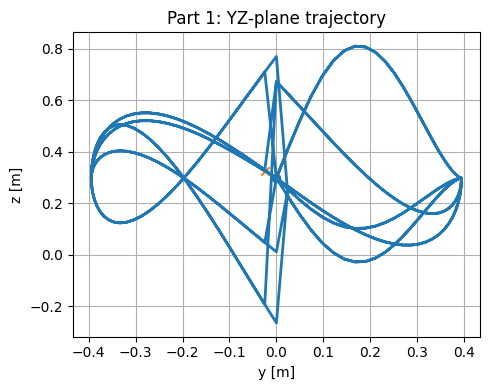

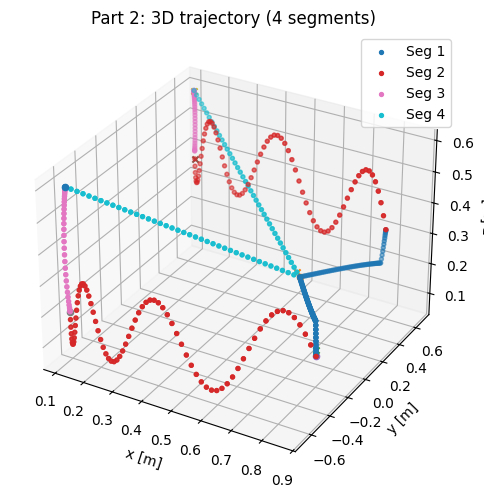

Prior to RL deployment, we utilize Imitation Learning within a simulation environment to synthesize biomimetic reference trajectories. These paths mimic the stochastic motion patterns of avian and insect flight[15-18].

- Attention Phase: Upon detection, Bobot initiates a trajectory generated by sampling from parametric waveforms (sine, triangle, and sawtooth), blended with randomized perturbations. This mimics the rhythmic yet unpredictable micro-motions characteristic of biological prey.

- Engagement Phase: As the subject approaches, the system transitions to a structured, goal-directed chase sequence composed of four distinct behavioral segments:

Approach: Subtle movement toward the subject to provoke curiosity.

Fast Escape: Rapid, prey-like retreat to trigger predatory instinct.

Upward Movement: Vertical elevation of the effector to induce jumping.

Return & Reset: Repositioning to initialize the next interaction cycle.

This structured “chase-and-escape” pattern, grounded in biological motion, ensures a dynamic interaction that feels natural and evolutionarily stimulating for the animal.

E. Simulation

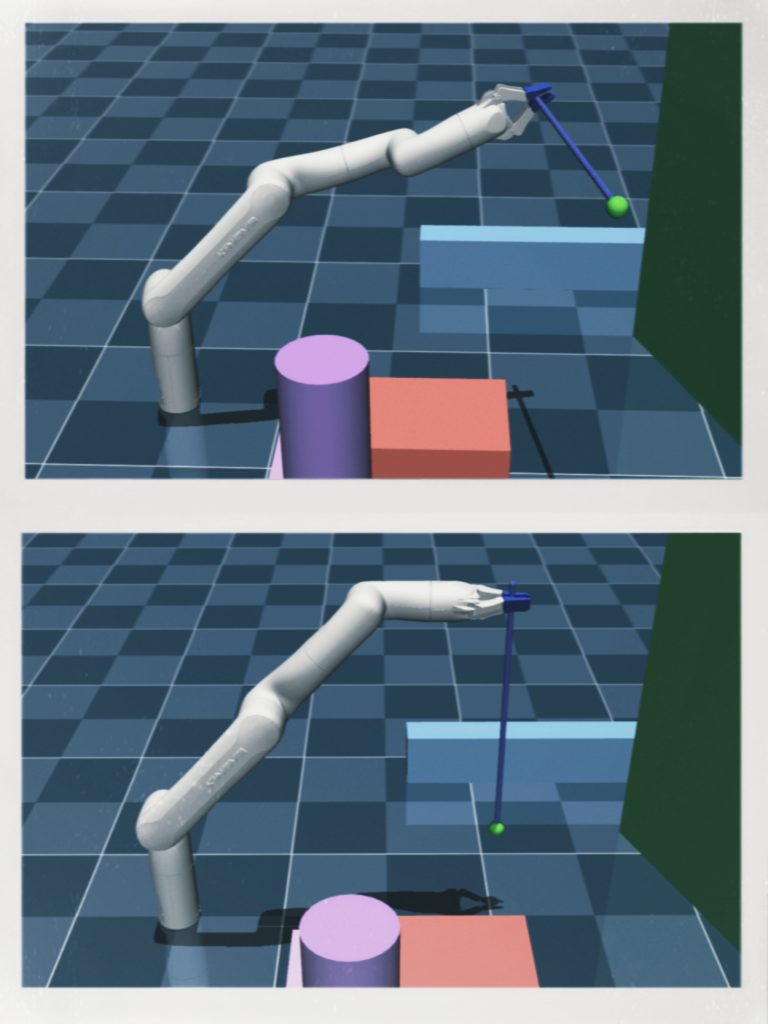

The system simulation is implemented in MuJoCo. This engine was selected for its fast computation speed and accurate contact physics, which are essential for testing dynamic interactions. By utilizing the built-in Kinova Gen3 Lite model, we can directly validate control and imitation learning algorithms, effectively bypassing the need to reconstruct mechanical models from scratch.

