By Andy Cabot

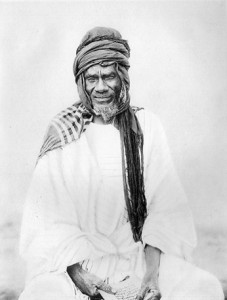

In 1867, the Malian warlord Samory Touré engaged a decision that shaped his country’s destiny. Three years before, the Toucouleur’s Emperor El Hadj Umar had deceased and consequently left his territory at the mercy of European powers in the region. In order to preserve its integrity, options were few. Indeed, after years of costly military resistance to French and British armies, the different kingdoms and tribes from the Mali region had almost abandoned all hopes to retain their independence.

After some hesitations, some Malian lords decided that the fight should continue. Samory Touré considered leading this new effort against European encroachments in the Niger valley as his duty. He had historical precedents to rely upon. Among them were Sonni Ali Ber –the Sudanese born military genius who had vanquished all his enemies in the fifteenth century to take control of the legendary city of Tombouctou- and El Hadj Umar – founder of the Toucouleur Empire who defeated the French and Bambara during the 1850s Niger wars. Despite their obvious military talents, Umar and Sonni Ali had achieved their epic ambitions due to a simple reason: conversion to Islam , or the sole spiritual and cultural force capable of founding unity between African and Muslim kingdoms to resist European colonization in the 19th century.

So, in 1867, Samory Touré –as his glorious predecessors- made a decision that, once again, changed the nature of military resistance against European countries: he converted to Islam. Such a gesture might appear innocent and devoid of any ideological motives. On the contrary, it meant everything. During the 19th century, as West African kingdoms faced military and political submission by France and Great-Britain, cultural and ethnic unity was the crucial test to overcome for the diverse linguistic groups inhabiting the Niger valley region. Thanks to highly symbolic political decisions as those of Samori Touré, this objective was temporarily achieved and resistance went on successfully in the following decades. Touré eventually died in a French colonial prison located in the Gabon colony in 1900 after suffering from military defeat and capture during one of his final act of defiance. Clearly, as he approached the dawn of his life, Samori’s conversion in 1867 did not mean much anymore. By 1900, nearly all of West Africa as well as Sub-Saharan Africa had been colonized by European nations – thus marking the failure of a transcultural resistance unifying Muslim and African kingdoms together against the West. As the century and Touré came to a simultaneous end, African resistance entered a period of silence. [1]

Through spiritual and ethnic unity, Samory Touré and past Malian kings defended their cultural heritage in a period of colonization. In the late 20th century, their late descendants chose a different approach. In 1960, while Mali and other French colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa acquired their independence, the métropole was faced with great economic and diplomatic challenges. As world politics were then intensely polarized on the large scale military and ideological opposition between the United States and Soviet Russia, former colonial powers as France and Great-Britain relied on their vast empires to acquire vital natural resources (oil, uranium) and thus develop their foreign trade. By the early 1960s, as anti-colonial movements were gaining ground in certain colonies (Algeria, Kenya), France and Great-Britain were forced to grant independence to their African colonies. What would be the legacy of that decision? Would African states develop and rise to the international stage? Were France and Great-Britain really “leaving” the continent in control of its historical destinies?

In September 2012, while sitting on a typical Parisian coffee terrace, the rapper Oxmo Puccino was waiting for an interviewer from Libération –one of the three leading national newspapers in metropolitan France. During the middle of the interview, he stated “Je pense que personne ne peut expliquer les rapports avec sa terre en quelques mots, en quelques lignes. Ca prend toute une vie” (I think no one can understand the bond one has with his homeland in a few words. It’s the work of a lifetime)[2]. These emotional bounds evoked by Puccino were those of a young Malian forced to leave his homeland in 1976 with his family to find a better life in the distant French métropole, the former colonial ruler. Indeed, his mother –a nurse and housewife- and father- a locksmith- had both their destinies intertwined with that of French neo-colonial policies conducted in the aftermath of decolonization.

For many French of Malian and Antillean origins, strange acronyms such as BUMIDOM and AFTAM represented a decisive moment of their personal histories. These organizations known as Bureau Pour le Développement des Migrations d’Outre-Mer and Association pour l’Accueil des Travailleurs Africains et Malgaches were created to enroll cheap Antillean and African workforce in low skilled and badly paid activities in major French cities like Paris and Lyon during the 1960s. In 1963, the newspaper Le Monde reported that labor conditions for this newly “black” workforce was a near synonym of “esclavage volontaire” (indentured servitude) [3].

When Abdoulaye Diarra saw the light of day in 1975, his future destiny as a leading artist of the Francophone rap scene started on a rather fragile ground. His Malian parents were part of the great mass of African migrants from the post-independence years who worked in low-paying jobs and made just enough to raise a family. During his adolescence, artistic prospects still looked dim as Abdoulaye eventually dropped out of high school during his senior year while still managing to successfully pass the precious Baccalauréat –the high school graduation exam in France- and make it to college as a literature major.

