|

|

Of all my weird interests in life, the one that has gotten the most out of control is definitely my obsession with plants. After purchasing my first succulent plant (corpuscularia lehmanii) for $1.99 at CVS my senior year of high school, I became fascinated with desert plants and their resilience. Since then, I’ve acquired about 50 different plants, and have swiftly run out of room for them all, hanging them in shower caddies on my dorm room wall and leaving nearly half of them with my grandmother while I am at school in the winter. Naturally, I was beyond excited to see so many beautiful plants in Morocco. Of course, I was immediately struck by the many cacti and succulent plants, but also have come to appreciate all the other abundant plant life in Morocco.

Plants are extremely common in living spaces in Morocco. The exteriors of buildings are often unassuming but are lavishly decorated within. Some buildings, namely riads, or large houses, have courtyard gardens, often filled with fruit trees or other plant life. These usually surround a fountain in the center of the courtyard. Below is a photo of the Alif Riad, a space for students to study and meet for clubs. Rooms with study space and other purposes surround the courtyard.

The Alif Riad courtyard

Similarly, the school where we take our classes hosts a large and lush garden space where students spend most of their time outside of class. It is clear that including plant life into living and working spaces is an important aspect in Moroccan culture.

The ALC/Alif garden While some of these plants are native to their current homes, others have traveled far to call their current gardens home. For example, when staying at a riad in Meknes, I noticed an aeonium plant, a small genus native only to the Canary Islands, Madeira Islands, and small portions of East Africa. Like the plants I had brought into my home, this plant was not native to the area but was sought after for its decorative beauty (however, unlike my plants in Virginia, this one was thriving in the Moroccan climate).

An aeonium plant in a riad in Meknes Beyond the cultivated gardens in the city of Fez, we were also fortunate enough to see the diverse plant life along the roads of Morocco on our many road trips across the country. Along the way to Chefchaouen, Meknes, and the Sahara Desert, we passed through dense forests, agricultural fields, abundant desert agaves, and stretches of land with no plants to be seen.

The different types of plants reflected the diverse conditions throughout Morocco and I enjoyed the opportunity to witness all the different landscapes in the country. Often when people (myself included) imagine North Africa, images of large trees and rolling fields are not those that come to mind. Viewing Morocco’s plant life as we traveled throughout the country has been a reminder of the different aspects of this beautiful country.

Moroccan forest seen on the drive to the Sahara Desert  Crop fields in Morocco When driving to Chefchaouen, we passed rows upon rows of trees, perhaps argan or olive, as well as other crops like wheat and sunflowers. These called to mind all of the products that I had seen on the streets of Fes Medina, such as bottles of argan oil, arrays of

spices, and fresh fruits and vegetables.

One of my biggest goals for my plants at home has been to get them to flower, something that they haven’t done yet given their conditions being quite different than their native environment. This is certainly no problem for the succulents in Morocco, and we passed hundreds of giant agave plants with flower stalks towering overhead.

Large agave plants with tall flower stalks The most striking moment of all was when we reached our final hotel stop before journeying to the Sahara Desert. My friends and I had ventured out to stand by the hotel gate and gaze at the rolling sand dunes ahead of us when I noticed a beautiful bush of small succulent plants. We were in the middle of nowhere, only a few hundred meters away from the sand of the Sahara, in 110 degree weather, and somehow the plant’s small leaves remained full of water so that it could thrive in a place that our group could barely stand for a few hours. Soon afterwards, after an hour and a half on camels, not having seen a large plant for miles and miles, we came to the Sahara camp where we spent the night and were surprised to find it framed by huge trees.

Desert succulent near the Sahara

The Sahara camp and surrounding trees

Although on this trip we’ve seen so many different and beautiful aspects of Morocco- architecture, history, animals, landforms- these plants all stuck out to me as reminders of Morocco’s varied industries, landscapes, and traditions and the beauty in each of them.

Coming to Morocco, I knew that I would be learning a lot about the idea of citizenship – both national and global – and how it plays a different role in different places based on distinctions between societies. Citizenship for the average American, for example, is not the same as citizenship for the average Moroccan, but there are clear similarities between the two as well (not to mention different definitions of citizenship across individual people). I’ve been talking to several Moroccans about their thoughts on these concepts as well as life in Morocco. I had the chance to interview a very interesting person recently, Halima. She cares a lot about education; she just got a master’s degree in cultural studies, but she currently works as an English teacher. Below is a transcript of our conversation.

The pizza Halima ate during our interview

ME: Halima, if you got your degree in cultural studies, why do you want to teach English?

HALIMA: I love talking to new people, foreigners, discovering new culture. So how am I going to do it? I chose English. And once you’re done studying a language, that’s all you do. Teach that language, and then you go explore. But my real dream is to work for an NGO. I love helping people, and part of teaching is helping people, but that’s definitely what you do with an NGO. In human rights NGOs and women’s rights NGOs, you help people change their situation and also experience new culture, so that is what I really want to do. But it’s not that easy to do that in Morocco.

ME: What is not easy about working for NGOs in Morocco?

HALIMA: Normally they are not very well-organized, and even if they are, the salaries are not very good, so that’s why my goal is to work for a big NGO abroad. I also want to study outside of Morocco to further my English education because the universities are not very good. I did a master’s degree here, and I don’t think I grew in my knowledge. I want to go get another master’s or maybe another doctorate and actually grow; I want to go somewhere like America where I can learn, and people want me to grow and are actually proud of my success and education.

