Motivation

- Stroke recovery needs precision: Patients often have impaired dexterity, grip strength, and ROM.

Clinical scales are limited: Tools like FMA-Hand or ARAT are subjective and not sensitive enough.

Wearable sensors enable accuracy: Flex sensors, IMUs, and FSRs can provide objective, high-resolution data.

Why accuracy matters: Ensures proper training dosage, tracks progress, personalizes therapy, and supports neuroplasticity.

Introduction

In the United States, a stroke occurs every 40 seconds (CDC, 2025). Each year, more than 795,000 people have a stroke. Having a stroke is one of the leading causes of long-term disability worldwide, and hand dysfunction remains one of the most persistent and disabling aftermaths after suffering a stroke. Patients often experience impaired dexterity, reduced grip strength, and limited range of motion (ROM), which restrict their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL).

Effective rehabilitation relies on repetitive, task-oriented training to stimulate neuroplasticity and promote functional recovery. For stroke patients who have decreased motion in their hands, a sequence of exercises involving grasping, pinching, extension, and squeezing to regain flexibility and strength during physical therapy sessions. Rehabilitation is measured by assessments to test range of motion and track changes in flexion, extension, and force of each digit. For example, the Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (Gladstone, et al., 2002) assesses motor function, balance, joint range of motion and joint pain, and the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) to measure upper limb function (Lyle, 1981). However, most progress can be measured by improvements in flexion and extension in the affected extremity for stroke patients who have lost mobility in their hands.

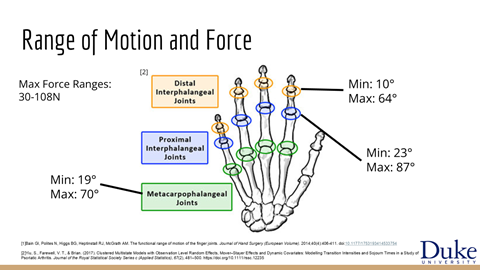

A functional range of motion is established for each joint of the fingers, with 10°-64° for distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, 23°-87° for proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and 19°-70° Metacarpophalangeal (MPP) joints. It should be noted that functional range of motion is distinct from active range of motion, where the active range of motion is the joint degree to which the muscle can move and the functional range of motion is the degree of flexion needed to perform everyday tasks.

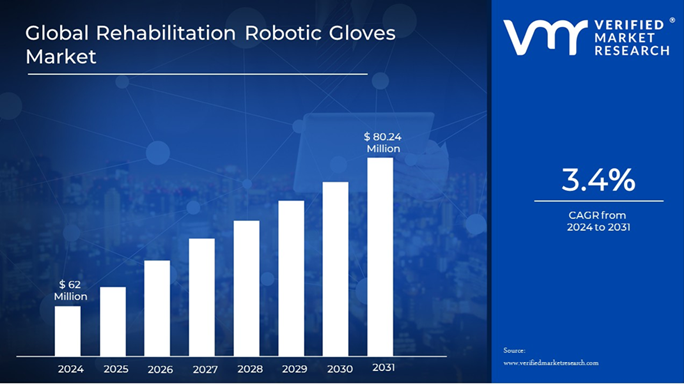

The American Association of Physical Therapists reported a 5.2% shortage of physical therapists in 2022, with a projection of demand growing faster than the rising population (Zarek, et al., 2025). Shortages risk patients not being able to receive care in appropriate time, which is crucial to recovery and regaining mobility, especially to older patients. To help alleviate the demand of physical therapists, researchers have shifted a focus towards robotic rehabilitation devices and the market is expected to reach $80.2 million in 2030.

Previous studies have demonstrated that robotic hand exoskeletons can improve motor outcomes and even enhance cortical excitability (Singh et al., 2021), that force-feedback robotic gloves combined with task-oriented training can significantly improve FMA-Hand, ARAT, grip strength, and ROM (Li et al., 2024), and that even passive robot-assisted range of motion training is feasible and beneficial in chronic stroke patients (Hsu et al., 2022). A recent meta-analysis further confirmed that passive movement has significant effects on motor function and disability (Abdullahi et al., 2025).

