The thing about exile is that it is far away.

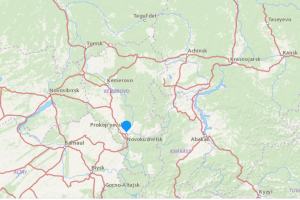

Dostoevsky was sent to Semipalatinsk as a common soldier after his release from the Omsk fortress on March 2, 1854. The city is now called “Semey,” and it is now in Kazakhstan. Find Omsk in the map (under the “A” in “Russian Federation”) and slide down to the southeast until you see the second little red airplane. Like Omsk and other key locations on our journey, Semipalatinsk is on the Irtysh River.

Outside Dostoevsky circles, Semipalatinsk is best-known as a nuclear weapons testing facility, and the location of the first Soviet nuclear bomb test in 1949. For us Dostoevsky fanatics, though, its key attraction is its Dostoevsky Museum (https://www.fedordostoevsky.ru/museums/semipalatinsk/. In normal circumstances (whatever that means), this would put the town squarely on my itinerary. But not only do you need to veer wildly off the main route (whatever that is); you also have to get a visa to enter Kazakhstan. I am not proud of this, but I chickened out.

Instead, I decide to follow a love story.

This means a significant detour from the Trans-Siberian, also, I might say, not for the chicken-hearted, to the city of Novokuznetsk (formerly Stalinsk, and before that, Kuznetsk). A nice straight line would take me from Novosibirsk to Krasnoyarsk. But down to Novokuznetsk it is quite the zig-zag: a night train from Novosibirsk, a few hours in Novokuznetsk, and then back on the next night train to Novosibirsk. Seems arduous, but compared with Dostoevsky’s travel from Semipalatinsk to Kuznetsk by dusty horse carriage, it’s nothing.

Your train arrives at 6:00 am. Too early for breakfast. You’ve figured, OK, let’s get oriented and find the museum, then we can sit and have some coffee nearby for a couple of hours before our date with the muzeishchiki after the museum opens at 11:00.

There’s plenty of time, so why not walk? A half-hour on the hoof down a long, chilly, gray avenue makes it clear that Novokuznetsk is larger in reality than it seemed to be on the map. So you subject your cell phone to a vicious beating, and then set to learning about public transit. It’s not that hard, really.

Personally, I love transit systems that include conductors who take coins and can answer questions.

Eventually, after a very long spell of gazing out the window at the broad gray avenues of Novokuznetsk (a landscape ominously devoid of eating establishments), I am deposited near this church. Turn your back to it and look across the street:

Progress! Now for that coffee, a muffin, a dose of wi-fi, the New York Times on my iPad, a nice little dip into the WC….

HA HA HA HA HA HA HA HA!

There are some industrial facilities, a couple of storage lots, a bit of what could be called traffic at 7:30 a.m. (trucks, and and a couple of guys walking on the side of the road in weathered work clothes, carrying what appear to be lunch bags). A car or two. The barking of invisible dogs.

It dawns on me that there will not be coffee, or food. Nor will there be even a place to sit down, for it is muddy on Dostoevsky Street. I try not to think about what I must look like to the natives, train-disheveled, bespectacled, bewildered, scowling at my cell phone.

One good thing; my (OK, all right, our) navigation is good:

Looks pretty closed up–after all, it is 8:00 on a Saturday morning. Three hours to opening. I could kind of lean on the wall for a couple of those hours, I guess. Or do a Dmitry Karamazov.

I choose the latter. Right about where you see my big-city gray bag hanging on the palings, I make my move. A person of my age and dignity level really shouldn’t be clambering, but after some huffing and puffing and a couple of snags, it works. I’m in!

I dust myself off, neaten things up on my person, prowl the yard, and reconnoiter.

Footsteps…

A man walks through the gate. It was not locked.

It is Alexander Evgenievich. Alexander Evgenievich is the night guard. He does not shoot me. Instead he gently walks me into the (unlocked) door of the museum and introduces me to Olga, who is sitting quietly there behind the reception desk. He says to Olga, “feed her.”

Olga doesn’t seem to notice my bedraggled state, nor the fact that I have just broken into the Dostoevsky Museum. She takes me by the hand and walks me to her cozy house down the street. Oladi, fresh ham, vegetables, and hot tea magically appear. I have fallen down the rabbit hole. Time, which 15 minutes ago was a terrible burden, opens up infinite possibilities at the place Russia does best: the kitchen table.

Once calm has been restored, and we have shared life experiences, and I have savored this sublime breakfast, Olga walks me back to the Museum.

