Author: Pooja Mehta Page 1 of 2

This post seems fundamentally wrong

This week’s topics of focus, #1wknotech, Google Glass and Media Geology have all further affirmed my belief that we are doomed as a species to be slaves to technology (call me crazy). Starting with the #1wknotech, I think it says something to our dependence on technology that people use technology and social media platforms to talk about how it would be to not have these things. I find it a bit ironic and pointless that the whole premise of the project is to use technology as much as possible to hypothesize how it would be without technology. I think a better implementation of the project would be to go without technology for a week, then go back and reflect on the experience with the help of social media and technology.

The introduction of Google Glass and Media Geology into the mainstream of society will just increase our dependence on technology. As Google Glass picks up momentum, people won’t be able to just look at something without having a plethora of screens and monitors all around them. The idea of having to “look something up” will be foreign—rather, as soon as you need it, the information is right in front of your eyes. We will have the power to change the world around us. If you combine the power of the Google Glass and Media Technology, you can easily become the master of your environment. There will be sensors that indicate air quality, and Google glass will instantly show you if you’re in a good area to breathe or not. You can tell Google Glass if you’re uncomfortable with the temperature, and sensors in the surrounding area can adjust the temperature.

None of these seem like a bad thing, but my fear is about our reliance on them. If we depend on all of these resources to get us through our day to day life, what happens if it fails? Blackouts are not common, but they still happen…what happens if one day we lose all power? How will we be able to function as a society? Will we be able to? Maybe the reason we can’t fully do #1wknotech is because doing so would ruin us.

I thought that Ebocloud, while it started off confusing and a little dense, ended up being a really good book. While reading the novel, I focused mainly on the role and ethics of big data, the value of being online and the value of online connection as shown in the book. Big data plays a huge role in the novel. Not only do members of Ebocloud start off with all of their standard information online (name, birthday, interests, etc), they also share their interests, and that is used to group people into particular Ebo’s. Later on in the novel, we see the appearance of the dToo, which then gives the cloud access to people’s thoughts and actions, and allows the cloud to control it to an extent.

I think the world described in the novel has a big dependence on being online and being connected to others. For example, Jared bases everything he does on Ebocloud. He wants to build up as many karmerits as he can, and is one of the first in line to get his dToo. Matt is fully immersed as well, and even Ellie warms up to the idea. He is weary of it at first, but after meeting up with other Firewheels, he realizes that he really likes his “cousins”, and agrees to be a beta tester for the dToo, which he ends up loving.

This whole concept terrifies me. I agree that there is a value to being online and a value to being connected, but the extent to which it is shown in Ebocloud is a little much. The cloud has access to people’s brains and fields of vision and all sorts of crazy stuff. What if a bug is introduced into the program? What if it gets hacked? Who knows what kind of stuff people could be forced to do? The society seems to be pretty utopian, but I see the potential for it to get really ugly really quickly.

What is Google worth to us?

In response to our discussion on big data, siren servers and data as a product, I wanted to flip the discussion on whether or not Google should be using our data by seeing how much Google is worth to us. It would be a similar setup to PrivacyFix program that we did in class, but you would have to put in the information that you gather from Google and it would spit out the minimum cost to find the same information otherwise. This would involve a lot of algorithms and programming skills that I do not have, so for my project I was thinking of 1) finding a piece of information completely independent of Google and seeing how long it takes me/what it costs me to do so; 2) extrapolating on that to come up with a few cases, to kind of figure out the average cost of googling something or expand on how it changes for different situations; 3) using that to structure an ethical argument as to why it’s ok for Google and Facebook and all of these other programs to sell our data for profit. This will expand on our readings about Big Data, including “Big Data” and “Who Owns the Future,” and sort of tease out and augment their argument.

“Electronic literature is…a first generation digital object created on a computer and usually meant to be read on a computer” (Hayles 3). As Katherine Hayles states in her book, there is a new mode of literature coming about. Much as the change from handwriting to type brought about discomfort and fear, electronic literature is being met with some opposition. It is a very different experience than reading a book, even if it is an ebook. I personally am not a fan of electronic literature. For me, this was my first interaction with electronic literature ever, and it was a very disorienting and unpleasant experience. Unlike my experience with Daytripper, by Ba and Moon, I had no indication of how to “read” the project, and perhaps because of that I lost out on a lot of the merit of the piece and was not able to enjoy it.

