Like many cities worldwide, Beijing is undergoing a rapid urban renewal movement, catapulting the city and its profound history into an era of metropolitan globalization. With globalization, urban characteristics featured in different regions have become more homogenized, while the traditional cultural symbols that represent the heritage of a city are disappearing. Stripped of memory and tactile features, uniform in style, and obeying standardized rules that are independent of region, these homogenous architectures represent the emergence of a function-based, rule-based, industrial approach to urban structure. Urban planners and government officials consider this approach as modern.

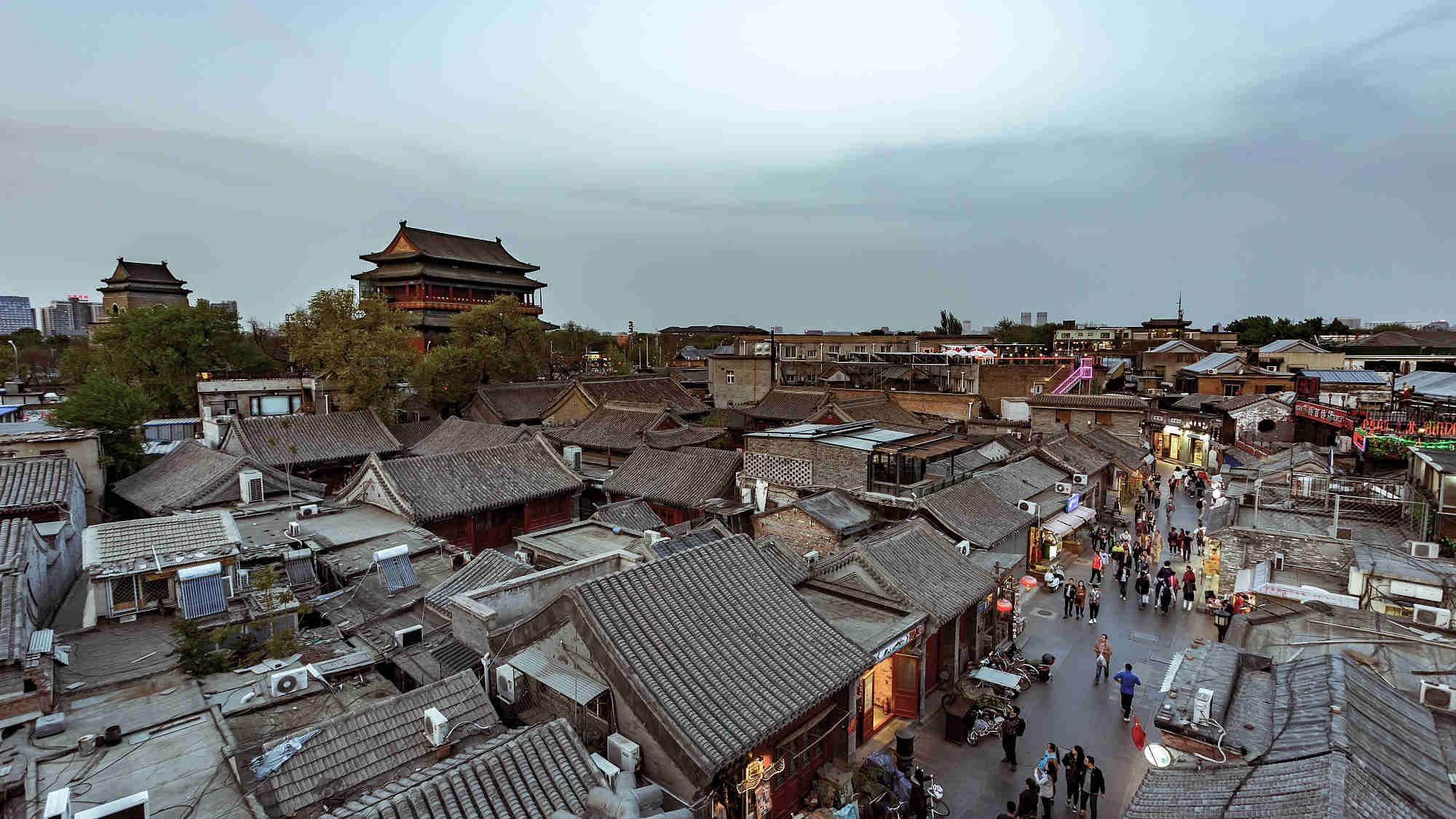

From a public health and safety standpoint, tearing down unregulated places that are in violation of legal codes is reasonable to an extent, but the citywide cleanup appears to be adopting a one-size-fits-all solution that diminishes the city’s vibrant local businesses and cultural spaces – spaces for different ideas and discussions. Giving in to the pressure of economic development and the political decisions to transform Beijing into a “modern world-class city,” Beijing’s urban modernization progress comes at a cost to its historical and cultural heritage. Hutongs (胡同) – the traditional grid-like living quarters of common people in Old Beijing – are one of the many cultural heritages that struggle to fit into the fast-changing urban context.

90% of the original 8000 hutong neighborhoods – the traditional grid-like living quarters in the old part of Beijing where I had grown up – had either been leveled to make room for homogenous apartment complexes or had their local businesses bricked up and turned into identical malls.

Although there is no straightforward solution to a conundrum like urban transformation: At the center of urban modernization lies one country’s changing definition of legality (of whether structures could be eliminated for unauthorized land use), of freedom and authority, of inclusively and exclusivity, and of progress and modernity. Still, cities like Beijing are being wrested from their locals and reconstructed at a startling rate. History simply won’t document itself unless we become cognizant of the values in the disappearing and often marginalized cultures under the context of modern globalization.

People make changes before policy does. While there’s still a chance, we ought to take the initiative to help document and revitalize the disappearing communities in Hutongs. This digital storytelling project will not only help demonstrate how digital technology can help marginalized culture – the culture of the political powerless – stay present and relevant; it can also show how the digitization of cultural heritage enables communities to be co-producers of knowledge in documenting history, another side of history that is equally important.