Despite these advances, existing robotic devices often lack engagement mechanisms, rely mainly on passive or assisted flexion motivational feedback, and provide limited precision in quantifying movement quality. To address these gaps, we propose a novel design of cost-effective force-assisted rehabilitation glove. This device integrates repetitive passive and active-assisted movements with real-time force and motion sensing. By combining accurate measurement and force feedback, our glove aims to enhance patient motivation, deliver high-dose task-oriented training, and ultimately promote neuroplasticity and functional recovery in stroke survivors in the comfort of their home.

Market value

The Global Robotic Glove Market for Stroke Rehabilitation Market size is expected to be worth around US$ 80.24 Million by 2031, , growing at a CAGR of 3.4% during the forecast period from 2024 to 2034.

Existing Products

Device | Feature |

Motus Hand ($15,000 – $30,000) | Repetitive task training |

IpsiHand ($15,000 – $30,000) | BCI-driven exoskeleton |

Syrebo Glove ($5,000 – $10,000) | Finger joint exercise |

Soft Robotic Glove ($2,000 – $5,000) | Textile + pneumatic soft glove |

Problem statement

Those who suffer from strokes require months of rehabilitation to regain some of the loss of function in their body, however there are many barriers such as limited healthcare, finances, or transportation.

Many barriers could be resolved, especially for patients struggling with hand mobility, by a robotic exoskeleton glove that performs guided rehabilitation exercises in their own home. A glove with accurate joint measurement sensors and a reviewable report would allow physical therapists to tailor treatment plans for patients and provide a more efficient and accessible rehabilitation.

Project Goals

- Lightweight, safe glove

- Portable power source

- Motorized movement to bend fingers

- Sensors to record motion

- Real-time data generation

MindMap

When creating a medical product there are several considerations that must be taken to ensure the product is safe and easy for users. After setting our main project goals, it was crucial for our group to create a mindmap of all the essential components we needed for our project and consider what we needed to research further.

Rehabilitation Background Information

How is rehabilitation progress in stroke victims measured?

Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity

Point based system to assess motor function, sensory function, balance, joint range of motion, and joint pain

Motor function is based on 0-100 on each

Action Research Arm Test (ARAT)

Measure Upper Limb function

Grasp, grip, pinch, and gross movement

Finger joint flex and extension

How much force is generated in finger movement?

How will we measure accuracy?