One piece that was particularly unappealing to me was Dim O’Gauble. Initially, the theme was totally lost to me, and only after a little Google searching told me that this work is about a grandmother reflecting on her grandson’s visions of the future that came to him in nightmares. The presentation of the project itself is interesting. You start off by clicking in the middle of the panel, and the screen zooms in to reveal a small block of text, only four or five lines long. You then click on an arrow in the panel, and it takes you to another panel, again with a few lines of text, usually about a verse in a poem. You travel this way though the piece—some panels have text that appears and disappears, others have text that cycles through different words or phrases, and still other have hyperlinks that lead you to a completely new pane, where a video runs. These videos all showed a boy turned away from the camera, and each one was set to a different background. The backgrounds look somewhat like they have static, or have flickering shadows, like they’re lit by a fire. There are never any sounds or voices in these videos—only the background music and occasional temporary text appearing and disappearing. Watching this project with the “plot” in mind, I can see how the use of animations and the background graphics of the project convey the indecision and haziness that comes with recalling and processing memories, and how the videos could be of the grandson in the settings he sees in his dreams.

Dim O’Gauble does have a lot of literary merit to it. To paraphrase Hayles, electronic literature must have a foundation that is in accordance to what readers have come to expect with literature. It must have a “deep and tacit knowledge of letter forms, print conventions and print literary modes (Hayles 4). Electronic literature takes these foundational pillars and twists them, with the help of computer interfaces and programming, to the limits of our definitions, and reshapes what we think of literature as a whole. Dim O’Gabule does a good job of upholding this definition. The base of the project is a story that is told through text. Because all of the information we get is through text, and not through the videos or the music, it is indeed literature. However, it is not just text that is presented to you panel by panel, like Candles for a Street Corner. There is no way to take this text and simply type it out without losing a significant portion of the message that the author is trying to convey to you. Part of the message is how the text appears and changes, and if you were to read it all at once, rather than panel by panel, you would lose the process of understanding that the grandmother develops for her grandson. Additionally, the interaction that you must have with the project in order to appreciate the whole thing adds a level of intimacy with the text that simply isn’t possible with a book or a Kindle. You decide where to start, and the story only progresses if you choose for it to. The disappearing and changing text forces you to pay full attention to the project at the onset—you can’t simply skim over it and go back to look at it again, because there is some text that flashes briefly then goes away, even if you return to its home panel.

Regardless of the literary merit of the piece, it was not something that I enjoyed working with. For me, there is a certain pleasure associated with having a text in your hands and flipping through it (to this end, I do not particularly enjoy ebooks either). Even with online literature, you can print it out and get the exact same piece in your hands—the only thing that is lost is the necessity of a power cord and a few sheets of paper. With electronic literature, depending on the intricacy of the project, there is no way to do that. Candles for a Street Corner, a very early and simple piece, could be printed on a piece of paper, but it would lose the graphics and animation that help present it. Indeed, the piece has a link to a plaintext version of the poem, and it fully conveys the theme of the poem. Dim O’Gauble could have the text printed, but then it becomes a poorly written story about a hypothetical scenario of fear and confusion. An even more extreme project, Rememori would not be possible without the use of interactive computer interfaces. This project involves the audience to choose a persona, and then through that persona play an interactive game. As the audience clicks on the tiles to match them to each other, text appears, a short phrase that is the persona’s perspective on Alzheimer’s disease. If the text were to be printed on paper under all of the different personas available in the story, it would be a completely different piece of work, one that dosen’t have much resemblance to the original. For me, this reliance on interface severely compromises the durability of electronic literature as well. If I love a piece that I saw, and one day want to show it to my child, there is no assurance that the platform it is available on will be accessible. Paper is a sturdyobject that to me, is what literature should be conveyed on. While Dim O’Gauble is a piece that is sound from a literary perspective, I did not enjoy it and would be devastated if electronic literature went on to be the dominant form of literature.

Campbell, Andy. “Dim O’Gauble.” Dreaming Methods. The New River, 2007. Web. 23 Nov. 2014.

Hayles, Katherine. “Electronic Literature: What Is It?” Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame, 2008. N. pag.

Kendall, Robert, and Michele D’Auria. Candles for a Streetcorner. 2004. E-Literature. Born Magazine.