ME: After your studies, would you want to come back to Morocco or stay in America?

HALIMA: If I get a good job with a big NGO, I would stay there. But I would really like to start my own NGO here, I just don’t want to live here forever. If possible, I’d set it up in Morocco but run it from America. I am really drawn to American culture, but more importantly, I also feel uncomfortable sometimes in Morocco. I used to wear the hijab, but I don’t anymore, and there are traditions I don’t follow. I don’t want to feel like I have to hide myself from my family or others and not be myself. At the same time, there’s a lot of judgment – like on Facebook, I’ve deleted so many “friends” over this – and no one should deal with that. It’s very uncomfortable and I feel judged constantly for my decision.

ME: And this judgment is because you don’t follow traditions of Islam, correct?

HALIMA: Well, actually, the traditions don’t necessarily have anything to do with Islam. Some do, yes, but for the most part traditions are just created and imposed by society. For example, while the Quran does mention the hijab, it is those that run society that chose to interpret the Quran a certain way and force women to wear it. Many traditions were created by men just so they could find a way to control women.

ME: In that case, what does it mean for you to be a woman in Morocco?

HALIMA: To be a woman here, you have to choose one of three paths. Either there is the path where you can just submit to whatever society tells you to do, whatever traditions tell you to do, so you become accepted and are the “ideal” woman. That way everything is happy – kulshi bkheer – maybe you are not happy, but you are still accepted. The second path is you just have to lie to everyone and be the perfect person, but when people find out you will be kicked out and not accepted anymore. The third path is you have to challenge everything and fight against every tradition that wants to control, but you can only do this if you’re a position of power. You need your own job, your own place, and you have to be totally independent; this position is very difficult to achieve. But while you’re not in that position, you have to fight some things, like with the hijab and self-success and doing everything you’re told, but you have to lie about some other things. This way isn’t easy, but it’s all I can do for example without being in that position of power.

ME: I’m sorry for all you have to go through in Morocco. But even if that’s true, do you still love it here?

HALIMA: Of course, I do love it here. I love the people – well, not all of them but many of them – and how we all work together; I truly love that sense of collectivism in the Moroccan identity. I wouldn’t want to be independent and I don’t think life in America would have that level of collectivism, people doing things together and it being a defining part of your life and your identity. The food is very good, too, and there are many beautiful places in this country.

ME: Along with that sense of collectivism, what does it mean for you to be a Moroccan?

HALIMA: The language, the cultures, the traditions. Yeah – that’s all. The space or place of Morocco, too. You live here, the fact that you live here, makes you Moroccan.

ME: In that case, what does it mean to be a citizen of Morocco?

HALIMA: It means people who want to help the country and actually help make it a better place for other Moroccans rather than simply sitting around and using the system. It’s this giving back that is actually incredibly important to me and why I want to teach and eventually work for an NGO.

ME: As a citizen then, do you get involved with Moroccan politics?

HALIMA: No. I mean, I vote, but I’m not part of a party or anything. I actually don’t like politics and when I see it in the news I often try to ignore it. But I have been reading about Moroccan politics a little more lately; politics is often bad and causes other bad things, like poverty and inequality, so with an NGO I could help make people’s lives better, so I don’t want to be more involved in politics than that. I’m on the board of an association and we do our social work to help people, but we’re really not more involved than that.

ME: If you started your own NGO, what kind of NGO would you start?

HALIMA: A women’s rights organization. Not exactly sure would it do, but it would definitely be predicated on fighting against the patriarchal society. Women’s rights are human rights, so it would definitely fall under that category as well and provide services to help people.

ME: How do you want to improve human rights in the world?

HALIMA: We have to stop judging people based on their religion, their nationality, their ancestors, their ethnicity, their skin color. We should judge people based on their actions, what they do, what they take from and give to society. It’s been very difficult to see and hear about discrimination in the world, especially from Western nations like America and France. France, in particular, has to make change. When I was in America, it was a co-existing melting pot. In France, there are girls who are not allowed to attend university because they wear the hijab. And look at the World Cup; 80% of France’s team was African, 50% was Muslim. Outside of the praise these players get, there is so much xenophobia and racism in France that treats Africans and Muslims as sub-human and things have to change.

ME: Regarding France, a lot of these systems are deeply ingrained in society as the result of things like colonialism, so how can we work to help society work together and fight this problem?

HALIMA: Like I said, it all starts when we stop judging. We have to accept different religions, different cultures, and different people. We all need to have a open heart and an open mind. The changes immigrants make to culture are what make society, not degrade it. People should be free to do whatever they want, and embracing these differences is where we start to solve the problem. After that, we can finally all work together and then create a space for legal change all around the world.

ME: Does that mean you’re a proponent of global citizenshi

HALIMA: Yes, definitely. I think the world should remove barriers between different people and then in turn individual people will start adopting culture from others and become citizens of the world.

ME: Is it possible to be a global citizen and also a citizen of Morocco?

HALIMA: Well yeah. I will always be a Moroccan, but I can still openly enjoy parts of other people’s culture. We don’t have to be static and stuck in one specific culture.

ME: When I ask about citizenship, you largely address culture, so what does citizenship mean to you?

HALIMA: Citizenship is simply a community made up of citizens – people who contribute to a society/culture whether it’s from one country or the world – and citizens are the ones that create this culture, so that’s what I talk about it so often. They’re both based on people, so it all becomes one cycle.

