Deeps > Representing Bois Caïman > Painting Mystery and Memory: Bois Caïman in Visual Art

by Courtney Young

Remembering an event, a person, or a moment in one’s life can be fraught with difficulty. Details shift. Without documentation the exact facts can fade and, at times, take on less importance than the meaning a memory itself has come to represent. It’s this representation of memory that is at the heart of how I’ll be exploring several paintings about Bois Caïman, the vodou ceremony that took place in Saint Domingue (what would become Haiti) the evening before the only successful slave revolt in all of history[i].

An insurrection is, by definition, kept a secret insofar as the whole idea is that no one will discover the plan. Failed insurrections are well documented but only because those who put down the revolts recorded their efforts and tactics. The success of the slave revolt that began that night in 1791 presents its first mystery or challenge (depending on how you look at it) by the very fact that it was successful and, so, was never documented[ii]. Its second mystery/ challenge is that the people who were involved had no means by which to record the event (if they so chose) since they were enslaved and were, consequently, actively and often violently prohibited from reading and writing. This double-whammy of mystery and challenge is part of what makes Bois Caïman so fascinating: It was the beginning of the only successful slave revolt in all of history, and yet no one really knows what happened that night. As Laurent Dubois puts it, “Bois-Caïman remains a symbol of the achievement of the slave insurgents of Saint-Domingue, a symbol not of a specific event whose details we can pin down, but rather of the creative spiritual and political epic that both prompted and emerged from the 1791 insurrection.”[iii]

Painting Bois Caïman isn’t about painting the concrete details of what happened the night of the ceremony since, as noted earlier, that’s not possible. But what it can do it offer a representation of memory; a lens through which to see a moment that’s long gone but resonates still today. It can capture that “creative spiritual and political epic” even if it can’t glean from history’s undocumented moments the minutia of an August night on a Caribbean island in 1791.

The paintings I chose to curate here are far from being a comprehensive list of work on Bois Caïman. Instead, I offer several paintings that present different styles, place emphasis on different subjects or ideas, or, quite simply, had the most information available.[iv] I invite readers to add comments below with notes about favorite paintings and links to where others might view them.

As you proceed to scroll through the paintings keep in mind that all the paintings will include a few key figures:

- A central male figure who is likely Boukman, the houngan (or voudun priest) who led the Bois Caïman ritual.[v]

- A central female figure who is likely Cécile Fatiman who led the sacrifice of the black pig.[vi]

- A black pig said to have been sacrificed during the ceremony and from which the participants drank blood.

- A large mapou tree, under which the ceremony is said to have taken place.

I’ll talk more about those key figures in the paintings and their significance to the painting and the ceremony later, as well as offer some context to Haitian painting.

Artist: Ernest Prophète

The above painting by Ernst Prophète narrates the story and memory of Bois Caïman and places the key figures, mentioned above, in the center of the action. We see Boukman and Fatiman, as well as the black pig, mid-sacrifice front and center, drawing the eye of the viewer to these crucial pieces. The participants form a ring around the central figures, along with natural elements in the work including trees, brush and even the weather. In corroboration with the story of the ceremony, Prophète has painted the scene with stormy clouds across the top of the piece, including lightening bolts zigzagging into the trees. The broken chains held in many if not most of the hands of the enslaved participants (including Boukman) represent the freedom for which they will fight, and the freedom they will eventually secure for themselves and that of future generations. The colors are of note as well. Bright and bold, the pink dominating most of the canvas along with the reds, oranges, and yellows of the participant’s clothing create a sense of distinct visibility, as if the people in this painting are claiming their right to be seen; their right to freedom.

Artist: Dieudonne Cedor Ceremony at the Bois Caïman

In marked contrast to the color palette discussed for the above Prophète painting, the palette in the above Dieudonne Cécor painting is far more muted with the exception of the red attire belonging to whom viewers might assume is Boukman. Literally larger than life, he claims the center of the painting as he does in Prophète’s painting, but this time he towers, at least twice as large, above all other individuals in the scene. Arms raised and gaze upward, he leads the ceremony that will lead, eventually, to an independent nation. In this rendition of Bois Caïman, Boukman is awe-inspiring and commands respect while communicating a sense of serene confidence in the midst of a tumultuous scene full of movement and emotion: Fatiman at his side appears mid dance, her dress swinging as she moves. Those around him kneel, dance, and hold their hands to the sky, drawing the viewer’s eye to the sky – inky black and foreboding, the tops of the trees swaying in a fierce wind. We see the familiar figures of Boukman, Fatiman, and the black pig in the far right. Only this time the lens is much tighter, like the artist has zoomed in on this moment in history, taking us right in to the ceremony where we can feel the heat of the fire. As if we took one more step, we’d enter the circle of the participants, deep within the forest, and join the revolution. Cedor allows viewers to not only remember Bois Caïman, but to be a part of it.