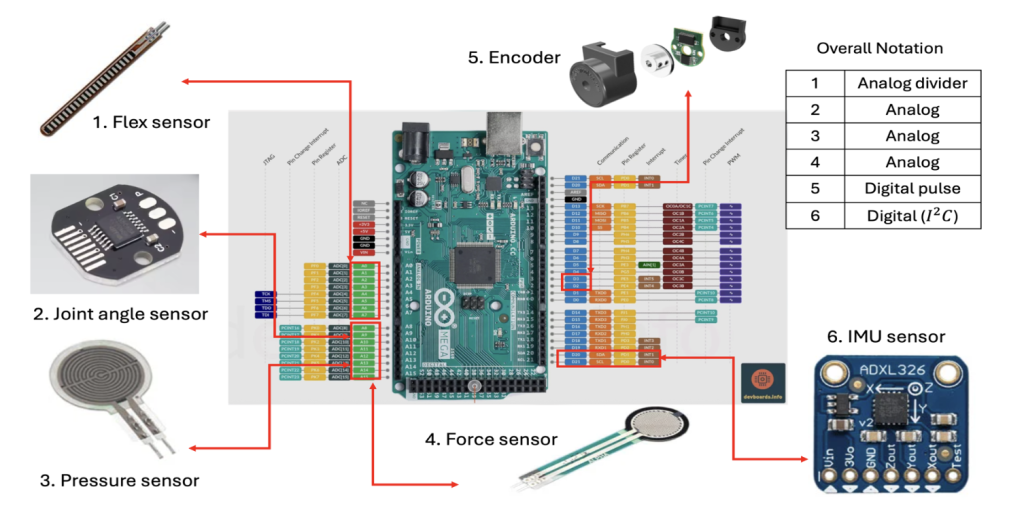

Type Of Sensors

Electronic Configurations

Diagram of Electronic Configurations

Pin Map

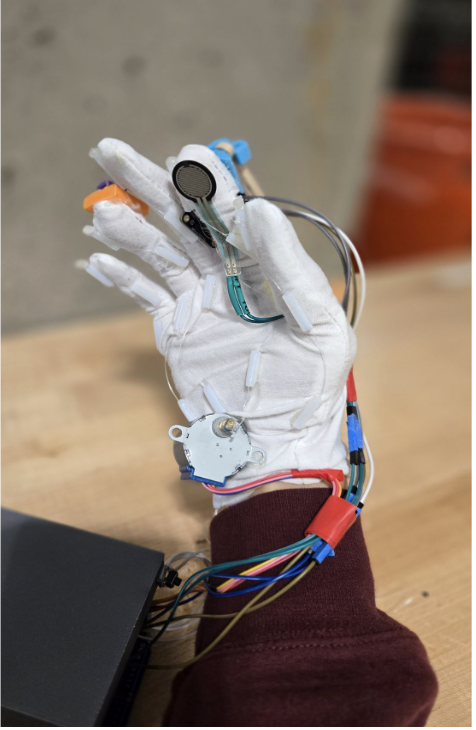

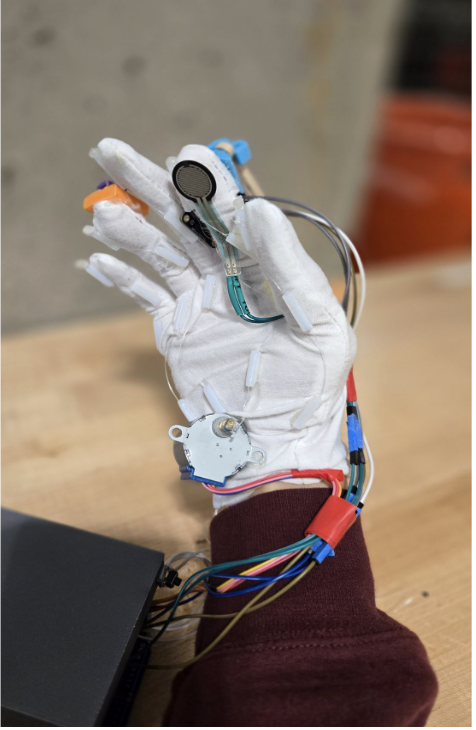

Throughout stroke rehabilitation, patients perform several hand exercises including grabbing objects and individual finger movements. These actions are meant to increase the range of motion the patient can perform on their own. Often the angles of the joints in the fingers are measured by a physical therapist to record and measure the progress of the patient throughout their rehabilitation process. Our glove aims to not only act as an exercise tool but also provide useful information for the patient and their physician. To achieve this sensors will be added to the glove to measure angles of the fingers throughout the patient’s exercises as well as on their own. Three sensors were added to evaluate which would most accurately record the angles of the finger: flex sensor, magnetic encoder, and a 9-DOF IMU. The flex sensor was placed along the top of the entire finger and measures changes in electrical resistance to measure a change in bending. The magnetic encoder required a second magnet and measured the changes in the magnetic field as the magnet rotated. This IMU had 9 degrees of freedom including a gyroscope, accelerometer, and a magnetometer in all three axes. Both the magnetic encoder and the imu were placed on the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) of the index finger.

Each of these sensors were wired to a perfboard then connected to an Arduino Mega 2560. An Arduino Mega was used to ensure there would be enough analog and digital pins for sensors and motors to be wired to each of the five fingers in the hand. The flex sensor was wired to its analog pin, 5V, and required a resistance bridge of 5Ω. The magnetic encoder and the IMU were wired to the ground, 5V, and the SDA and SCL pins for communication. After the sensors were wired correctly they were all calibrated. The encoder and the flex sensor were calibrated in the same way. The actual finger angle was measured with a goniometer at a straight position then at a fully flexed position. The raw output of the sensor data was recorded at these values as well. The data received by the Arduino was received and smoothed with an alpha value of 0.15 to ensure the natural structure of the data was preserved while removing excess noise that would interfere with the reading. Upon smoothing linear mapping was performed between the values for the finger when straight and when fully flexed so that the actual angle of the finger would be printed by the Arduino rather than the raw value. The IMU was calibrated by downloading the Adafruit_BNO055 calibration library. When using this script the IMU must be moved and rotated in all three directions and it will automatically calibrate. The calibration data is stored and reloaded so that no new calibration must be done. All calibration codes can be found on the GitLab for the project.

In addition to these sensors to record the angles of the fingers, a force sensor was added to allow the patient and their physician to record the finger and grasping strength. The force sensor was wired and calibrated in the exact same manner as the flex sensor and was placed on the fingertip of the glove.