Environmental Object Settings:

- Robotic arm:

Imported from the existing model, including the gripper part - Obstacles:

Currently, cylinders, cuboids, and cubes have been randomly imported, and collision volumes have been set to ensure that the robotic arm or cat toy cannot pass through the obstacles. - Cat toy:

The end of the cat toy is replaced by a small ball and has been installed at the center of the mechanical arm’s gripper - Cat:

An automatic chasing motion agent mode is adopted, which will automatically chase the small ball at the end of the cat teaser

Holding Method

Ways to hold a cat teaser:

1. Tilt at a certain angle

Good for lateral swipes and sweeping motions; Safer contact angles for paw-swipes.

2. Vertically downward

Easier control and planning; Safer distance management relative to floor/furniture.

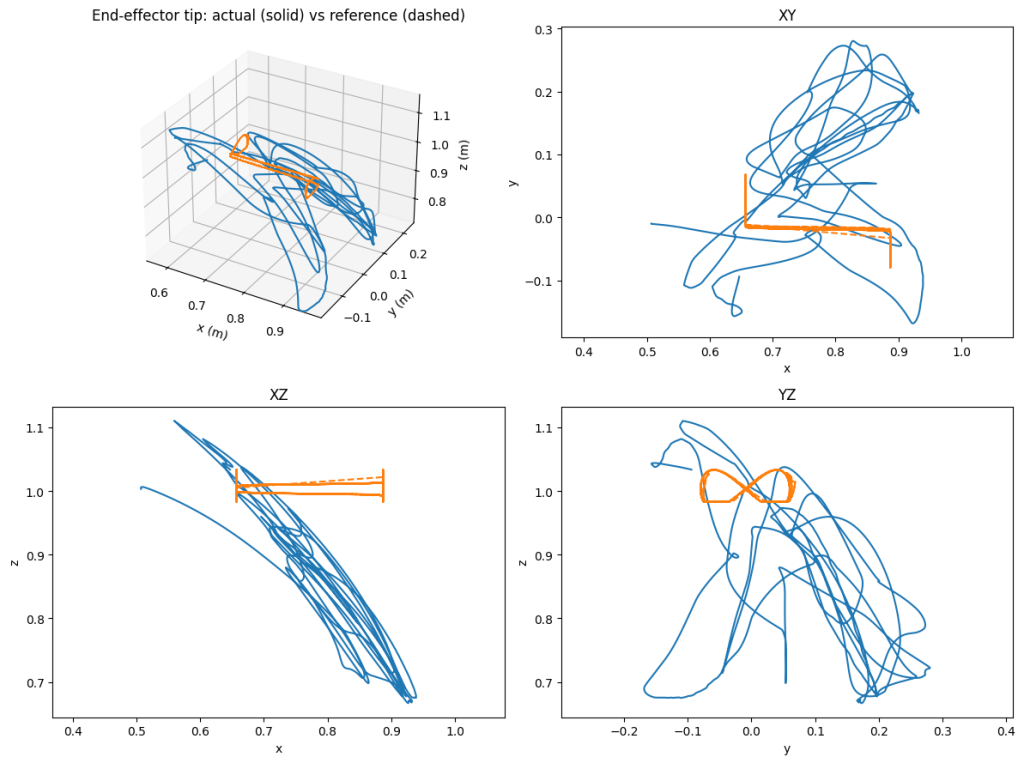

Inverse Kinematics

Damped least squares (DLS) is a stabilized IK solution method that adds a regularization term to the standard Jacobian inverse. It can achieve smooth and safe end-to-end convergence in singular or noisy environments and is one of the most commonly used numerical IK algorithms in modern robot control, especially in real-time simulation.

The initial error was large and the reproducibility was poor.

In the new version, two parameters were modified:

1.Step size gain: Controls the proportion of each joint update

2. Upper limit of single-step joint Angle variation:Increasing the step size gain while reducing the single-step joint Angle change, when combined, = “faster willingness + smaller single-step limit” : it can not only rapidly reduce the propulsion error but also avoid taking too large a step and causing oscillation, so the body sensation will be significantly better.

The new version has a small vibration amplitude and performs well!

Future Work

Real world test:

Use the Nova robotic arm and a RGB-D camera;

Put different barriers around;

Check if it can finish the obstacle avoidance & mimicry path planning.

An important future extension is the integration of a ball or toy throwing module to support richer forms of interaction, particularly for pets that are highly responsive to chasing and retrieval behaviors. Combined with the existing perception and action recognition pipeline, the system can adaptively determine the timing, direction, and strength of each throw based on the pet’s current posture and behavior. Compared to purely visual stimuli such as laser pointers, physical toy throwing provides tangible rewards and realistic feedback, which can significantly enhance engagement and exercise intensity. Future work will focus on designing low-cost, modular, and safety-aware throwing mechanisms suitable for everyday home environments.

