By Courtney Young

Leyla McCalla writes an album that’s a tribute to Langston Hughes, it’s true. But what she also does is ties the listener through Hughes to the Harlem Renaissance, to his prolific writing about race relations in the US and, ultimately, to Haiti and its slave revolt, the only successful slave revolt in history.

It’s a deft slight of hand, but McCalla passes the listener through time effortlessly, carried on her swinging, warm voice and the strings of her cello plucked more like those of a guitar or mandolin. In this way she connects the dots between contemporary New Orleans (the place she calls home), Harlem in the 1920’s, and Haiti (or Saint Domingue) in the 1790’s and early 1800’s. It’s no small feat. But in this feat she distills to the surface not only the traumatic experiences of slavery and racism in the US and around the world, but connects the listener to its omnipresence – to the reality that while slavery in its colonial form in the US and the Caribbean colonies might be over, it is still very much present. In other words, the Haitian revolution took place over 200 years ago, but it’s consequences and traces echoe through history in Langston Hughes, his poetry, and his writing, and reach us today through Leyla McCalla’s vibrant music. With McCalla’s beautiful album, she connects the past to the present noting that even if something is technically past, it’s still very much present, and something that must be addressed.

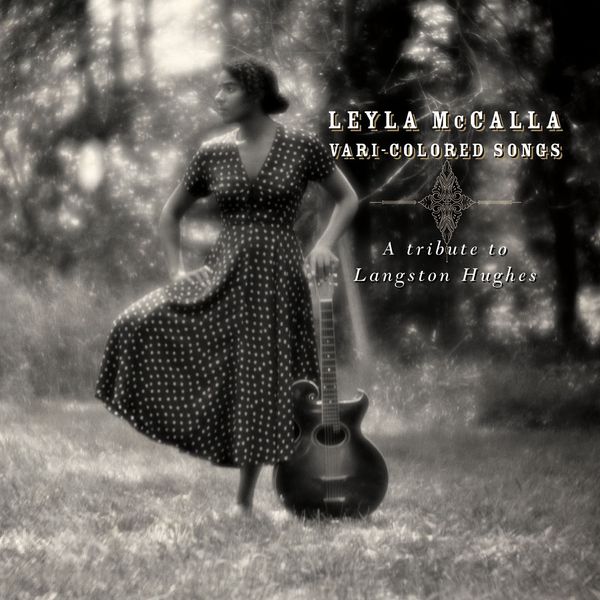

The album, ‘Vari-Colored Songs’ takes the title itself from one of Hughes’ poems and most of the songs take their lyrics from his poetry with a handful of traditional Haitian folktunes interspersed.

The songs deriving their lyrics from Hughes poems make the connection for the listener to the Harlem Renaissance and his entire body of work while the folktunes connect the listener more directly with Haiti, its culture, history, and story. The opening song, ‘Heart of Gold’, with its lyrics pulled from the poem ‘Vari-Colored Songs’ itself, frame the whole album and tip the listener off to where it is that she’s going with the entire work. McCalla says, “The words have always felt to me like a view into the mind of Langston Hughes — a glimpse of the life experiences, colors, and themes that run throughout his immense body of work.” (“American Songwriter”). The poem (and lyrics) follow (click image below to see video):

If I had a heart of gold,

As have some folks I know,

I’d up and sell my heart of gold

And head north with the dough.

But I don’t have a heart of gold.

My heart’s not even lead.

It’s made of plain old Georgia clay.

That’s why my heart is red.

I wonder why red clay’s so red

And Georgia sky’s so blue.

I wonder why its’ yes to me,

But yes sir, sir, to you.

I wonder why the sky so blue

And why the clay’s so red.

Why down south is always down,

And never up instead.

Through Hughes’ poetry and her own music, McCalla speaks to themes (as she says herself) that run through not only America’s past but also it’s present. The lyrics (poem) themselves are mournful, yearning to “sail my heart of gold and head north” away from the virulent racism, trauma and violence plaguing the American South (though certainly not exclusive to it). There’s a significant sense of wonder (it’s repeated three times) and questioning about the world and why it is the way that it is. Wondering why the clay is red and the sky is blue mirrors the senselessness (yet stark reality) of why for some (white) people a ‘sir’ is required in greeting but for others (black) it’s not. Hughes toys with the meaning of ‘down’ and ‘up’ alluding to its obvious geographical context (the South being literally down) but also to its emotional state being ‘down’ or otherwise sad, depressed, or low, reflecting Hughes’ experience of the South. An experience undoubtedly resonant with others during his lifetime as well as before him and still after him. That’s a powerful entry into an album. Before we even make it to song two, the listener has been connected to the powerful themes of the Harlem Renaissance and the stark reality of racism in the United States. But in truth even more has happened if we care to dig a little deeper.

Langston Hughes is an interesting choice for McCalla not only because she provides a platform through her music for his poetry and the messages but also because of the strong connections he himself had to Haiti, the land of McCalla’s own ancestry. He traveled to Haiti in 1931 along with friend and artist Zell Ingram (Black American Literature Forum, vol. 15 #3). They drove through Florida and then made the remaining trip by boat via Cuba. For two months they relaxed in anonymity and only on the last day did Hughes put on a coat and tie and visit Jacques Roumain, leading writer and thinker born to an affluent, mixed-race family and raised in Haiti (ibid).

It seems these two legendary individuals struck up an immediate friendship that would last until Roumain’s early death at 37 (ibid). This connection to Haiti would last through Hughes’ own lifetime and, over the course of it, would include a body of work that included not only poetry but also memoirs of his journey including I Wonder as I Wander in which he comes to understand, in his own words, that, “It was in Haiti that I first realized how class lines may cut across color lines within a race, and how dark people of the same nationality may scorn those below them.” (ibid) His interest in Haiti compelled him, additionally, to pen a play (that would become the opera, Troubled Island) about the Haitian Revolution (wikipedia). Following this path through Hughes’ writing, life, and interests, it becomes clear that artist and musician Leyla McCalla has invited her listeners not only to hear an album of incredible music, but also to walk through (and think through) international issues of race and racism, classism, the African Diaspora, and how moments of the past (like the Haitian Revolution) resonate throughout history and are omnipresent. We see the past as omnipresent clearly below as Langston Hughes grieves in the poem (an excerpt) written in response to his friend, Jacques Roumain’s, death.

You’ve gone

But you are still here.

From the point of my pen in New York

To the toes of the blackest peasant

In the morne [hill]

Always

You will be

Man

Finding out about

The ever bigger world

Before him.

Always you will be

Hand that links

Erzulie to the Pope

Damballa to Lenin,

Haiti to the universe

Bread and fish

To the fisherman

To man

To me….

(Black American Literature Forum)

Like Jacques, and now like Hughes himself, the Haitian Revolution is technically gone, but in fact it’s very much still here. It lives in the lyricism and message of the poems of Langston Hughes, and vibrates today through the music of Leyla McCalla whose own history resides in Haiti even as she plucks the strings of her cello in the present. The past is, as Hughes repeats, not actually past. It’s “still here”. It’s always. As McCalla says herself, “The racism that we experience today is not as plain to see as it was before but it still exists. A lot of what I’m trying to figure out through my work is trying to understand why it still exists and how to deal with it” (rfi english). That’s a lot to accomplish in a debut album, but McCall handles it effortlessly, and leaves the listener not only thinking, but humming along.

You can listen to McCalla’s compelling and vibrant album on her website (watch out, it may leave you wanting to kick up your heels in the streets of New Orleans) or click here to purchase it.