Artist: Nicole Jean-Louis Bwa Kayiman Haiti 1791

Nicole Jean-Louis chooses a wider lens for her painting and, in doing so, draws attention to the action and tone. Viewers can almost feel the stormy wind as it bows the tree in the top left of the painting, or as it whips Boukman’s shirt away from his body as stands, with one arm pointed towards the sky and another pointed forward as if in a charge. Like Cedor’s painting, he is physically larger than the participants in the scene, demonstrating, perhaps, his significance and leadership in the revolution. Since the viewer accesses this moment in time through the rear of the circle of participants, we can see clearly the cross hatch of scars on the backs of many of them left from cruel and violent whippings. As seen in prior paintings and in line with the memory of the event, a black pig lays nearly in the center of the composition, recently sacrificed and blood pouring from its neck. One woman appears to be placing the blood in buckets of cups and another to be walking them to those in the circle. This narrates the part of the memory dictating that not only was a black pig sacrificed, but that participants drank its blood. This ritual will be discussed further in the context of voudo ritual and history. Finally, The sky arches across the entire canvas and we see the horizon almost as if it’s a panorama – curved slightly. The lightening bolts flash across the sky and appear almost like shooting stars. The sky is stormy and threatening. Paired with the prolific distribution of machetes amongst the ceremony participants, almost taking on a shine or glow, the intent of the insurrection is clear: freedom must be achieved.

Artists: David Beaubrun

Interestingly, Beaubrun chooses to focus less on Boukman and Fatiman (in fact, it’s difficult to even be certain of their presence) and, instead, to give the weight of the painting to the tree. He creates this gravitas by dominating the canvas with the image of the tree; it’s branches reaching both towards the sky and to the earth creating, on the left, almost the appearance of prison bars. The more slender roots of the tree appear almost serpent-like, snaking down the trunk of the tree towards the rocky earth. Like Prophète, Beaubrun incorporates a great deal of pink into his work on Bois Caïman. In his piece, however, he uses it primarily as color for clothing as well as some of the environmental details – in parts of the sky and the fire, for instance. The narrative of the night as a stormy one is consistent here again; viewers can see a storm gathering in the distance with lightening cracking across the sky and lighting the clouds.

Painting Style

The style of these paintings could be considered naïve, though the term is misleading as it suggests a sort of naivety or lack of sophistication when, in fact, that’s the farthest thing from the truth. Pierre Appraxine outlines this important distinction when he says, “the best naïve paintings share a special understanding of the world. They express a fundamental belief in the unity of visible and invisible reality…the imagery and symbolism of both modes of reality are integrated into a single visual structure.”[viii] Additionally, he warns, “Above all it would be a serious misconception to consider Haitian naïve paintings as folk art. Folk art generally associated with crafts expresses a collective mind with a minimal individuality of style…naïve art, on the contrary, is above all a personal expression. It may rise out of folk consciousness or return to it.”[ix]

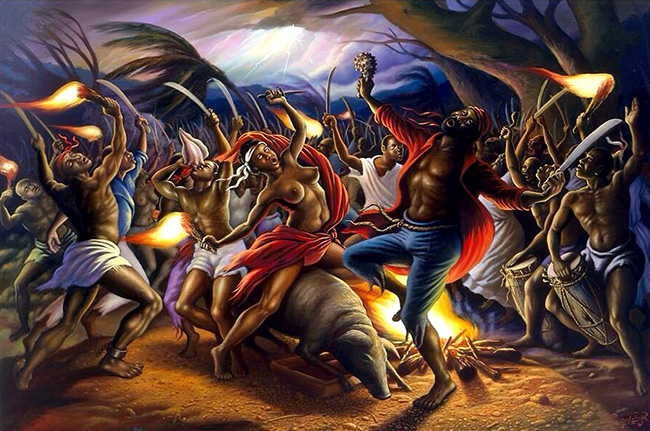

Artist: Ulrick Jean-Pierre Cayman Wood Ceremony

But not all paintings that represent Bois Caïman utilize the naïve style. The painting by Ulrick Jean-Pierre, Cayman Wood Ceremony, demonstrates the use of a realist style, as well as a notable shift in emphasis and narrative.