In order to move the glove, initially micro gearbox DC motors were used because they were lightweight and small were preferable for the glove. These motors required the DRV8875 motor driver however, upon wiring and testing it was found that these motors did not have enough torque and power to effectively pull the string tendon to bend the finger. Instead the 28BYJ-48 – 5V Stepper Motor was used which provided twice as much torque and allowed the finger to bend when the fishing line was pulled. This motor required the ULN2003 motor driver board. To ensure that there would be no brownouts or sudden voltage drops the arduino was powered by a 9V battery while the motors were powered by four AA NiMH batteries which allowed the voltage to match that of the motor. The motor driver board was wired to the Arduino ground and the positive output of the battery pack. The battery ground was wired to the Arduino ground and the ULN2003 IN1, IN2, IN3, and IN4 were wired to the Arduino pins D8, D9, D10, and D11. The motor was controlled by a button connected to the motor ground and its own pin. When the button is pressed the motor will turn on or off. The motor speed and timing was adjusted so that when it is on the motor will reel the fishing line in to bend the finger then reverse to extend so that the patient and complete a full flexion motion.

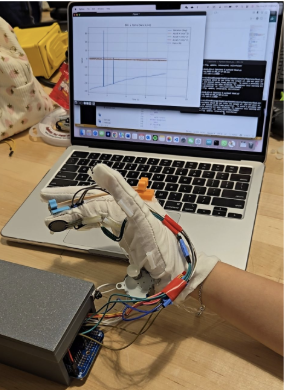

Wireless communication

This project implements an end-to-end communication pipeline that enables real-time transmission of multi-sensor glove data from an embedded wearable system to a computing platform, with optional integration into a ROS2-based robotic control framework. The design emphasizes low latency, reliability, and reproducibility for experimental data collection and downstream robotic applications.

Embedded Data Acquisition

The wearable glove integrates multiple sensors, including flex sensors, force-sensitive resistors (FSRs), a magnetic encoder, and an inertial measurement unit (IMU). An Arduino Mega 2560 is responsible for synchronized sensor sampling, basic signal calibration, and data aggregation. At each time step, sensor readings are packed into a structured data frame with a fixed field order to ensure consistent parsing on the receiver side.

Wireless Data Transmission

An ESP8266 module provides wireless connectivity and establishes a persistent TCP socket connection with the host computer. Sensor data frames are streamed continuously in a lightweight text-based (CSV-style) format. TCP was chosen over UDP to guarantee ordered and reliable delivery, which simplifies data alignment, logging, and experiment replay.

Real - time plot example

Link to GitLab:

3D Printed Exoskeleton Model Iterations

To prototype the glove, we printed out multiple exoskeletons from free online sources to support the motorized motion of opening and closing of the hand. The first structure above outlined the fingers and the palms to support the glove. However, the design structure was too flimsy to successfully 3D print the structure. It also did not leave room for flexibility and does not accommodate various hand sizes and shapes. Then, we moved on to the red model. This structure was sturdy, but it was too rigid for any flexible movement. We also experimented with mechanical assembly structures, but found that they were not suitable for pulling the fingers with our fishing line. We also tried various micro structures on the gloves, but finally settled on our exoskeleton structure.

Since none of the 3D printed exoskeletons fit the purpose of our glove, we decided to design our own 3D printed structures. We first designed hooks to fix the fishing reel onto a track on the bottom of the glove, but the hooks were too large and hindered grasping of objects. Instead, we reduced the size of the hooks and modified the hook to be modular to accommodate different sizes of hands for patients. Then, we decided to attach the fishing reel and line through a track of plastic tubes, and place the modular hooks on the dorsal surface with an elastic to aid moving the fingers to its original position.

Final Glove Product

The rehabilitation glove was designed to be lightweight and portable. It is also designed to prevent inhibition of natural movement of finger digits. It is composed of flex, force, and IMU sensors, with a motor driver to close and open the glove. The flex sensors are placed on the dorsal surface of the hand, over the proximal interphalangeal joints of the finger. The force sensors are placed on pads each finger on the palmer surface.

A fishing line is connected via small tubes on bottom sides for each finger. The line will be attached to the motor driver. As the motor driver rotates, it will wind the fishing line, causing tension and curl the finger towards the palm to simulate grasping motion. When the motor driver rotates the opposite direction, the tension will release as the fishing line will unwind and uncurl the finger. 3D printed hooks with elastic rubber bands are attached to the dorsal surface of the glove to aid in moving the fingers back to its original “flat” position. Users can adjust the elasticity by changing the socket of the printed part based on the length of the finger.