ME: Last question. If I asked you to pick one word to summarize what it means for you to be Moroccan, what would it be?

HALIMA: Fighting. Fighting for rights but also fighting cultures and traditions. As much as I love Morocco, I have to fight every day. My love of its collective identity conflicts with my desire to be who I am, so that’s why fighting has to be the best word if I have to pick just one.

ME: Thank you very much for your time, Halima.

While I can’t generalize Halima’s experience and definition of citizenship to all Moroccans, it certainly is interesting to find someone with a fairly similar view on citizenship. I too believe that the citizenship in the informal, non-legal sense is based largely on community, identity, and belonging, but I also think it has a lot to do with internalization of a society within one’s identity. For example, how could I truly consider myself American if I’m opposed to the values that define America ideologically?

I think the fighting that Halima describes is complicated to consider whether it falls under my definition of citizenship or not – is she fighting practical implications of society or the society itself? I personally lean to the belief that she is in fact a citizen because culture and traditions are byproducts of society but not factors of a society itself. If you ask me, citizenship and culture co-exist, but they are not actually cyclical as Halima describes; their overlap is critical, but their distinction is even more so. That’s where my biggest disagreement with her definition of citizenship arises. I personally do not think culture is part of the definition of citizenship. Rather, I think it’s the direct product of citizenship, the result of the interaction of all the individual members of a society and their individual tastes, practices, customs, and beliefs. Yes, on occasion, a government legitimizes and emphasizes particular activities, but because these all derive from the people originally, they are only part of citizenship from a practical standpoint rather than the actual concept of citizenship. Nonetheless, I fully understand why Halima actually includes culture within her definition, because to a degree they are in fact inseparable.

My other major takeaway from listening to Halima was her complicated relationship with politics, or the collective action of a people within society through the implemented system of governance. As much as she expressed a distaste for large governmental institutions, she also demonstrated an incredibly strong inclination towards civil society, the buffer zone between a government and the people it is supposed to represent. When I pressed on considering this nuance, she said that there really is a clear distinction between the two, though I certainly disagree; I guess we just have a different definition of politics – I see it as collective action and align it with governance while Halima most likely only considers the practices of Moroccan government and its direct representatives. It’s interesting how so much debate really just comes down to semantics. Because I view every person who actively considers their role in society – yes, even those that actively avoid “politics” – a political actor, I have come to love politics and engaging in collective action because I find it integral to all human interaction. I fully understand why many people become upset with government, but I’m very happy that Halima has channeled that frustration into civil society to help people that are hurt by different policies – I wish everyone did that – even if she doesn’t believe that civil society is part of politics.

At the end of the day, I think it’s most important that people are involved in their respective national and global societies, and I know that Halima fully embodies that. That’s definitely my biggest takeaway.

When I sat down this week with my host mom, Nisrine, to ask her what citizenship means to her, I didn’t anticipate the remarkable narrative that would become her views on life in Morocco. She and her husband have lived in Morocco their whole lives; they now live in Fes with their two children, Zied and Rayda. Her husband makes shoes for the winter and she works part-time as a math teacher. When I asked Nisrine about how it feels to be a Moroccan citizen, she had a lot to say – both good and bad.

She said, “I like Morocco because it is an Islamic country. There is a mosque and we can practice religion safely. Nobody asks why you go to mosque or why you celebrate Eid or Ramadan. But there are many bad things. I grew up without a father. My father only visit Morocco for 45 days out of year. I lived without a father because he goes to France to search for work to pay for school for his children and to give money to his family. My sister married a man who also leave Morocco to find work. My brother leaves to Spain to find work and he tells me how everything is there – how the government treat the people. I hear it and I am upset because it is not that way in Morocco. I didn’t finish school because the school don’t give you money and you can’t stay in school if your family don’t pay for you to live. My husband doesn’t work with the government so nobody cares if he gets money or not. He make shoes for winter and doesn’t have work in summer very much. If you don’t work, you don’t get money. For work in Morocco, people don’t have a job because they deserve it – it’s because they have an uncle or brother who works there and they help them get a job. Especially in the government you need this.”

She pauses for a bit to think and I see the emotions battling in her eyes. She is so young, yet has given up so much, including her aspirations and a chance at a career of her own. I realize how blessed I am to be able to have a say in my future.

She continues: ‘Hospitals here are very bad. Nobody asks about you or the children. I took Zied once to the doctor and nobody would look at him. If you don’t pay money, no one cares. The nurses go to sleep or tell the old people or sick people to go away. But if you give them money, then they will look at you and tell you what is wrong. I went to the doctor when I was pregnant the first time. I had the baby and the nurse come in and say, “In France, the baby would’ve lived, but he will die here.” He died within 24 hours. I will never forget this sentence the nurse told me.’

The pain in her voice when she tells me about her first-born child is imminent and I know there is nothing I can say at this moment that will come close to soothing the hurt. She has every right to be hurt and angry. Nothing can give a mother back her child.

