The Ethnography Workshop hosted Sowj Kudva for a seminar titled “Conversations on Documentary: How Form Influences Function.”

“Why can’t people see the construct? What is seen, and what is not, in the final film?”

Prof. Kudva’s seminar focused on the links between production culture, media literacy, and documentary theory. How is it, they opened by asking, that a reality TV producing team who set out to ridicule fantasies of wealth ended up transforming Donald Trump into a serious national star? How can we explain the gap between what the editors thought they were building and what the audience perceived? More broadly, what would it take to foster critical media viewership, and what are the stakes of this effort, pedagogically, politically, and ethically?

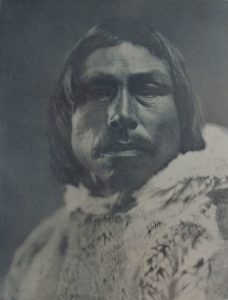

Prof. Kudva described the permeable borders between the worlds of advertising, politics, and entertainment–to take one example, the same production company that designed advertising for a disastrous music festival, Fyre, later produced a Netflix documentary about that festival’s failures, and is now creating memes for the Michael Bloomberg presidential campaign. (More info here and here). This is not new: in the early 20th Century, a French fur company financed Robert Flaherty’s film, Nanook of the North, which soon took on canonical status as a pioneering documentary and ethnographic film. The films origins in advertising, however, and the ways in which this influenced its depictions of life in the Arctic, have received less attention.

“What is at stake in documentary today is not so much truth, as trust and betrayal.”

Prof. Kudva drew from a rich body of scholarship in documentary and film theory around questions of representation and artifice and the role of documentation in the development of state power. Some of the seminar’s most compelling insights, though, stemmed from Prof. Kudva’s own personal experience working in film and TV. Their emphasis on production cultures, or the kinds of relationships that develop behind the camera and in the editing room, grounded and complicated the theoretical conversations.

The seminar ended with a conversation about how to merge film/media and ethnography, and a reflection on the importance of teaching critical media literacy to students. While younger generations are often assumed to understand media, Prof. Kudva highlighted the crucial difference between knowing how to use something and understanding how it works. People of all ages need to be taught how to understand media–film, TV, memes, social media, advertising–as constructs, ones with messaging both overt and concealed. One of the ironies of much contemporary documentary/reality TV production is that the apparatus of filming is visible–mics are in the shot, the producers talk to subjects or directly to the camera–and yet showing this artifice helps to shore up viewers’ trust in the film. Viewers become more gullible, not less, the more they are reminded that they are watching a film. “What is at stake in documentary today is not so much truth, as trust and betrayal.”

UPDATE! Prof. Kudva adds that “certain mediums that purport to represent reality are more obvious in signaling creativity, expression, construct, purpose, and strategy. Peasantries consigned to the early state were highly aware of the meaning of cuneiform documents and burned down records offices to ‘blind’ the state. Comics signal creative representation because the process of drawing—the line, the mark of the author—is visible. The written word looks and feels nothing like reality—a clear technology in which connotation and interpretation weigh heavily. Audio is missing the visual. Both audio and the written word require participation from the reader/listener to imagine the ‘missing’ pieces of those realities. Conversely, video and film and photography seem like an indelible mark of something that was. There’s no denying what was captured (the word ‘captured’ itself takes on a fascinating meaning). Video as a mark of reality feels true and compelling and tends to obscure concepts of perspective and creative expression, even when those films/videos are cut up and rearranged and create another form entirely.”

“This is not a workshop in how to draw,

“This is not a workshop in how to draw,