Atalanta’s Garland: An exploration of the spectrum of Scottish Femininity by Sawyer L.

Atalanta and Hippomenes in the footrace – Guido Reni

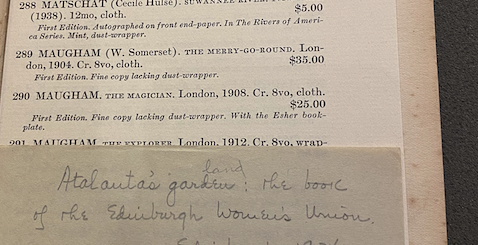

Part of what stood out to me when I chose this Object, as the stereotypical Latinist that I am, was the title: Atalanta’s Garland. For a book for the Edinburgh University Women’s Union, I thought the content of the journal would be straightforward. Atalanta is properly one of the earliest feminist heroines in the Greek mythos, spending most of her time in canon as being defiantly celibate in spite of her father’s and society’s wishes otherwise. Atalanta pledges herself as a celibate huntress to the Goddess Artemis, becoming almost an unrivaled huntress and uncontrolled by Greek patriarchal norms. Eventually, society catches up to Atalanta, and she succumbs to a compromise with her father, where she agrees to marry anyone who can beat her in a foot race and kill everyone that loses to her in the race. Hippomenes, with the help of Aphrodite, uses golden apples to distract Atalanta and wins her hand in marriage, ending Atalanta’s defiant stance in celibacy. With this myth coupled with the Edinburgh University Women’s Union, one expects a suffragist, early feminist attitude throughout the journal.

Opening the piece reveals instead a rather contrary image: the frontispiece of the triptych “Motherhood,” and image depicting a mother cradling her child on the Scottish  borderlands, a piece which the Scottish National Galleries give the tag “Celtic Revival.” Viewing the authors listed throughout the table of contents confirms that “Atalanta’s Garland” places strong emphasis on including two types of writers: those with strong and significant ties to Scotland and its culture like Hugh MacDiarmid, Cecile Walton, and Rachel Annand Taylor; and Anglo/Scottish writers, female or male, who write about the feminine and familial experience, including Hilaire Belloc, Walter de la Mare, Fredegong Shove, and Irene Forbes-Mosse. Included among the group of preeminent female authors are Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, whose works are at the beginning of the book, providing what appears to be a grand summary of the books contents.

borderlands, a piece which the Scottish National Galleries give the tag “Celtic Revival.” Viewing the authors listed throughout the table of contents confirms that “Atalanta’s Garland” places strong emphasis on including two types of writers: those with strong and significant ties to Scotland and its culture like Hugh MacDiarmid, Cecile Walton, and Rachel Annand Taylor; and Anglo/Scottish writers, female or male, who write about the feminine and familial experience, including Hilaire Belloc, Walter de la Mare, Fredegong Shove, and Irene Forbes-Mosse. Included among the group of preeminent female authors are Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, whose works are at the beginning of the book, providing what appears to be a grand summary of the books contents.

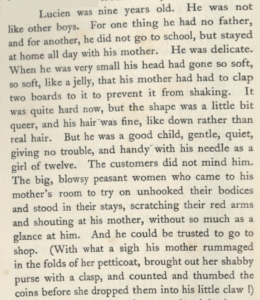

While Mansfield’s most famous work, “Garden Party,” paints the dynamic between the upper class and their willful ignorance and thus bliss of the struggles of the lower socioeconomic echelons, Mansfield’s sketches here paint a different story, stories of motherhood and the struggles of being a mother in the lower class. There are no men in her stories, only dyads of a children and mothers. The mothers are working class: one a dressmaker who is relentlessly derided by her clients, the other can only afford second hand prams for her baby. The children live in undesirable conditions: one must sell newspapers to make money for his family and his mother had to place his head between boards herself to make sure his soft head developed right, the other lives in a basement, with pale skin, he’s never hungry, and his grandmother warns of taking him out into the city air. They are written mechanically, cataloguing this experience with much less emotion and exuberance than Woolf’s piece. Woolf follows the experience of instead a group of university women, describing the experiences of walking through the serenity of campus, as well as the themes of a changing youthful womanhood, exploring both social and sexual loosening as part of growing up and being a young woman.

The title combined with the frontispiece, Mansfield combined with Woolf, both paint this book as exploring the idea of femininity, praising motherhood, bringing light to the struggles of class in the life of a mother, showing how femininity changes with age and the fact that this maternal, domestic femininity and the independent, suffragette femininity of the 20th century can in fact coexist.

Recent Comments