By Andy Cabot

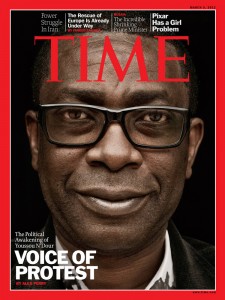

Listening to the song “4-4-44” by Senegalese artist Youssou N’Dour is a mysteriously peculiar experience. The sound and rhythm enters swiftly into your ear, and, at the end, as the distant drums and piano fade out, you realize that your body has quietly turned into a state of near total appeasement. Honestly, only one thought circles into your mind as the song comes to a closing stage: I need to play it again.

What’s so mysterious about that Youssou N’Dour piece? At first, I felt it could perfectly fit in as a fade out song for a Mad Men episode as the credit rolls in and Don Draper meditates on an empty Hawaiian beach about why he has cheated on his wife for the gazillion time this year. After further listening, another picture popped in my head. It felt like this could have been a reinterpretation of a famous popular folk song, or also an adaptation of a child’s song melody. All in all, there was one dominant feeling: this song was a masterpiece of quietness, the quintessence of what peaceful joy and harmony could sound like.

“4-4-44”: N’Dour’s tribute to Senegal’s fortieth year of independence

During the long career of Youssou N’Dour, “4-4-44” is probably an epiphenomenon. His duet “Seven Minutes” with Neneh Cherry and other songs he recorded with his band in the 1990s were more significant in bringing the Senegalese artist to international stardom. At that moment, western media music industries considered N’Dour as the synonym for benevolent feelings of fraternity, loose passion for human rights and more vague sentimental attributes like advocates of world peace trough music. For a long time, it seems like he had his image and personality completely appropriated by the dominant expectations of Western audiences.

Arguably, Youssou N’Dour was not in the best position to develop a radical critique of the West or become an apologist of Afrocentrism when he rose to fame in the late 1980s. Indeed, he never felt any hatred or extreme passion neither towards Africa nor towards either of the two dominant ideological camps of the Cold war era during his early musical career. N’Dour was a quite discreet character, far from the strong political opinions and eccentricities of other Afro-artists of the same era like Fela Kuti. His politics were almost void, still, his musical interests were immense.

Interestingly, retracing N’Dour’s crooked musical path leads us almost inevitably to interrogate his country’s history. For centuries, the present-day territory of Senegal had been nurtured and shaped by the movements and intersections of different civilizations. Even before the Ghana and Mali empires rose to continental preeminence around the fifteenth century, the major linguistic groups who now constitutes the Senegalese community –Wolof, Serer, Lebu, Tukolor, Mandinka, Diola- had already established strong commercial relations with the Abbasid Caliphates. By the 11th century, these groups were thus already fully integrated to the circuits of trade, knowledge and diplomacy of the Transaharian world economy. Contacts with European kingdoms erupted later on and were mainly directed at improving the plantation economies of Euro-American colonies. Indeed, despite intense resistance on the part of different linguistic groups, the great majority of Senegambia kingdoms were turned into large-scale suppliers of African slaves in the 18th century. The demographic and cultural legacies of the slaves-trade are still largely observable nowadays. All in all, at the beginning of the 20th century, one can see the modern Senegalese state as shaped over centuries of intercontinental and inter-religious relations. The salience of these multifarious cultural influences was decisive in creating one among the most vibrant musical traditions of West Africa.

“Senegal’s geography has brought its people into close contact with North Africa and the West and made Senegal a crossroads where Black African, Islamic, and European civilizations have met, clashed, and [1] blended”. Though this statement might appear un-original to many regards, its importance does not singly lie in the significance of the historical identity the author seeks to demonstrate but also in its relevancy if considered under a musical perspective. Indeed, Youssou N’Dour came to music as History came to Senegal: by the passage of caravans. In the late 1980s, while his family held doubts about his musical potential, N’Dour relied on the financial aid of the French-Senegalese community to launch his career. In 1983, Senegalese cab drivers working in Paris helped him raising funds so he could produce his first title. The latter was released shortly after the fund raising campaign and became an instant hit in France. Its title was “Immigrants” and certainly left no doubt about the intentions of N’Dour who sought to express his gratitude and support to migrants all over the world and especially to Senegalese ones.

