Death In Venice, Undying by Anna R

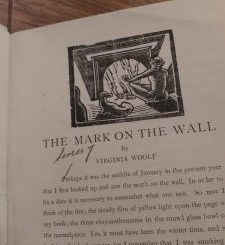

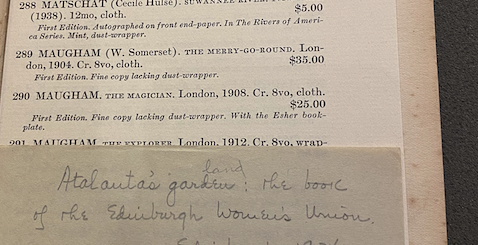

Thomas Mann’s Stories of Three Decades wears its age beautifully. Published by Alfred A. Knopf in New York in 1936, when the author was 51, its quilted, beige cover, taupe lettering, and minimalist green accent lines lend the collection a timeless quality. These earthy tones and the textured binding are reminiscent of papyrus. The full effect impresses upon readers that the collection is both worldly and elevated; original yet seasoned. Perhaps unwelcoming to an average reader, this hefty volume would find its ideal home in a refined library or study. Mann’s name stands out prominently on the front cover, positioned above the title in larger print. The translator’s name does not appear until the title page. This emphasis on Mann indicates that he was a widely known and well established author when this edition came to market – clearly the publisher believed his name would draw potential customers, and perhaps thought adding the translator’s name would detract from its impact.

The table of contents lists twenty four works and their years of publication, which span from 1897 to 1929. Death In Venice, which was published in 1911, is the fourth latest work in the collection. Visually contextualized within Mann’s career, it’s clear to see that Death in Venice was published when Mann was a mature author. It’s interesting to note that, like Mann, Aschenbach was middle aged and had achieved notoriety as an author when Death In Venice begins. These similarities inspire a more autobiographical reading of the text: Aschenbach, as we learn early in the narrative, has become intellectually ossified, and perhaps Mann himself was struggling with his identity as an artist or his relationship to fame when he wrote the novella. Perhaps his real experiences seeded Aschenbach’s character and conflict.

Stories of Three Decades features the same translation of Death In Venice by H.T. Lowe Porter that we read in class, but it differs from the first translation I read by Stanley Appelbaum, which came to market in 1995. One of the most prominent differences between the two versions is in punctuation. Porter tends to break up long sentences into shorter ones, whereas Appelbaum does not. Consider part of one of my favorite sentences in Appelbaum’s translations: “… private carriages were stationed; from there, as the sun was setting, he had taken a homeward route outside the park across the open meadow; and now, since he felt tired and a storm was threatening over Föhring, he was waiting at the Northern Cemetery…”(1). This long, serpentine sentence reads quite differently from Porter’s version: “… with its fringe of carriages and cabs. Thence he took his homeward way outside the park and across the sunset fields. By the time he reached the Northern Cemetery, however, he felt tired, and a storm was brewing above Föhring; so he waited…” In Appelbaum’s version, there is more emphasis on the highly significant sunset, which is somewhat lost in Porter’s version. In the phrase “sunset fields,” it’s unclear if the sunset is real, or some sort of metaphor. And the fact that Porter split this sentence into many chunks changes the cadence of the language significantly. Death In Venice is intentionally written in long, tortuous sentences, in part to mock Aschenbach and his concept of art. This layer of meaning is lost in Porter’s version. Porter also places the “Northern Cemetery” at the beginning of a sentence, instead of at the end of a clause. This choice takes away some of the impact and surprise that readers experience when it is revealed that Aschenbach has taken refuge at a cemetery, which is a highly symbolic setting. Ultimately, while Porter’s version is more readable, I believe Appelbaum penned a stronger translation, though it’s impossible to know without reading the original German.

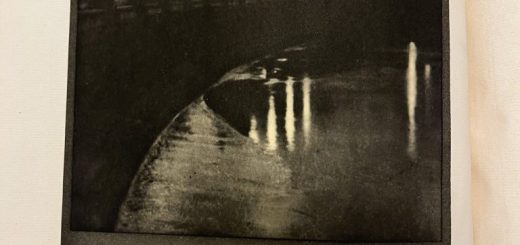

More than anything, seeing this venerable copy of Stories of Three Decades prompted me to consider whether art truly endures through time. Death In Venice is principally occupied with the way age ravages youth and beauty. In a way, books do have the power to preserve people and ideas through their pages – Mann’s works still survive after decades. But have they truly remained the same? Passing through countless hands, undergoing numerous translations, their messages are as dynamic as their readers. In its narrative, Death In Venice tells a cautionary tale, as Ascehnbach’s worship of static, ideal art feeds deterioration and death. The history of Death In Venice suggests an alternative to Aschenbach’s concept of perfection. Ultimately, literature is preserved through transformation, as passionate readers keep its beauty alive. Great art is never still; it grows with age.

Works Cited

Mann, Thomas. Death in Venice. Translated by Stanley Appelbaum, Dover Publications, Inc., 1995.

Mann, Thomas. Stories of Three Decades. Translated by H.T. Lowe-Porter, Knopf, 1936.

Recent Comments