She seems to want to move on from the topic. I ask her about her involvement in the community and she tells me she thinks it’s important to help the less fortunate. She responds, “There is a proverb: don’t see the people who are rich – see the people who are poor. We help my husband’s family in the mountains. They are very poor. My family does not need my help l’Hamdu llah (thanks to God). They help provide for me and my family. I give clothes to children after Zied and Rayda don’t need. During Ramadan, I go to mosque as often as I can. It’s hard with children but I go a lot. My husband sometimes goes to every prayer during Ramadan. I call my brother every occasion and tell him to come visit me. You have to help your family and listen to them. In Morocco, you can’t say no to your parents. When my father tell me to get married, I didn’t want to but I have to do as my family says. I am just very sad my father is gone during Ramadan because he was without his family. He needs family to celebrate and a woman to cook the foods for Ramadan.”

Lastly, she voices her concerns for her children: “I am afraid for my children. I want them to go to school and university and finish. Because I couldn’t do this, it is a big hope of mine.”

This is her reality. I take so much for granted as an American. Because I am a citizen of America, I have countless “guarantees” that Nisrine can only hope for and this saddens me beyond words.

The Alif center, where I study Moroccan Arabic, introduced me to my language partner named Tsukina, a young twenty-two-year-old who recently graduated from university with a bachelor’s degree. She is a very bubbly and energetic woman who enjoyed talking with me in spite of my broken Moroccan Arabic. Upon interviewing Tsukina and asking her view of citizenship, the result was the following conversation. I have adjusted her dialogue to make the conversation more comprehensive, as there were sections where she had difficulty articulating her ideas in English.

Me: What does being a Moroccan citizen mean to you?

Tsukina: I feel happy because in Morocco, I feel that it is the safest within the Arabic World. Women are not forced to wear hijabs or djellaba or that they are not allowed to drive, like in Saudi Arabia.

Me: What is something you aren’t happy about in Morocco?

Tsukina: There are inequalities among people, the upper-class people and the lower-class people, this is a problem. There are lots of people without jobs, we get degrees but there are no jobs or opportunities for success.

*She later mentioned that she was among these people unable to obtain work, even after obtaining a bachelor’s degree. Tsukina said she planned on moving to Tangier if this continues, claiming there would most likely be more job opportunities in Tangier.

Me: What are some things you do like in Morocco?

Tsukina: I like my independence, when I think of independence, I think freedom. I do what I like and there’s nothing forcing me otherwise.

Me: If you could fix something in the government, what would it be?

Tsukina: The first thing is education, the education program. The education here is not good. There are places where the education is worse than other places, I think this needs to be fixed.

Me: Do you volunteer for any organizations?

Tsukina: I don’t volunteer but I plan to in the future during the summer.

Me: Are you engaged in politics?

Tsukina: I stay away from politics. I work hard in my job, but I don’t like to engage in politics. I feel like I would be forced to do things if I participate in politics/ or work in the government, that’s why I don’t like it.

Looking back on our conversation, I thought it interesting her idea of Morocco, particularly the topics of women and the jobless youth/educated persons unable to enter the job market. Tsukina being in her early twenties, I felt as though her experiences would provide insight on the current situation of Moroccan society.

As she shared her perspective of women and her own experiences, her views resonated yet simultaneously clashed with that of my own. Although I agree that, to an extent, women in Morocco have greater freedom than other states within the Middle East, I could not help but continuously compare their freedoms to those of western/American women. Her response forced me to think from the standpoint of Moroccan women and how they may interpret their position in society in comparison to other – less foreign or familiar – societies. Despite considering myself unbiased, this realization compelled me to rethink how Moroccan women might see themselves and not how I see them. However, her response also raises other questions. Such as, if Moroccan women see themselves in this fashion of safety or complacency, then would they be less inclined to maintain awareness/participate in politics? Or would they be more inclined to maintain political awareness or participation to avoid regression of women’s rights? Frankly, it depends on the context Moroccan women grow up within.

Particularly in Tsukina’s case, I wonder about her dilemma and the idea of many educated yet jobless Moroccans. She doesn’t think in political terms, but the philosophy she utilizes to justify her abstinence from the political realm contradicts itself. Although she clearly has opinions of the areas that need improvement, her actions of passive citizenship imply complacency with such problems. Which brings about questions regarding towards Moroccan society and whether they influence women or Moroccans in general to think in this manner? At the same time, myself being an individual participating in only a few groups impacting the community, am I entitled to criticize her thinking? I thought it interesting how her concept of citizenship forced me to think about my own, and how hypocritical I can be about my government even though my exercise of active citizenship is sparse. Perhaps realizing these faults is the first step towards active citizenship.

Overall, Tsukina’s perspective on citizenship rearranged my western perspective of other cultures, especially so in states within the Middle East where western created stereotypes tend to overload our perceptions of such areas. It was also a journey into my opinion over my actions concerning the political sphere, including my shortcomings and possibilities for improvement. I also believe the conversation that I had with Tsukina forced her to think about important topics that she didn’t usually spend time thinking about. Hopefully, this exercise gave her reason to ponder these topics more. After all, things can only start with the first step.

Tsukina declined to have her picture taken. Instead, this is photo I took in Chefchaouen that kind of reminds me of Tsukina

Amine Naini. Photo: 7/12/2018

As part of our Religion, Security and Global Citizenship in the Arab World class- one of the two classes I’m taking in Morocco this summer- we have been exploring what citizenship is and what it means to different people. Through our class discussion, we defined citizenship as the state of someone to have a sense of belonging to a given country as recognized by the laws of that particular country. Citizenship is a complex topic and different people have different interpretation of the term.