At the turn of the decade, N’Dour had achieved a near status of world-music icon. Similarly to Alpha Blondy or Fela Kuti, his Afro-rhythm pop was now commercially successful not only in Senegal and Europe but also in North America. He had recorded songs and toured with Peter Gabriel, Sting, Bruce Springsteen and Tracy Chapman while being held as a proud symbol of success in his native land. Still, by the mid-1990s, his commercial success declined along with financial funds from North American record companies. The artist was not too surprised by that situation. Surely, he felt disheartened by the neo-imperial logics that controlled and influenced the relation between world markets and access to music. To illustrate that idea, N’Dour did declare after the release of his LP Wommat (The Guide) in 1994 “It’s a matter of pride for me to have produced this album from A to Z in my own studio”[2] .

Shaped by various cultures ethnically divided by colonialism, Senegal and N’Dour entered the post-1991 world in a state of indecision about their destinies. In 1980, its leader Léopold Senghar Senghor- educated in the French métropole in the 1930s and strong advocate of pro-French views in foreign and domestic policies during his twenty years long presidency between 1960 and 1980- left the country in a state of strong democratic stability while domestic oppositions vilified its “reign” as favorable to neo-colonial nepotism and discriminatory against Muslim and traditional communities. During the subsequent decades, this divide between pro-French elites centered on Dakar and other demographically dominant communities in Senegal would not cease. By the end of the Cold War, Senegalese people recognized that distance from the Atlantic powers –especially France- would revitalize the country’s culture and economic dynamism.

The song “Immigrés” was a turning in point in that larger process. For N’Dour, it represented an early effort at creating music blending eclectic influences for Western audiences. The piece associated different styles of drumming and rhythms forged into Western African culture mixed with various musical tempos from Latin America (Tango), North America (Jazz) and the Caribbean (Reggae). Known as mbalax, this genre would later being largely identified with Youssou N’Dour, whom while not inventing it transformed it into an extremely popular music in West Africa.

For a long time, this almost unavoidable association of Mbalax with N’Dour went unnoticed even by the artist. By the 1990s however, as the country’s faced economic difficulties and many of its African neighbors descended into full fledged civil wars, discontents towards this association emerged. As explained earlier, though N’Dour expressed few political stances while he experienced international fame, the backslash of the Western industry against its more traditional orientation in the late 1990s had left him disheartened. Within the space of a decade, N’Dour and Senegal once again followed an intimately related path. Faced with economic pressures from the West and internal pressures from inside, a certain return to tradition accompanied by a slight De-Westernization of the elites occurred.

Concerning N’Dour, this process achieved its maturity in 2004 when he released his album Rokku Mi Rokka. It came into the form of “4-4-44”. During the first part of the song, N’Dour proposes a blending of the joyful and celebration-like Mbalax sound that made him famous. Still, midway through the song, this rather fragile pop aesthetic turns into a denser atmosphere. As a son of a griot– central figure of Western African traditional societies transmitting communities history and legacy through songs and stories- N’Dour always remained close to the ancestral music of Muslim and animist communities of Senegambia. In “4-4-44”, this feeling of tradition is present in the most manifest way. Indeed, as the initial upbeat structure progressively fades when the song enters its second part, the Western ego of N’Dour relinquishes and its African self reappears as xalam strings make their way into the harmony.