There she hands me over tenderly to the museum’s Deputy Director for Research Elena Dmitrievna Truk han, who takes me through a couple of special exhibits in the main building. One of these displays artifacts and photographs of theatrical productions of Dostoevsky’s work done here by visiting directors. I am lucky to catch the exhibit, which is to be taken down TODAY. Even better, I meet the photographer, Vladimir Semyonovich Pilipenko, a kind and very alert observer who has traveled all over Russia taking pictures. He’s not about to stop today. Indeed, Vladimir Semyonovich’s photos will soon appear in a report about our day together with Elena Dmitrievna at the museum. http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/vizit-prezidenta-mezhdunarodnogo-obshhestva-dostoevskogo.html

han, who takes me through a couple of special exhibits in the main building. One of these displays artifacts and photographs of theatrical productions of Dostoevsky’s work done here by visiting directors. I am lucky to catch the exhibit, which is to be taken down TODAY. Even better, I meet the photographer, Vladimir Semyonovich Pilipenko, a kind and very alert observer who has traveled all over Russia taking pictures. He’s not about to stop today. Indeed, Vladimir Semyonovich’s photos will soon appear in a report about our day together with Elena Dmitrievna at the museum. http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/vizit-prezidenta-mezhdunarodnogo-obshhestva-dostoevskogo.html

The other exhibit is a charming collection of children’s art inspired by the great children’s writer and poet Kornei Chukovsky.

The children have done collages and paper sculptures of Chukovsky characters. Here, as elsewhere on my travels, I’m deeply impressed with the Russian emphasis on arts education, and with the ways museums are reaching out to children, not just as places where they can learn about famous people, places and events, but where they can interact with history and literature, and, importantly, create art themselves.

Yes, science is important. Art is equally important, and you need it for your soul.

Dostoevsky made three trips to (pre Novo-) Kuznetsk, spending a total of 22 days here, all in pursuit, and finally conquest, of Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, whom he married in Kuznetsk in February of 1857. He had met her previously in Semipalatinsk, before her husband was transferred here. Then her husband died here….

Dostoevsky made three trips to (pre Novo-) Kuznetsk, spending a total of 22 days here, all in pursuit, and finally conquest, of Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, whom he married in Kuznetsk in February of 1857. He had met her previously in Semipalatinsk, before her husband was transferred here. Then her husband died here….

1st visit: 2 days in June 1856: during this first visit to Kuznetsk, Dostoevsky learned that he had a rival for her hand (Nikolai Vergunov);

2nd visit: 5 days in November 1856: having received his promotion to the rank of ensign (praporshchik)– he came to make an official proposal of marriage to Maria Dmitrevna;

3d visit: 15 days in January-February 1857: during this visit he married Maria Dmitrievna in the Odigitrievskaya Church, and spent the first days of his married life before returning with her and her son to Semipalatinsk.

Just down Dostoevsky Street from the museum’s main building, you can visit the house of the tailor Dmitriev, where Maria and her first husband Alexander Isaev rented a room. Wonder what she would have thought if she could have known her house was going to be on Dostoevsky Street? Wonder if anyone thought of naming it Maria Dmitrievna Street?

After posing this question, I received a fascinating answer from Elena Dmitrievna. Turns out, since the house technically did not belong to Dostoevsky, for years officials refused to allow a museum to be opened here. Only with the devoted efforts of local enthusiasts, with the support of the Dostoevsky Museum in Moscow, not to mention the sheer force of historical memory, did the museum finally open in 1980. The curious can read the full story here:

«Додумались» (в плохом смысле) чиновники, работающие в культуре. Очень долгое время они не давали открыть музей Достоевского в Новокузнецке, всячески препятствовали этому, называя дом не «Домиком Достоевского», как зовут сейчас его жители Новокузнецка, а Домом Исаевой, Домом портного Дмитриева. Их аргумент был «железным» и непробиваемым: «Не в каждом доме, где у писателя случился роман, надо открывать музеи».

Такой узкий краеведческий подход к событию (без культурного и литературного контекста) сделал своё грустное дело: открыть музей в Новокузнецке удалось только в 1980 году – то есть спустя 130 лет (!!!) после событий в Кузнецке. Вообще удивительно, как это удалось сделать! Если бы не помощь руководства музея Достоевского в Москве, если бы не местные энтузиасты-краеведы Новокузнецка, если бы не человеческая память, этого бы вовсе не случилось. И тогда еще одно место, связанное с жизнью Достоевского в Сибири, навсегда было утрачено.

Anyway, the house–the museum–is beautiful.