All of the electronics are housed in a box that can rest net to the patient as they perform their exercises. There is a button attached to the box that can turn the motor on and off when desired. The entire system is wireless and fully battery powered on only needs to be turned on to function.

Experimental Methods and Results

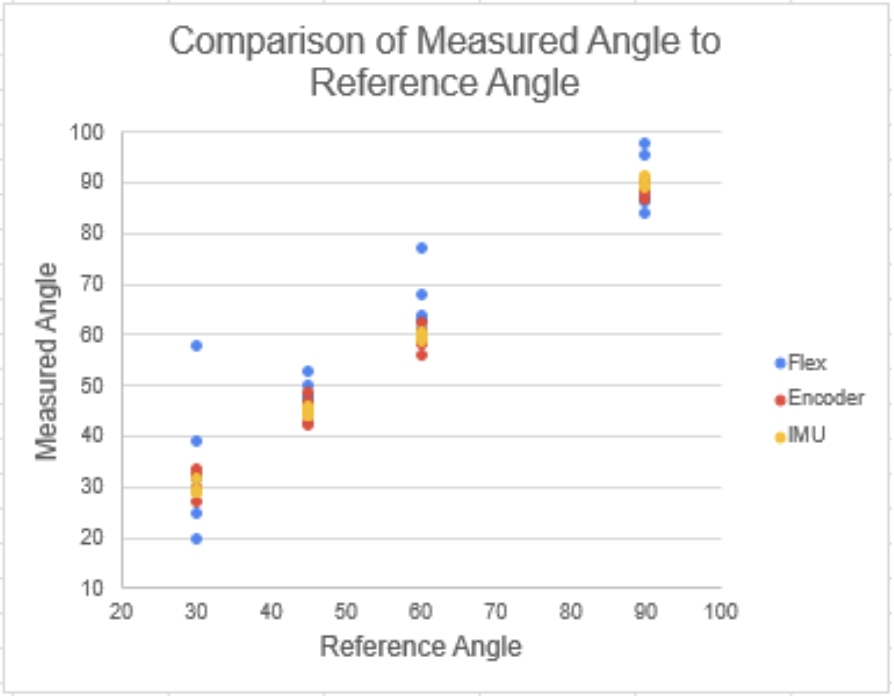

Joint angle measurements will be gathered from three sensors: flex, motor encoder, and IMU. The flex sensor will generate the degree of flexion, and the roll-pitch-yaw values generated from the IMU sensor will be converted to give angle degree relative to the position of the hand. The motor encoder gathers information about the rotation position of the encoder then converts the information into electrical signals, which can be calculated into joint angle values. The force is also measured for finger strength as additional rehabilitation measurement data. All the sensors are calibrated as listed above.

Each sensor was attached to the first digit of the glove. After the glove was calibrated, we tested 4 different joint angles at 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°. When the finger was bent at each angle using the goniometer as a reference, the joint angle measurement was recorded five times.

Joint angle measurements were recorded for each reference angle of 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°, as shown in Table 1. Percent error and Percent relative standard deviation was calculated for each sensor compared with the reference angles. The flex sensor gave the highest percent error for almost all reference angles except at 90°, where the percent error was 0.3%. The percent relative standard deviation for 30° for the flex sensor was 42.6%, indicating high variability between 5 measurements. For the motor encoder, the percent error for all four joint angles was less than 2%. However, the IMU sensor gave the lowest percent error for all reference angles with low variability between measurements.

Conclusions

Patients often face mobility loss in their extremities after suffering from a stroke, especially in their hands. Immediate rehabilitation through physical therapy is needed to regain mobility and function; however, due to shortages in physical therapists, care can often be delayed during the crucial recovery time. To help alleviate the rising demand of physical therapists, a robotic hand rehabilitation glove was designed and prototyped to aid in rehabilitation at home.

Three different types of sensors were tested: IMU sensor, flex sensor, and motor encoder. Each sensor was calibrated then measured against four reference angles of 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°. After testing, we determined that the IMU sensor gave the most accurate joint angle measurement compared to the four reference angles measured.