In an effort to get a diverse perspective, I talked to a couple of people, of different nationalities, and asked about their understanding of the term. One of these people was Aminie Naini, a Moroccan citizen who is a current student at the American Language Institute in Fez (ALIF), studying English. Amine is my language partner at the center where we help each other practice English and Arabic. When I asked the question, he didn’t really have an exact answer, just like I was earlier this week before we discussed the topic in class. After I tried to explain and put the question in context of what we would be discussing, Amine said that to him citizenship is “having the status of belonging to (his) country because of the fact that (he) was born in (that) country and having rights and responsibilities and using them to take a positive role in shaping the future of (his) country.” He went further and explained these responsibilities, giving examples such as voting during elections so that his country could have leaders that would bring change thus , like he said earlier, his decision to vote would have shaped the future of his country.

Citizenship is never static, it changes constantly in every society. Usually, of importance is the question of whether citizens’ active or passive participation in the different spheres of a particular country determines whether one is a good citizen or not. To evaluate citizen’s involvement, there are a set of apparatus that can be used to measure citizenship. These dimensions of active citizenship include participation in political life, civil society, the community and one’s values. I asked Amine a couple of questions in line with his participation in these dimensions and he shared some of the activities he has been involved with which he sees as his own way of contributing to the country and to his fellow citizens too.

Political Life: Amine has been exercising his right to vote and creating awareness during campaigns about voting out bad leaders.

Civil Society: He has both been volunteering with and making donations to a local organization called Shabab Al-Kheir that runs orphanages and organize cleaning and taking care of graveyards (graveyards are usually communal and there’s an importance attached to taking good care of them). Amine has also, severally, taken part in boycotting products such as gas and milk producing company, Central Afriquia and also Sidi Ali, a water producing company for either overpriced or low quality products.

Community Dimension: He has been participating in AIESEC community service events in Fez. He has also been contributing to his country culturally by interacting with many foreigners coming to Morocco and teaching them a lot about Moroccan culture and clearing out any negative stereotypes they have about Moroccans (we played a fun game called Stereotypes).

Values: Amine cares about human rights, both Moroccan and that of immigrants and feels that immigrants in Morocco should have the same rights as Moroccans because that is how he would also want to be treated if he went to another country.

While he thinks he has been actively participating and practicing his citizenship, he still feels that the government, through corruption and empty promises to the citizens, often makes it really hard for him to see the Morocco he wants!

I found Amine’s responses thought-provoking and I thought I should share them with you. Feel free to share your thoughts on my conversion with Amine and what you think citizenship means to you, in relation to your country!

“I love Morocco! I wouldn’t change anything about it.” Aya looked at me, presumably waiting for another question about her country. She seemed eager to share with me her culture and ideas, but at that moment I was at a loss for words.

“Nothing?” I asked her, incredulously. “There isn’t anything you don’t like about Morocco?”

“No,” she insisted, “there is nothing I don’t like!” It was unfathomable to me. If someone were to ask me about the United States, I would tell them I’m happy living there; but, undoubtedly, while I love being an American, I could recite a litany of things I want to see changed. There are issues in the United States that frustrate me, topics that are debated wildly among friends and strangers alike, things that politicians spend decades haggling over. Just because I’m patriotic does not mean that I think my country is perfect, that there aren’t ways for the United States to improve or progress. But, perhaps her answer was strange to me because after being in Morocco for two weeks, there were frustrations of my own I had about the country. I questioned my host-sister about being a young woman in Morocco. I wondered how she felt about people harassing her on the street, an everyday occurrence in Fes. “It is normal, it happens everywhere, so it doesn’t bother me,” she explained. Again, I did not know what to say. Her view on life was so vastly different from my own that it took me a moment to begin to comprehend. Daily Moroccan life is heavily influenced by culture and tradition. People do not think about life in terms of good and bad, things that need to change and things that should stay the same. It is all a part of their ageless culture, their identity. Change via government was not something that even crossed Aya’s mind. I asked her what age one had to be in order to vote in Morocco. “Nineteen, I think,” she informed me. But it did not seem like it was anything important to her. She was only seventeen years old, too young to vote anyway. She was just a normal teenager, she didn’t care about voting and politics. Her own life was more important to her. She was still in high school but she wasn’t a part of any clubs there. “I go to school to study and I come back. I don’t do any sports or anything like that.” I wondered about what she did outside of school. She told me that she spent most of her time with friends or going shopping in the souks. At home, Aya wore whatever she wanted, but whenever she went out, she threw a djellaba on top of her clothes like a jacket, making sure to cover herself appropriately. She told me: “We cannot wear shorts or things like that where we want because of our culture,” but she did not seem to resent it. No, it was simply life to her, a part of what it meant to be Moroccan, not something that needed to change. “In Morocco we have Islam,” she explained, emphasizing its importance, “it is a big part of who we are as Moroccans… They have it in other places like Egypt and Lebanon but it’s our culture and our language that makes us Moroccan, too.” I asked her if, one day, she would ever want to leave Morocco. “My sister,” she recounted, “she asks me if I want to come to Germany with her, but I don’t want to… Everything I know is here: my friends, my family, my culture. I love Morocco, why would I want to leave?”

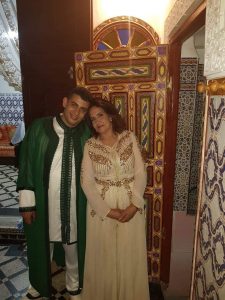

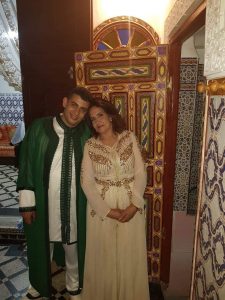

Wafi (host brother) and Rabiaa (host mother)

“May I interview you about citizenship?’