Elena takes me through the house. It is not an ordinary museum; rather it offers a kind of adventure, a  three-dimensional experience or even performance that loops in the story of Dostoevsky’s courtship of Maria with the larger story of the way his time with her influenced his writing. Novokuznetsk is a Dostoevsky city because of Maria’s story. Elena tells me this story, leading me from room to room. Vladimir Semyonovich is with us.

three-dimensional experience or even performance that loops in the story of Dostoevsky’s courtship of Maria with the larger story of the way his time with her influenced his writing. Novokuznetsk is a Dostoevsky city because of Maria’s story. Elena tells me this story, leading me from room to room. Vladimir Semyonovich is with us.

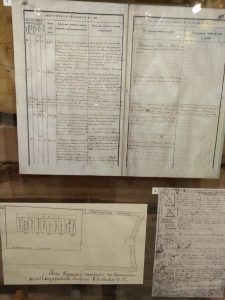

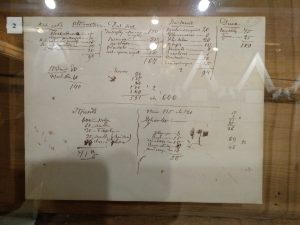

The diorama shows what Kuznetsk looked like when Maria lived here. The different rooms each offer a

part of her story, display documents and artifacts related to her relationship with Dostoevsky, and offer connections to his works. Here, for example, are copies of documents registering witnesses to their wedding ceremony, and Dostoevsky’s own scrawled lists of wedding expenses he had to cover. Elena is an active scholar herself, and works in archives to fill out the pictures relating to these years. For example, she found a document recording that Maria Dmitrievna had served as godmother of a baby (of the local citizen Petr Sapozhnikov) during her time in Kuznetsk. And, it turns out (as other scholars discovered), Maria Dmitrievna served as godmother to another child in that family AFTER her marriage. So the question stands; did Maria Dmitrievna and her husband (?!) make another visit to Kuznetsk?! The research continues.

The displays remind us of the ways Dostoevsky drew upon Maria Dmitrievna’s personality when creating characters such as Crime and Punishment‘s Katerina Ivanovna Marmeladova, and even Nastasia Filippovna of The Idiot. I take a quiet minute to ponder what it is, anyway, that writers do with life experience… Back in the museum, Dostoevsky’s famous meditation on the impossibilty of shedding the ego–written by his wife’s deathbed–“Masha is lying on the table,” is exhibited here on the wall.

.

.

One emerges from the museum full of impressions and thoughts about what life was like for Maria, and about why this person, time, and place were so formative for Dostoevsky’s life and works.

Elena then walks me around Novokuznetsk, to buildings that were standing during Dostoevsky’s time,

and to the town’s major attraction, the hilltop fortress, which in addition to its historical value, offers a beautiful view over Novokuznetsk:

We visit a newly renovated church (glimpsed in the photo above), and a newly built chapel by the train station.

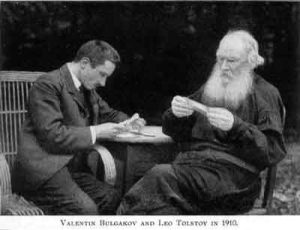

Tolstoy fans will appreciate the fact that Valentin Bulgakov, the writer’s secretary during the last year of his life, was from Kuznetsk. The name is familiar to anyone who saw the recent movie about Tolstoy’s last year, The Last Station, which draws on Bulgakov’s memoirs. On a longer visit I’d definitely visit the district school where Bulgakov’s father served as inspector–now a branch of the Novokuznetsk Ethnography Museum. Elena shows me the monument to him and Tolstoy: “Teacher and Student” (Учитель и ученик).

But let us not get distracted. Check out the Novokuznetsk Dostoevsky Museum’s website and many activities, including a virtual tour of an earlier iteration of the museum. And recently specialists in 3D graphics have produced a new virtual visit to the museum’s permanent exhibit, “A Guide to Novokuznetsk”: read about it here: http://www.dom-dostoevskogo.ru/novosti/3d-dostoevskij.html

Here’s the actual tour: http://vrkuzbass.ru/muz/nvkz/fmd/

And more! Check them out:

http://eng.md.spb.ru/dostoevskij/drugie_muzei_pisatelya/kuzneck/

https://www.fedordostoevsky.ru/museums/novokuznetsk/

http://dom-dostoevskogo.ru/muzei_dostoevsk/index.html

Take my word for it, Novokuznetsk has a lot to offer, and not just to Dostoevsky fanatics like me.

I am nurtured, mind, body and soul. But I cannot stay….there is a train to catch.

Leave a Reply