As future work, we plan to extend the current fixed-base robotic arm into a mobile interaction system by integrating a low-speed, safety-oriented mobile base. With indoor SLAM and obstacle-aware navigation, the robot will be able to reposition itself autonomously within confined spaces, effectively enlarging the interaction workspace. This mobility allows the system to adapt to the pet’s changing location instead of being constrained to a single fixed point, enabling more diverse and engaging play patterns. The mobility module will be designed with an emphasis on low velocity, high stability, and pet safety, ensuring reliable deployment in real home environments.

References

[1]“The Dangers of Not Getting Your Pet Enough Exercise,” Loving Care Pet Hospital, Dec. 21 2023. Available: https://lovingcarepethospital.net/the-dangers-of-not-getting-your-pet-enough-exercise/.

[2] Á. Pogány, O. Torda and L. Marinelli, “The behaviour of overweight dogs shows similarity with personality traits of overweight humans,” *R. Soc. Open Sci.*, vol. 5, no. 6, art. no. 172398, Jun. 2018

[3] K. Hahn, “How Indoor Cats Lack Enrichment and How You Can Help!,” Cheyenne Animal Shelter, Oct. 17 2024.

[4] D. Patel, “Interactive Cat Toys Market Report | Global Forecast From 2025 To 2033,” Dataintelo, Published [Online]. Available: https://dataintelo.com/report/interactive-cat-toys-market.

[5] D. F. Sieck, “Enhancing Feline Exercise: A Safe YOLO-Based Laser Toy,” Master’s thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC), Barcelona, Spain, Jul. 18, 2023.

[6] L. Gillet, B. Simon, and E. Kubinyi, “The role of dogs is associated with owner management practices and characteristics, but not with perceived canine behaviour problems,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14

[7] E. Schneiders, S. Benford, A. Chamberlain, C. Mancini, S. Castle-Green, V. Ngo, J. Row Farr, M. Adams, N. Tandavanitj, and J. Fischer, “Designing Multispecies Worlds for Robots, Cats, and Humans,” in Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’24), Honolulu, HI, USA, 2024, Art. no. 593, pp. 1–16. doi: 10.1145/3613904.3642115.

[8] M. Delgado and J. Hecht, “A review of the development and functions of cat play, with future research considerations,” Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., vol. 214, pp. 1–17, 2019.

[9] T.-Y. Lin, M. Maire, S. Belongie, L. Bourdev, R. Girshick, J. Hays, et al., “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context,” in Computer Vision – ECCV 2014, D. Fleet, T. Pajdla, B. Schiele, and T. Tuytelaars, Eds., Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 8693. Cham: Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_48.

[10] C. Lyu, W. Zhang, H. Huang, Y. Zhou, Y. Wang, Y. Liu, S. Zhang, and K. Chen, “RTMDet: An Empirical Study of Designing Real-Time Object Detectors,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.07784, 2022.

[11] Cao, H. Tang, H.-S. Fang, X. Shen, C. Lu, and Y.-W. Tai, “Cross-Domain Adaptation for Animal Pose Estimation,” in Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019, pp. 9498–9507.

[12] T. Jiang, P. Lu, L. Zhang, N. Ma, R. Han, C. Lyu, Y. Li, and K. Chen, “RTMPose: Real-Time Multi-Person Pose Estimation based on MMPose,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.07399

[13] Platt, R., Tedrake, R., Kaelbling, L. P., and Lozano-Pérez, T., “Belief space planning assuming maximum likelihood observations,” in Proc. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), Zaragoza, Spain, Jun. 2010, doi: 10.15607/RSS.2010.VI.037.

[14] Tan, J., Zhang, T., Coumans, E., Iscen, A., Bai, Y., Hafner, D., Bohez, S., and Vanhoucke, V., “Sim-to-Real: Learning Agile Locomotion for Quadruped Robots,” in Proc. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, Jun. 2018. [Online]. Available: arXiv:1804.10332.

[15] B. W. Tobalske, “Hovering and intermittent flight in birds,” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 045004, 2010.

[16] B. W. Tobalske, W. L. Peacock, and K. P. Dial, “Kinematics of flap-bounding flight in the zebra finch over a wide range of speeds,” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 202, no. 13, pp. 1725–1739, 1999.

[17] F. T. Muijres, M. J. Elzinga, N. A. Iwasaki, and M. H. Dickinson, “Body saccades of Drosophila consist of stereotyped banked turns,” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 218, no. 6, pp. 864–875, 2015.

[18] P. Domenici, J. M. Blagburn, and J. P. Bacon, “Animal escapology I: theoretical issues and emerging trends in escape trajectories,” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 214, no. 15, pp. 2463–2473, 2011; and “Animal escapology II: escape trajectory case studies,” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 214, no. 15, pp. 2474–2494, 2011.