“Yes, yes of course,” Mohammed nods and adjusts his glasses as I reach into my bag for my laptop.

Mohammed is my language partner at the American Language Center in Fez. Outside of classes, he helps me review my darija in exchange for a chance to practice his English with a native speaker. His English is far better than my darija—he is receiving his master’s in English this year—but he is patient and helpful as I navigate the new words and phrases. We have just finished my darija lesson, but I have a few more questions.

“I have to interview a Moroccan about their opinions on citizenship for class,” I explain as I open a new Word Document. “Are you a Moroccan citizen?” It seemed like a good place to start.

“Yeah,” he says. “I was born here.”

“Are there any other ways to become a Moroccan citizen? For example, if I wanted to become a Moroccan citizen, could I?”

“Yes, yes, you could.” He pauses, thinking. “You would have to stay here for a long time, and then apply for citizenship, and…” he trails off, grasping for words. “It is a lot of steps, I don’t know the exact procedure, I’m sorry.”

“Mashi mushkil,” I tell him. No problem.

Mohammed eyes my fingers as they fly across my keyboard. “Are you typing everything I say?”

I pause and look up from my laptop. “Oh, yes, is that okay?”

“Oh, yes, yes, it is fine,” he says. “But, I feel bad. I want to give you good answers so you can do well on your assignment.”

I assure him that his answers won’t have any direct impact on my grade. “I just want to hear what you think.”

“Okay, okay,” he agrees, and we continue.

“What rights do you have as a Moroccan citizen?”

“Oh, well, I study for free, I benefit from Moroccan security and I am safe.”

I have to prod him to speak openly again before he continues, “What else? Oh, I don’t know if we have, like, a healthcare program. I’m not in one, but I don’t pay much for healthcare here. I don’t have a job. They don’t help us with that because we’re not part of the upper class. We don’t have connections.”

“Are there any rights that you wish you had as a citizen?”

“Well, for instance, two days ago, I got caught by a policeman for not wearing a helmet [on my motorcycle], and I had to pay a fine. Paying a fine is fine, but they don’t apply that law to everyone, and I don’t like that. I wish the laws applied to everyone.”

Fair enough.

“Do you think immigrants should be able to be Moroccan citizens? And have all of the same rights as you?” With all of the heated debate about immigration in my home country, I am eager to hear his answer.

He answers quickly. “No, not all of them, because not all of them behave in a good way. Like, there are three African people who killed—did you hear about this?”

I shake my head no.

“Oh well, a while ago there were three African people who killed one guy in Morocco. He was working as a guard in a place. So, these people should not be allowed to be here. But there are other people that are good, you can live with them. They’re from Senegal or Mali and they come here to study and get jobs, and they should be allowed.”

I nod slowly as I type up his response. Mohammed’s words almost echo the fears of those who oppose immigration to the United States. I know American people who claim that all Latinx immigrants are violent criminals who are out to steal American’s jobs, and then turn around and praise the hardworking nature of their ancestors who emigrated from Germany, Italy, or other European countries. I don’t know much about immigration patterns in Morocco, so I can’t make any deeper comparisons in the moment. And besides, I am not here to critique Mohammed’s opinions, only listen to them. I carry on with my questioning.

“What do you think separates a good citizen from a bad citizen?”

He ponders for a moment, then says, “I think that is someone who cares about the common goals of the country. Someone who wants to help his country to be developed and good, rather than just caring about yourself and your interests. So, yeah, I have my goals, I have my objectives, I want my plans to be successful, but I care about other people as well. So that is what makes a good citizen. Then there are people who abuse other people’s right, they are bad citizens, even though they have high status and positions.”

It is the second answer in which he has mentioned class in relation to Moroccan citizenship. I have heard similar sentiments from the few other Moroccan students that I have spoken to—that socioeconomic inequality is one of the major qualms facing the country. I decide to delve deeper into Mohammed’s civic engagement.

“Have you ever voted in an election?”

“No,” he answers flatly. When I press as to why, he offers, “I don’t vote because we don’t have transparency and credibility in the process. I don’t believe that the people who deserve to be on the ballot are there. I have never voted, and I don’t think I ever will as long as the system is like this.”

I ask if any changes could make him consider voting.

“I need to see the right person in the right place. Someone who deserves to be there, who is honest and credible and cares about people.”

He asks if I have ever voted. “Yep,” I quip, typing away. I find it interesting that the reasons Mohammed cites for not voting are the ones that motivate me to exercise my civic duty. I vote in an effort to ensure that the “right people” end up in power. I am a tad heartbroken that Mohammed has such a dismal outlook on democracy.

“Did you vote for Trump?” he inquires.

I laugh and shake my head. “No, no, no.”

Mohammed laughs, too. “Trump is a business man, yes?”

“Mmmhmm.”

He cracks a grin. “So he should run his business and let someone else run the country!”

We both laugh loudly, probably disturbing the students studying around us.

“Alright, alright,” I say, when we finish chuckling. “Please don’t hate me, but I have to ask the million-dollar question: what does citizenship mean to you?”

He smiles. “Citizenship to me is, to behave in a good way, living with other people and respecting their rights. And, at the same time, it’s being respected yourself.”