Wilks, Christine. Rememori. 2011. E-Literature.

Daytripper by Ba and Moon may just be one of the coolest things I’ve ever read. I have never read a graphic novel before, and it has been ages since I’ve picked up a picture book, so I forgot how much pictures can add to a novel. When going through and annotating my spreads, one thing that really stood out to me was how Ba and Moon focused on color and facial expression to really supplement the story line and add an element that just isn’t possible with a plain text novel. For example, the spread where Bras is learning about his father’s passing. In the first panel, we see Bras leave the hospital and find his mother outside, so we know where the scene is taking place. However, after that, Ba and Moon choose to remove the background details altogether, so all we see is Bras and his mother on a solid colored background. This forces us to focus only on their interactions and not be distracted by what’s happening in the scenery. Then, the scenery slowly transforms from yellow to blue as the scene unfolds. The colors are a reflection of Bras’ emotions—it starts off as yellow, surprise that his mother is here at the hospital, and then slowly blue is added as Bras senses that something is not right and his mood shifts form surprise to shock, and finally when he learns of his father’s passing, he is on a pure blue background, pure, unaltered sadness. Additionally, the focus on facial detail is incredible. Ba and Moon do an incredible job of highlighting the character’s facial features, especially their eyes. It is said that eyes are the best way to express emotion, and in the panel where Bras finally gets the news of his father’s death, the sorrow and shock in his eyes is undeniable—as an artist, I can attest to the level of skill necessary to illustrate such emotion. Each spread works in a similar way, as can be shown by the side notes on the annotated panels

I think all of these things, these simple yet powerful enhancers to the novel are all testaments to the allowances of graphic novels, and by showing the action, Ba and Moon make the text speak more to the audience than if they had simply described the scenes. This novel demonstrates that a picture is indeed worth a thousand words.

Moon, Fábio, Gabriel Bá, Dave Stewart, and Sean Konot. Daytripper. New York: DC Comics, 2011. Print.

I am worth $36 and change to Google. In order to be worth something, that means Google sells me or something I do to others. I am still here, in full ownership of myself—so Google sells something I do, and specifically, things that I do on Google and its partner websites. All of my searches, all of the websites I visit, everything I do through Google is data which the company can use and sell to other businesses for profit; therein lies my monetary value. But what does that mean, “sell my data?” Does Google have my entire history stored somewhere which it can then sell for a nickel a pop? Or does Google sell my privacy rights to other companies, who can then track what I do? I’m not confused about the ability to sell data. I assume it can’t be too hard to track what type of music I listen to, what kind of foods I like, what websites I visit, whatever, based on my internet searches. After all, the first place I go with any question is Google. I’m just wondering about how Google and other companies can put a value on my data, and what that means for data itself. The whole concept of buying and selling revolves around the notion of giving money in exchange for goods and services. Data is definitely not a service. I guess it is something that is produced and consumed, so therefore it could be classified as a good. I suppose that would be its medium as well—a consumer good. In terms of writing, reading and thinking I’m not so sure. I feel like if it is to have a role in these three areas, it would be in thinking, and not human analysis but rather data processing—kind of the way a computer program makes a computer “think” about certain data sets. In that sense data would be more like facts or input values, which can then be manipulated and modified to extract information. It really is fascinating that this is so relevant a topic that there are discussions about it, and enough of a discussion that me, with my $36 net worth, can contribute to them.

Brb hiding in a cave

http://po.st/q65x5v

https://privacyfix.com/start#welcome

My definition of a game, based off of is any action that involves tasks, has rules that direct how those tasks should be done, and has some sort of end goal to it. This end goal could be anything from gaining a certain number of points, to getting to the next level, to competing a certain task. A medium is, to me, a method of delivering information and supplementing the information that is trying to be shared by the author. It could be as dynamic as the internet, as stagnant as a book, as interactive as, well, a video game. Additionally, it could be appropriate in some scenarios and inappropriate in others, which is why you often see the same information presented in a variety of different mediums. Or, as Ian Bogost says, “we can understand the relevance of a medium by looking at the variety of things it does” (Bogost 3). I would classify games as a medium because games have the ability to supplement information with the affordances of the particular game layout. Some games do not augment the information, and are simply prized for their entertainment value—for example, Flow doesn’t really seem to offer much as an information platform. On the other hand, a game like Storyteller could be used to deliver information and allow the player to see scenarios differently than if it were to be read on paper, because they could control the players and potentially decide the outcomes of certain stories. I think most forms of information could be turned into a game. In fact, this very phenomenon is played out in elementary schools throughout the country. Kids learn their alphabets, hand washing skills, and multiplication tables all through the help of games. There are even apps that turn day to day activities into games, or use games as motivators. For example, the apps we talked about in class. There was one that would record the area you encircled while you ran, and then mark that area as your “territory.” You would have to keep running the same paths in order to keep your claim on your land. It turned the mundane chore of working out into a game, thus giving it a competitive edge and making it seem like a more appealing task.