Short video documentary on the tradition and influence of Xalam in West Africa

Music scholar Ronald Radano once argued that Black music in the US shared a strong sense of remembrance borne “directly out of the depths of social tragedy only to rise up miraculously in the voice of racial uplift”. In a recent article, Laurent Dubois attempted to go beyond this type of analysis centered on the Anglophone Atlantic by arguing that, by expanding the chronological and geographical frames of the Black Atlantic, one could easily seize the broader historical implications of Black music “Some songs also offer broader historical narratives, tracing the History of Haiti’s population from Africa through struggles in the new world”. Largely, Dubois’s analysis tends not to decenter the traditional questions of Black music scholars but rather to connect the often forgotten parts of the Black Atlantic to the dominant black Anglophone world. Indeed, while he focuses on traditional Vodou songs in 18th century Haiti, Dubois emphasizes on the contained metaphors and images evoking the slave-trade in the creole culture : “But that layers onto another set of symbols: the Atlantic ocean as giant graveyard for those lost on the Middle passage, as a site of ancestral death and memory. In this song, though, an origin in the depths of the water doesn’t preclude a soaring present, [3] uncaptured”.

As I would argue here, N’Dour cannot be easily connects to “traditional” themes of the Black Atlantic: loss, displacement and painful remembrance. Indeed, as Saidiya Hartman beautifully explained in her book Lose Your Mother, though it is possible to draw an emotional connection between the African diaspora and African people, recent years have shown the historical gap increasing between the two continents in their relations to the slave-trade and its legacy. When the author retraces her journey through different iconic locations of slave-trade history in Ghana, she insists on the impossibility for native Africans to feel to what extent the wound of displacement is deep for those who were captured and deported “Love longed for an object, but the slaves were gone. In the dungeon, missing the dead was as close to them as I would come. And all that stood between artifice and oblivion was the muck on the [4] floor”. N’Dour explicitly tackles that issue in “4-4-44”. As first and foremost a tribute to Senegal’s fortieth year of independence achieved on April 4th, 2004, one can perceive N’Dour words as expressing a distinct –perhaps even new- feature of the modern Black Atlantic: namely the notion of a purely prideful remembrance of the Black past not rooted in the history of a “social drama” but rather in the mental overcoming of that trauma.

During his early musical career, N’Dour often took his distance with politics. In January 2012, while still recording albums and touring West Africa, he decided to present a bid for the coming Senegal’s presidential election. One of his first statement as a candidate epitomized N’Dour and Senegal’s intertwined historical fate “C’est vrai, je n’ai pas fait d’études supérieures, mais la présidence est une fonction et non un métier. J’ai fait preuve de compétence, d’engagement, de rigueur et d’efficience à maintes reprises. A l’école du monde, j’ai appris, j’ai beaucoup appris. Le voyage instruit autant que les livres »[5] (I admit it, I have not attended higher education, but the presidency is a duty and not a job. I have proved that I’m skilled, that I’m hardworking and rigorous on many occasions. The world has been my classroom, and he taught me a lot, so many things. Traveling teaches you as much as books). The artist did not won the election and that was no surprise, it was a detail. As he contemplated his past experiences in relation to those of his country, N’Dour once again proved how personal histories can change you and thus History can be change if you stay faithful to your past. In Senegal as in other West African countries, N’Dour knew perfectly how to achieve just that: by not missing the next caravan.

[1]Gellar Sheldom, Senegal: An African Nation between Islam and the West, Westview Press, 1982.

[2]Frank Tenaille, Music is the Weapon of the Future: Fifty Years of African popular music, Lawrence Hill books, 2002, 232.

[3]Dubois Laurent, Afro-Atlantic Music as Archive, 2013, [Online],Available <http://sites.duke.edu/banjology/> [Accessed: 19 April 2014 , 15.]

[4]Hartman Saidiya, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, Farra Strauss, 2007, 135.

[5]Aude Lasjaunias, Youssou N’Dour croit en son étoile présidentielle, January 2012, [Online], Available <http://www.parismatch.com/Actu/International/Le-chanteur-Youssou-N-Dour-candidat-a-la-presidentielle-senegalaise-147294>, [Accessed: 19 April 2014].