I nod in agreement. A solid answer.

For a moment the space is filled only by the sound of my typing. I am about to tell Mohammed that I am out of questions when he cocks his head to the side and asks a question himself. I hesitate, not sure if I am meant to answer or if Mohammed is having a moment of introspection. We are both quiet for a minute as we reflect inwardly on the meaning of his words:

“Am I a good citizen?”

Mohammed Sarbouti at the American Language Center in Fez.

Oumaima In class we often discuss the concept of citizenship and how it varies from country to country. ALIF, or the Arabic Language Institute of Fez, is the school where we are taking Moroccan Arabic. This school also teaches English, so we have the opportunity to interact with Moroccan students as well.

Meriam, our coordinator at ALIF, put me in touch with Oumaima, a second-year university student studying English. Because she had a meeting to attend, we were only able to talk for a short time. During this conversation, I learned that Oumaima is very outgoing. While we were speaking, several of her friends came up to chat with her or give her a hard time about missing some of drama rehearsal. True to Moroccan culture, she was so friendly, and I’m grateful she was willing to share her thoughts with me. In this interview, we talked about citizenship and Morocco and some of Oumaima’s activities outside of school.

Interview

Me: What does being a citizen mean to you?

Oumaima: To be a good citizen in Morocco, or in any country, we should respect people. It’s important to complete and maintain your duties; of course, it’s also important to follow the law.

Me: What responsibilities do you think your Moroccan citizenship entails?

Oumaima: Respecting people is important to me. In addition to this, I have to study and work hard, since this will help my society develop. It is because of me my society will be developed and successful. After all, the people who work hard are the important members of society.

Me: Do you think there are any generational differences between your ideas of citizenship and its duties and your parents or grandparents’ ideas? If so, what are they?

Oumaima: I’m not sure. Some people have the idea that if you belong to Morocco that we are not that important. They think that even if we work hard and study hard we will never get a job. They just think they should emigrate because they don’t trust their country.

Me: Can you tell me more about yourself?

Oumaima: I’m a very hard working. This helps because even if I’m feeling down, I know I’ll be okay in the future. I’ll get my chance like the others. As an example, even if I work hard and don’t get a good mark on a test, it’s okay. I still have chances. If I don’t have hope, I’ll never survive.

Me: When did you start learning English?

Oumaima: About a year ago, when I joined the drama club. Before the drama club, I couldn’t even speak English. Back then, I was a shy person, and I was so timid. I started expressing myself because of drama club.

The theme of citizenship is constantly on our minds. As we grapple with this concept and discuss it, it’s easy to agree with those that surround us when it comes to these topics. People, by nature, tend to surround themselves with those that are similar to them. That’s why it’s important to have these conversations with people we know could be radically different. That is why I interviewed Fati, my Moroccan language partner, on the theme of citizenship.

According Fati, “citizenship… is like a big group in which all people that live/ belong in one country should have the same rights and duties. Also, justice and equality between different social group, not only men and women.” When I asked her how one can partake in citizenship-like activities she said, “Can we consider voting? You need to vote to show your opinion and your perspectives about your country for the future. Also volunteer work. There’s an opportunity for each citizen to show their concern for country and community.”

Fati is part of the community service club at ALIF, and she said she sometimes partakes in service activities, but “not a lot. Sometimes I do.” She partakes in “blood donations, and teaching English to children, to people that can’t afford money to study English.”

When asked if she voted, she replied, “yes, but when I was 18 I had to vote but I didn’t. I didn’t trust the politicians. All of them were corrupt people. My vote wasn’t going to make a change. In the end, these people represent you. There are people who will both agree and disagree with that.”

She’s not part of a political party, but if she likes a candidate, she’ll vote for them. Not really, If I like the candidate, she’ll vote for them.

Overall, Fati’s thoughts and feelings were similar to those of mine. It was surprising to see this since we come from different backgrounds, and the governments in both our countries aren’t very similar.

For the past few weeks, in between touring new cities and learning our way around Morocco, we have also been taking classes! In one of our two classes, we have been discussing the meaning of citizenship, both in the United States and Morocco. For our blog posts this week, we each interviewed a Moroccan citizen about their views on citizenship in Morocco, as well as their personal political and community engagement.

I chose to interview Muhamed, my Arabic language partner here in Fez. After working on my Darija for a few minutes, we started the interview. First, I asked him what citizenship, specifically Moroccan citizenship, meant to him.

He replied that it meant doing his duties to help his family, because through helping his own family, he believed he would also help others. He added that being a good citizen in Morocco means being polite, respecting all people, being “strict” with yourself, and being active in Muslim faith. I asked him to elaborate on that last point, since my experience of citizenship is very different and doesn’t involve active participation in any specific system of faith. He explained that he believes that embodying ideals and actively practicing Islam would lead someone to also embody traits of a good citizen.

Next, I asked him about his level of political involvement, including voting in elections, volunteering, or supporting specific political causes. Muhamed said that he had never voted and had no plans to in the future, because he believes that his vote will not change anything about the country. However, he did say that he would vote in another country if he were to move one day.

I asked if he had participated in any organizations, protests, or boycotts centered around changing aspects of society. I had heard that many people in Morocco were currently boycotting a brand of bottled water because of its high prices and brought this up to ask his thoughts. He said that while most people have goals for change in Morocco, he has not participated in any similar protests and didn’t plan to, because he doesn’t think that they are effective in bringing about change.

