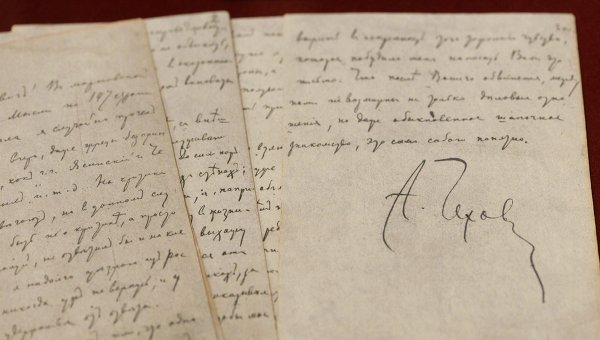

There was so much excitement in the Chekhov Post office that I didn’t feel I could go on. How seductive it would have been to sink down on that bench under the old post box inside and spend the afternoon there brewing thoughts. Mostly about how all writing is really just a subset of letters to friends.

Not all writing, not the stuff you have to send to your lawyer or boss, or applications, reports, recommendations, tax returns, appeals, parking ticket appeals [ahem, Duke], and the like. The hell of it all is that now these kinds of things have to be done on some sadistic corporation’s “easy to use” online platform. Some people around here (and by now, “here” is a dingy hostel in Kazan, Tatarstan) would prefer to write their blog in pen in one of those wonderful vinyl Russian notebooks with graph-paper grids, embellishing it with little drawings and smiley faces, with tickets, postcards, and other riffraff scotch-taped in.

Once we’ve taken care of all the unpleasant and practical writing that we have to do to ensure we stay employed, or don’t get thrown into jail or put out to debt collectors, that kind of stuff, then it’s time to do the good kind of writing, fiction, say, or letters to friends. And it turns out that there is some joy in embracing the fact that you are writing to friends–even if you don’t know them.

Now if I had followed my instincts to stay on that bench there in the Chekhov Letters Museum, I would maybe have had some deep thoughts, even sublime ones, but at the same time I would have been turning myself over to organic forces of inertia, gravity and decay. These forces are more than real; they are in fact Russian literature’s great master plot (and possibly the source of its inspiration). Oblomov lies in the grass, doing what he does best, which is nothing, and watches ants rushing to and from the anthill. “What a lot of rushing around!” he thinks, “On the outside everything is so quiet and peaceful.” And the invisible microbes in his body bustle about their work, bloating him, digesting him, sending him downward, down, down into the earth.

Gogol and Goncharov and Chekhov and the rest of them are fully aware of the appeal of letting yourself go to seed. It’s not all dark and depressing–something in that inertial state allows you to appreciate the fullness of life (though of course there’s always going to be an asterisk for Gogol). And vodka fits in here somewhere. But they are also aware that unless we get up off our butt and go out and build shelter, plow the fields and cook food, we’re not going to have anything to eat, and we will die. So our activeness represents a struggle against the inertial forces of nature, or, dare I say, Thanatos.

Chekhov was a contemplator (he spent a lot of time fishing, for example).

And many of his stories depict people who can’t get anything done. But he was also a doer, and for now let us just mention that he was one of the great gardeners in world literature.

For reverberations, paste this link into your browser:

http://antonchekhovfoundation.org/garden.html

So when the van pulls up to the Letters Museum, I get up off the bench and we (a small delegation from Duke)

head to Chekhov’s house in Melikhovo.

Кonstantin Bobkov, the director of the museum, treats us and Zhenia Bovshik (of the letters museum) to tea, and then we stroll the grounds. “What a lot of rushing around!” we think. During his few years at Melikhovo (1892-98 basically), Chekhov expanded the estate’s pond and stocked it with fish, treated sick peasants, built schools, cultivated medicinal plants, volunteered for the census, wrote great works of literature…

.

.

Having asked about farm animals, with much excitement I learn that there is a stable on the grounds, where people can ride.

This beautiful horse is named Lolita. There are ponies too.

A high point is a visit to the tiny house where Chekhov wrote The Seagull.

If you look up, you will see that an image of this very special place heads up our blog. Let’s call it the Seagull Fleagull (fligel’ being the Russian word for this kind of building). The sign says “My house, where The Seagull was written. Chekhov.” At this point my hand was shaking so much that the photo came out jiggly.

The Fleagull was closed to the public on the day of our visit, but Zhenia had worked her magic and we headed toward the door. On the way we threaded through a bustling family from an unnamed foreign country: mother, father, three small boys, and a grandmother-like person. The family had just learned the building was closed, and was expressing deep anguish, an emotion that spilled over into righteous indignation when they realized our little group was being admitted. Kindness prevailed and we all piled in, filling the little hallway between the house’s two rooms completely. At this point the youngest boy, an adorable (up to that moment) little blond, flopped to the floor and began flailing his arms and legs and shrieking. Recall Pussy Riot in the Christ the Savior Cathedral. A struggle ensued (with the parents) and the sobbing child was escorted out in disgrace. The museum workers remained calm and even smiled indulgently.

And Chekhov’s room filled with silence.

.

.

<3