The narrative we’ve seen in the paintings we’ve seen so far tells a story with Boukman holding significant space in the front of the painting along with the black pig and the mabou tree. We see also Fatiman, though this time she appears to hold much more weight and importance in the event. As Marc Christopher says,

[Jean Pierre’s] interpretation of the event is at once exceptional and innovative in terms of the narrative and the meaning that it conveys…By granting equal centrality to the manbo, Jean-Pierre willingly embraces the revisionist thinking expounded by new research in Haitian history. Indeed, after being downgraded to a supportive role, the personality of Fatiman is being slowly exhumed from history’s oubliettes. Indeed, by rearranging the position and actions of the main characters of the Cayman Wood ceremony, Jean-Pierre has also refigured the narrative to grant a more active role to Fatiman and, by extension, to all the women who participated in Haiti’s war of independence.[x]

This important shift isn’t the only distinction between Jean-Pierre’s work and the work we explored earlier. Christophe describes the work as allegorical, drawing the comparison between Fatiman and Athena, Greek goddess of war.[xi] Undoubtedly there are similarities – both women are situated as brave warriors leading the way into battle. While the comparison is just, I think the parallel to Delacroix’s painting of Lady Liberty, who led the way towards the ideals of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity”, is much stronger. See painting below:

Both women take a dominant stance in the canvas, bare-breasted with their arms raised (Lady Liberty with a French flag and Fatiman with a dagger), both wearing red sashes around their waist that trail behind them given their forward momentum. Additionally, this comparison provides an opportunity for Jean-Pierre to offer a critique and analysis on France’s own revolution fought on the values sought by Lady Liberty – a revolution that led not only France to a republic, but contributed to the rallying cry for the enslaved people of Saint Domingue to fight for their own freedom and their own “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” – something they were categorically denied in the most violent of ways.

Fact, Remembering and Representation

None of these paintings, and arguably no painting about Bois Caïman, capture the facts of the event because no one actually knows them given the reasons discussed earlier. We don’t know, for instance, if Boukman wore red (as in Cedor’s painting) or white (as in Jean-Louis’s or Prophète’s), or if the forest was dense (as in Cedor’s painting) or if there was a clearing (as in Beaubrun’s). But all of the paintings capture a memory that allows the night of August 14, 1791 – and the entire revolution – to reverberate today. Marc Christopher said (in regards to Jean-Pierre’s work) that, Jean-Pierre’s “vision and vivid imagination are capable of giving back to the Haitian people pivotal moments in their country’s history.”[xii] I think, however, that this suggests these critical moments have been stolen by an outside entity or that Haitians have someone lost agency over their own history. Rather than giving back “pivotal moments”, I think all of the painters provide something that is more rooted in their own agency: Remembering an exceptional history that no other people or country has ever been able to replicate, and instead of representing fact (which would be impossible), they represent a story and, in doing so, keep the rallying cry of freedom and equality alive in a world that is still unequal.

You can read additional context about Haitian painting here, or you can read additional information about the aspects of vodou as seen in the above paintings here.

Want to cite this page? Here ya go! Just cut and paste:

Young, Courtney. “Painting Mystery and Memory: Bois Caïman in Visual Art.” The Black Atlantic. Duke University.

[i] When I use the word successful I mean explicitly that the revolt set about to secure freedom for the enslaved people of Saint Domingue and, after thirteen years (1791-1804), they were able to do so. This is not to say that the countless other slave revolts through out history and around the world had less significance or represented a less important resistance.

[ii] Discussion to this end took place in class discussions for The Black Atlantic at Duke University Spring 2014 and also with Dr. Gregson Davis.

[iii] Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2004. Print.

[iv] An interesting side note that arose through my research is that 1) There were fewer paintings about Bois Caïman than I expected, and that 2) There were relatively few articles written about them in English. The information found online about them was sparse and often lacking major details like the artist’s name.

[v] “The Kingdom of This World.” The Kingdom of This World. n.p. 2013. Web. 13 April 2014. https://www.msu.edu/~williss2/carpentier/part2/boiscaiman.html

[vi] Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2004. p. 99-100. Print.

[vii] Cedor, Dieudonne. ArtSTOR. Web.

[viii] Appraxine, Pierre. Haitian Painting: The Naïve Tradition. New York: American Federation of Arts, 1973. pp. 11-12. Print.

[ix] ibid.

[x] Christophe, Marc A. Ulrick Jean-Pierre’s “Cayman Wood Ceremony.” Journal of Haitian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, Bicentennial Issue (Fall 2004), p. 54.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Christophe, Marc A. Ulrick Jean-Pierre’s “Cayman Wood Ceremony.” Journal of Haitian Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, Bicentennial Issue (Fall 2004), p. 52.

Could you supply a jpg of Cecile Fadiman for use in my book, Caribbean Women’s Art, along with permission to publish?

Mary Ellen Snodgrass

5591 Ashley Court

Hickory, NC 28601

828-324-0155

aphra@charter.net

Greetings, I am image researcher for the International African American Museum opening in Charleston, SC in 2022. We would like permission to use in the museum’s permanent exhibition an image of the Painting of Bois Caïman ceremony by Haitian artist Ernst Prophète. Please contact as soon as possible. Thank you for your consideration.