I think we should study games, because games have a lot of potential. As technology advances and we get better graphics and an increased ability to incorporate biodata into games, the line between gaming and virtual reality blurs. Because of this I would say to study one is to study the other. Virtual reality is already used as an educational medium—pilots use computer simulations to practice taking off and landing without ever getting into a plane. They have a screen either in front of or around them, and controls that change their viewpoint based on how they move the controls. There are different difficulties of landings, and obstacles that the pilot has to maneuver around. If you put some sort of competitive aspect to it, like points or a goal, is it really any different than a game? No–in fact, adding the competitive aspect to it turns it into a game.

Now, in this argument, I am treating videogames as a subset of games, and use videogames as a term to describe traditional video games, cell phone games and computer games—basically any game that has a primarily digital aspect. Many papers that discuss the topic of games talk about video games. It is true that as technology becomes more integrated into our lives, video games will grow to encompass a bigger sector of games, and it is not unreasonable to say that it will eventually dominate it. Already there are children who don’t know what board games are, since they have only ever played on their tablets and other devices. I do see a future where games will become obsolete and will only be relevant in terms of videogames, but society will definitely lose something at that point. Like Bogost’s example of caterpillars—“If you remove the caterpillar from a given habitat, you are left not with the same environment minus caterpillars: you have a new environment, and you have reconstituted the conditions of survival” (Bogost 6). I think there should be a focus on studying regular games as opposed to video games, simply because the progression of technology is naturally taking us towards video games, and if regular games are pushed to the side, we lose a caterpillar in our environment. Additionally, with technology comes pros and cons, a point that is also mentioned in Bogost’s post. Gaming can be used as teaching and analytical tools, but it can also encourage laziness and distractions. Studying games and gaming can help steer it into a more positive light and find ways to utilize games to facilitate development and societal success, rather than a discouraged practice.

Games are an integral part of life, and life could be thought of as a game. It seems like something someone who is obsessed with video games would say, but it really has more of a philosophical, deeper grounding to it. Depending on where you are or what stage in your life you are at, your definition of “wining” changes. You “level up” as you go—you graduate college, you get a job, you start a family, you live a happy life. There are winners and there are losers, but we are all part of the same game of life—looks like Milton Bradley wasn’t too far off!

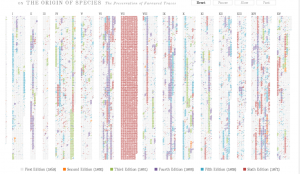

On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces is a digital humanities project by Ben Fry on the evolution of Darwin’s famous On the Origin of Species. It begins with three introductory written paragraphs which clarify the purpose of the project, give a couple of examples of significant changes in Darwin’s work across its six editions, and give credit to the sources, tools, and motivations behind the project, respectively. Under these three paragraphs lies the main media element in the project: a hyper minimized copy of Darwin’s work which can undergo a time lapse at two different rates which demonstrates the changes in Darwin’s work across its six different editions by color coding these changes.