We were successfully able to create a prototype of the robotic hand rehabilitation glove that is cost-effective and provides real-time measurements of flexion and force. The entire system is battery powered so users do not need to be plugged into any power source. Additionally the entire system is wireless and can generate real time data that can be exported for review.

Future Work

To improve this glove in the future, first a stronger, more durable glove would be added. The current prototype is flimsy and is prone to tears, a new glove can provide more support for the mechanical systems and be safer for users. Additionally the mechanical design for the glove itself could be improved to provide more support for the user when bending their fingers. Improving these components could allow users who have zero mobility at all to still use this product. Upon improving the glove design for more stability throughout motions we would like to find stroke patients to test our product to obtain feedback data and fine tune the design specifically to the needs of stroke patients.

References

Bain GI, Polites N, Higgs BG, Heptinstall RJ, McGrath AM. The functional range of motion of the finger joints. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 2014;40(4):406-411. doi:10.1177/1753193414533754

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 24). Stroke facts. Stroke; CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Gladstone, D. J., Danells, C. J., & Black, S. E. (2002). The Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Recovery after Stroke: A Critical Review of Its Measurement Properties. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 16(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/154596802401105171

Kabir, R., Sunny, M. S. H., Ahmed, H. U., & Rahman, M. H. (2022). Hand Rehabilitation Devices: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Micromachines, 13(7), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13071033

Lambercy O., Dovat L., Gassert R., Burdet E., Teo C.L., Milner T. A Haptic Knob for Rehabilitation of Hand Function. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2007;15:356–366. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2007.903913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lyle, R. C. (1981). A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 4(4), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004356-198112000-00001

Ma, Z., Ben-Tzvi, P., & Danoff, J. (2016). Hand Rehabilitation Learning System With an Exoskeleton Robotic Glove. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 24(12), 1323–1332. https://doi.org/10.1109/tnsre.2015.2501748

Mirana Randriambelonoro, Perrin, C., Herrmann, F., Gorki Antonio Carmona, Geissbuhler, A., Graf, C., & Frangos, E. (2022). Gamified Physical Rehabilitation for Older Adults With Musculoskeletal Issues: Pilot Noninferiority Randomized Clinical Trial. JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies, 10, e39543–e39543. https://doi.org/10.2196/39543

Polygerinos, P., Wang, Z., Galloway, K. C., Wood, R. J., & Walsh, C. J. (2015). Soft robotic glove for combined assistance and at-home rehabilitation. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 73, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2014.08.014

Sandoval-Gonzalez O., Jacinto-Villegas J., Herrera-Aguilar I., Portillo-Rodiguez O., Tripicchio P., Hernandez-Ramos M., Flores-Cuautle A., Avizzano C. Design and Development of a Hand Exoskeleton Robot for Active and Passive Rehabilitation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2016;13:66. doi: 10.5772/62404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Tran, A. (2025, June 18). Best Stroke Rehab Equipment for Safely Recovering at Home – Home Recovery for Stroke, Brain Injury and More. Flint Rehab. https://www.flintrehab.com/stroke-rehab-equipment/?srsltid=AfmBOoosY2e452TmWmVvB68jFmnL2BV2MFGyazsQ85tDBGu52hd4Eai6

Xu, C., He, Z., Shen, Z., & Huang, F. (2022). Potential Benefits of Music Therapy on Stroke Rehabilitation. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2022(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9386095

Yang, K., Zhang, S., Yang, Y., Liu, X., Li, J., Bao, B., Liu, C., Yang, H., Guo, K., & Cheng, H. (2024). Conformal, stretchable, breathable, wireless epidermal surface electromyography sensor system for hand gesture recognition and rehabilitation of stroke hand function. Materials & Design, 243, 113029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.113029

Zarek, P., Ruttinger, C., Armstrong, D., Chakrabarti, R., Hess, D. R., Manal, T. J., & Dall, T. M. (2025). Current and Projected Future Supply and Demand for Physical Therapists From 2022 to 2037: A New Approach Using Microsimulation. Physical Therapy, 105(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaf014

Zhu, Z., Estevez, D., Feng, T., Chen, Y., Li, Y., Wei, H., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, L., Jawed, S. A., & Qin, F. (2024). A Novel Induction‐Type Pressure Sensor based on Magneto‐Stress Impedance and Magnetoelastic Coupling Effect for Monitoring Hand Rehabilitation. Small, 20(34). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202400797