In the 1990s, rap became a very popular genre in France. The French scene was mostly then composed of artists born of Algerian, Tunisian, Malian and Antillean parents. This second generation of French black migrants shaped the particular sound and themes of the Francophone rap scene. Considered as the “golden age” of French rap, the 1990s and early 21th century saw legendary groups and artist-IAM, NTM, MC Solaar, Assassin, Kery James, Lunatic, Ministère Amer, Doc Gyneco- emerging as bestselling acts in the Francophone and European music industry. As this era came to its dawn, Abdoulaye Diarra acted as his distant ancestor Samory Touré a century and a half before him. He transformed himself. He became Oxmo Puccino.

From Diarra to Puccino, one can easily recognize the cultural gap between Touré’s conversion to Islam and the French rapper’s decision to change his name. In the late 20th century postcolonial world, dynamics of resistance had evolved for the young French-African migrants. There was not military conquest at stake, but a mental one. As means of explanation, the nowadays more mature Puccino delivers a sensible argument for this identity twist: a transatlantic passion, that of Italian-American gangster movies, especially The Godfather saga “Ces films m’ont marqué parce que c’est une fresque familiale. L’histoire d’un immigré qui s’installe dans un pays gigantesque ou on parle une autre langue et qui se retrouve dans un milieu où il doit élever ses enfants, gérer son héritage et s’en sortir. On y comprend l’importance de la famille, du travail, du respect. Toutes ces choses qui font de toi un homme.” (These movies touched me because they dealth with family. The story of a young migrant who settles in a huge country where people speak a foreign language and finds himself in an environment where he must raise his children, manage his money and make it. One understands the importance of family, work, and respect. All these things that make you a man.)

In many regards, Puccino was asserting a sort of broader consciousness not limited to French-African migrants at the time. In the 1990s, after a decade of hesitations and vagrancy, Francophone rappers started to develop their own themes and sounds to tackle the societal issues they were encountering: racial profiling, the failures of national assimilation, but also the emergence of a new sense of community. Indeed, as many French rappers of this era grew to the sound of classic US funk and hip-hop music, feelings of admiration and discomfort grasped this generation. For American rappers such as Public Enemy or Cypress Hill, the idea of blackness was far from being a distant legacy of colonialism transported to another continent, but rather a very sizable fact. As French Africans matured their sound and musical techniques listening to American hip-hop, the “black” communities in US rap still seemed far more visible and present than in the French.

In the end, as a consequence of language and cultural distance, few French rappers turned into a full appropriation of community discourses. On the contrary, for the great majority, the French language and musical traditions were far more pronounced than American ones. In the case of Oxmo Puccino, this situation took on very concrete dimensions. As he is sometimes celebrated by French media as the black Jacques Brel due to his late return to a more jazzy-slam like kind of sound, Puccino might be considered as a precursor for many young rappers of the generation that followed the “Golden Age”. Names like Abd-Al Malik, La Rumeur, Grand Corps Malade or Dooz Kawa cite him as a decisive influence for elaborating their touchstone jazz rap sound in the early 21st century.

After a few semesters in college and some early musical efforts, the fate of Puccino appeared clearer. Throughout his years of formation, his curiosity made him travel from Francis Ford Coppola to Sly and the Family Stone and back to Serge Gainsbourg and Jacques Brel. In 1998, at age 23, he was ready to assert his new self: that of a transnational, globalized Black wishing to surpass the neo-colonial pressures of French society. Such a trajectory might bear little resemblance to that of Samori Touré. Indeed, in the 1990s, though suffering from overall poor social and cultural conditions in France, people of Malian origins were not facing civilizational extinction by foreign armies. They were past these times of unilateral subjection through direct violence and plundering. Puccino was no Samori Touré, though some of his acts certainly echoed to the great Malian resistant.

In his first two albums –namely Opéra Puccino and L’Amour est Mort (Love is Dead) respectively released in 1998 and 2001- Puccino positioned himself as a resistant. What was he resisting against? He was denouncing the impossibility for “Blacks” to be recognized as a specific community in France. During Puccino’s childhood, social conditions and questions of identity had evolved for second generation French-Africans. Through a landmark analysis by Rémy Benzaggua [4] , we can delineate three phases in the construction of a specific black identity in France: First, between 1960 and the early 1980s, African and Antillean considered themselves as part of a similar blackness because of their equally poor social conditions. Second, in the 1980s and 1990s, this unity fell apart when Antillean migrants began to outnumber Africans, and received better positions as civil servants in the national health services, education, and local administrations. Antillean migrants started to distance themselves from African. Third, at the turn of the century, the growing mass of second and now third generation migrants recreated a firmer sense of shared blackness by attending the same elementary and middle schools and often attaining college education. One among the numerous factors for this “renaissance” of blackness is to be found in the emergence of rap and hip-hop as a fundamental vector of blackness.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSYRDMwESRs

The song “Ghettos du Monde” (World Ghettos) released in Puccino’s second Album L’Amour est Mort embodies this new black hybridity built through music by second generation migrants. A hybridity caught in between the greater access and interest to worldwide music -specifically Anglophone rap- and the attachment to their double traditions: African and French. In many ways, “Ghettos du Monde” is first and foremost a humble call to consciousness for Puccino’s generation. Aware that their parents suffered from far worse social conditions than them, the artists reminds us of this historical legacy which constitutes a bound between these generations. On the first verse, he claims that those who lived in the ghettos are “Des gens biens sous des sales masques […]” (Respectable people under dirty masks). Here, once could draw a parallel with Frantz Fanon’s analysis of the process of cultural hierarchy inflicted upon African and Creole migrants traveling to the metropole during the late colonial era. For Fanon, an African or Antillean’s first encounter with the “real” France in the 1950s was often met with disappointment and regret when one had to return to to his homeland and realized the almost psychological brainwash he had suffered from “He leaves for the pier and the amputation of his being diminishes as the silhouette of his ship grows clearer” [5].

Though he might refer to some types of racial defense mechanism in this passage, Puccino then claims that stigmas shall not blind us from our direct past, especially those of 1st generation black migrants in France whom Puccino’s parent belonged to “Ghettos du monde. Lève ta main et respecte. Pour ta mère et ton père du bled” (World Ghettos. Raise your hand and respect. For your mother and father from the garbage land). Clearly, here, Puccino insists on the profound dichotomy between his parents born in the “bled” (the garbage land) and people of his generation born in France. Despite the rallying cry features of his song, the artist has no ambiguities about the future he envisions for his generation: be an integral part of French society while retaining their attachments to their homeland and their new transcendental “blackness”.

In her book Lose your Mother, the Afro-American author Saidiya Hartman provides a well-thought out approach to describe this recurrent appeal to the Afro myths of “Mother Africa” and the slave-trade legacy in the 21st century. As she meditates on the 1960s Pan-African movement in the US, her reflection tends towards a sentimental apprehension on the failures of these movements and the still latent legacy of racism on both sides of the Atlantic:

I envied them. In the sixties it was still possible to believe that the past could be left behind because it appeared as though the future, finally, had arrived; whereas in my age the impress of racism and colonialism seemed nearly indestructible. Mine was not an age of romance. The Eden of Ghana was nearly had vanished long before I ever arrived [6]

Here, Hartman tries to explain why a loss of illusion rather than a continuing hope is at the core of contemporary references to the slave-trade, segregation, and racism in Atlantic societies. While Puccino and other Afro-Atlantics could claim a genuine passion and sincerity for their African roots, Hartman reminds us that the social and cultural conditions for these kinds of discourses have been profoundly altered since the 1960s. Ultimately, there could be multiple answers to these questions. The fact that globalization drastically transformed cultural and ethnic affiliations for different categories of population -especially those with migrant roots in Western countries- can shed light on Oxmo’s reference to the Atlantic horizon, and they must be constantly regarded within this larger context. Also, this literary attempt to mobilize the slave-trade for purposes of ethnic solidarity demonstrates to what extent tactics of resistance have changed within the space of one century for black populations in Africa and Europe. Still, throughout different time and space, as locations and contexts escapes linear logics, Samori Touré’s conversion, and Oxmo Puccino’s modern anthem relates to a common ideal of the Black Atlantic: the necessity of identity in times of doubt, loss, and defeatism.

[1]A summary of Samory Touré’s resistance is best rendered in: N’Diaye Tidiane, Mémoire d’Errance, Paris, Harmattan, 1998.

[2]Laireche Rachid “Oxmo Puccino. Griot du rap”, Libération 14 September 2012, Libération.fr, 4 April 2012.

[3]Blanchard Pascal, Deroo Eric, Manceron Gilles, Le Paris Noir, Paris, Editions Hazan, 2001. 158.

[4]Bazenguissa-Ganga Rémy, “Paint it “Black” : How Africans and Afro-Caribbeans became Black in France” in Danielle Keaton Trica, Sharpley-Writing T.Denea and Stovall Tyler, Black France / France Noire: The History and Politics of Blackness, Duke University Press, 2012, 145-173.

[5]Fanon Frantz, Black Skins, White Masks, New York, Grove Press, 1991 (original date of publication: 1967), 26.

[6]Hartman Saidiya, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, New York, Farrar

Strauss and Giroux, 2007, 38.