The core conceptual content of Ben Fry’s project is that Darwin’s seminal work on evolution itself evolved in a substantial way throughout its six different editions. When we evaluate this thesis, however, we see that the thesis is not a contestable one, although it is both defensible and substantive (Galey 1). It fails to be contestable for the simple reason that anyone who is aware that Darwin’s Origin of Species went through six editions will recognize that it did go through such an evolution. This failure could have easily been remedied in a number of ways. Rather than simply presenting the data about how the book transformed, for example, Ben Fry could have analyzed this data. We get a very small dose of analysis in the second introductory paragraph when he points to the addition of “by the Creator” in the second edition of Darwin’s text and when he points out that the phrase “survival of the fittest”, inspired by a British philosopher, only appeared in the fifth edition of the text. Continuing this line of thought, it would be a natural extension of Fry’s work if he addressed which changes in Darwin’s work were merely matters of detail and which changes were significant conceptual changes. Another question that Fry could have analyzed is the immediate one that any user has after interacting with this project: what happened to section VII during the sixth edition? In the time lapse, it is clear that the entire content of the section is original to the sixth edition, so it is a natural question to wonder to what extent this change influenced the main conceptual core behind the Origin of Species. Another crutch the project has is that it only really relies on one source, Dr. John van Wyhe’s The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Additionally, it does not incorporate data from other digital humanities projects, and it suffers from a lack of links or annotations. The last hyperlink in the third introductory paragraph, which is found in the sentence “More about the project can be found here”, does, however, provide some interesting autobiographical motivation for doing this project. In it, he says that after completing the project, he came to a greater appreciation of Darwin’s original ideas and discovered that they were not in fact stolen from some of his contemporaries. Again, the reasons he came to this conclusion would have been an excellent piece to analyze.

The format and design that Fry used for his project is also somewhat of a mixed bag. As a positive, Ben Fry succeeded in making his thesis “experiential” by both color coding changes based on the edition as well as letting the user experience these changes through a time lapse that has the option of going at two different rates. Furthermore, these media elements were not at all used gratuitously, but they all have explicit connections to the conceptual core of his project. Additionally, the format and design were essentially digital; the time lapse for example could not have been done on a piece of paper. However, these positives are not unaccompanied by limitations. Users of this project will find it very inconvenient to identify what the edits actually are. The project does let one zoom in on a couple lines at a time by scrolling over the text, however it would be much more usable if the project let a user zoom in to individual chapters or paragraphs and see the edits in a more contextualized setting, rather than just zooming in on one line at a time. Changing this one thing could potentially have vastly expanded the audience of the project.

The academic integrity of the project is hurt by the fact that it only really had one source, and it also did not have any collaborators. He did succeed, however, in document his intentions for the creation of the project in the concluding hyperlink: he began the project to understand to what extent Darwin stole ideas from his contemporaries. The project is linked to by other websites occasionally, but only for the purpose of directing the audience to it rather than using it or analyzing it in any depth (see here and here). The work does not seem to use expert consultations, and it is not peer reviewed.

After looking through the criteria for a multimedia project, and applying the sets of questions given by Shannon Mattern, we would argue that this is not a multimedia project–it is a media project at best, and a glorified e-text at worst. That is not to say it is not a good project. According to Fry, “We often think of scientific ideas, such as Darwin’s theory of evolution, as fixed notations that are accepted as finished. In fact, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species evolved over the course of several editions he wrote,” and this project strives to show the evolution of the idea of evolution. He does a good job of demonstrating this through the use of processor, but that, along with the original text, is the only media he used. While it does repurpose the text by putting all six editions together and allow us to see the differences that a hard copy simply could not, we would argue that Fry left out a lot of things that could have been done with the project. For example, instead of just showing us the changes, embedding tags into the project that offer explanations or hypotheses for certain changes would make it much more informative and take advantage of the fact that this project has the entire knowledge of the internet available to it. This would also give more credit to the format of the project. As it stands now, while it is cool to watch the text change and grow, printing out the final result would cause no loss in information. If there were tags and other external resources embedded directly into the project, keeping it in a multimedia format would be necessary. But, after looking at some of Fry’s other projects it seems to us that most of his work is done with the intent of being displayed in print. So this project does do what Fry wanted, but it does not qualify as a multimedia project.

Mattern, Shannon C. “Evaluating Multimodal Work, Revisited.” » Journal of Digital Humanities. Journal of Digital Humanities, 1 Sept. 2012. Web. 21 Sept. 2014.

Fry, Ben. “Projects.” Projects | Ben Fry. Ben Fry, n.d. Web. 21 Sept. 2014.

Fry, Ben. “On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces.” On The Origin of Species. Ben Fry, 2009. Web. 21 Sept. 2014.

Galey, Alan. “Literary and Linguistic Computing.” How a Prototype Argues. Oxford Journals, 27 Oct. 2010. Web. 21 Sept. 2014