When asked if he was active in any community organizations revolving around religion, sports, service, work, culture, or any other topics, Muhamed told me that he is part of a community service club but isn’t very active. He said that he prefers to volunteer individually in his neighborhood.

Finally, I asked Muhamed about values in Moroccan society- which ones are important, which ones are lacking, and what he thinks needs to be changed in Moroccan society. The first value he brought up was respect, and how certain groups of people in Morocco- giving the example of the LGBT community- is often not treated with respect and faces violence in the country. I asked what he thought could be done about issues like these, he said that he thinks the government is doing a good job by helping them indirectly and “trying to be secular.” He said that although groups like women and the LGBT community face many issues, that the “law is on their side,” meaning that in the case of a crime, the law would protect victims. I asked if there were any other things Morocco could do to address such issues if the law was only partly sufficient, and he said that his English wasn’t good enough to express the other things he was trying to say on the topic.

Muhamed’s final thoughts on citizenship in Morocco were that “it you respect yourself you must respect others, and if you do those things it will reflect well on society.”

I really enjoyed speaking with Muhamed and it was really important to me to hear his thoughts on citizenship in the country I’ll be living in for the next month. I know that he had a lot of other things to say that his English didn’t allow for. I wasn’t too surprised by his answers. A lot of the Moroccans I have met have either been very optimistic about change in society or have more of an attitude that society is unlikely to change. Muhamed’s thoughts helped me start thinking more about citizenship in Morocco, and its differences and similarities to citizenship in the United States.

A simple definition of citizenship might plainly reveal that a citizen is just someone who officially is a member of a nation-state. However, what does that entail? As a member of a nation, are you required to actively engage in national affairs? Or, more so, do you hold a moral responsibility to maintain active citizenship? I asked these questions to one of my fellow students at ALIF in Fez, a Moroccan native named Yassine. He is studying at ALIF to learn English and work towards a degree to have a better chance at earning a successful living here in Morocco.

Initially, Yassine was confused by my basic “What does it mean to be a Moroccan citizen?” question. He was unsure about how to answer the question correctly. After reassuring him that there were no wrong answers, I just wanted to hear his honest opinion. Yassine said that one of the main duties a citizen should have is to be a good representation of your nation. He went on to say that as a Moroccan citizen, it was his duty to show other Moroccans how to act. Also a good citizen would prove to foreigners he meets that Morocco is full of good people.

After giving his answer, Yassine was unsure about what to say next. He knew that he wanted to say more, but did not know exactly what to talk about. I then asked him about his government in Morocco, did he feel that he could be a good citizen under this government?

Yassine believed that he could only be a true citizen under a complete democracy. He said that the government in Morocco was authoritarian, making it impossible to be a true citizen here. Yassine went on to say that, while his views were liberal, they were the same as his parents. This helped debunk my idea that all Moroccan youths are rebelling against the more traditional views of their parents.

Then, I asked Yassine what he thought the biggest problem his country faced, and how a citizen should try to advocate for change?

He replied that the biggest problem in Morocco is that the government is not creating enough jobs for the youth, the millennials, the future. He said that all over the nation, there are fruit stand vendors who are certified lawyers, PHD graduates, and MBA graduates, showing the number of highly educated adults who fail to find jobs that fit their skill level.

Finally, I asked Yassine how he thought Moroccan citizens could help change this narrative, and how they could make the government change?

He said that they needed to make the government aware of their problem. Not through active protests in the streets, he said that would lead to violence and that was the last thing he wanted for his country, but instead through smaller scale protests that genuinely made a difference. He informed me about a boycott the youth of Morocco were participating in over a water bottle company. Yassine was immensely proud of this boycott, telling me that it was really impacting the country and causing change.

Thus, Yassine showed me an interesting perspective about what it is like to be a citizen in Morocco. He showed that, even though he does not vote, actively follow party politics, or engage other activities commonly found by active citizens, he was truly a citizen of Morocco. He showed that Moroccan youth needed to advocate for change in smaller scale protests, not by forcing violence in their city streets. Overall, Yassine emphasized the importance of actively participating in some form of social advocacy. Thus, it shows that in Morocco, the meaning of citizenship has no simple answer.

Here is Yassine, the ALIF student I interviewed

Religion and Power in Morocco, by Henry Munson, Jr., at its core is a book dedicated to chronicling the political role of Islam throughout Morocco’s history. A daunting task, Munson largely relies on the analysis of previous texts such as Clifford Geertz’s Islam Observed and Ernst Gellner’s Saints of the Atlas, many others in Western languages, and numerous Arabic sources to ensure a comprehensive understanding of religious and political history in Morocco (Munson also bases part of the book on personal experience in Morocco though this is largely undeveloped throughout the book). Throughout the book, Munson critically analyzes this history through the lenses of anthropology and also ethnography; he makes many arguments in regards to the ideas of past scholars and forms his own intellectual conclusions. Throughout this process, Munson creates a narrative that is difficult to follow in its entirety and one that is also inadequate when considering the full scope of the book’s title; despite this, Religion and Power in Morocco is still an important piece of literature for anyone interested in Islamic or Moroccan history and even still a somewhat entertaining read in respect to academia.

By utilizing specific examples in Moroccan history, Munson uses his vast knowledge to not only address both the actual history of Morocco as well as the perception of history from a folklore perspective but also expand these examples into broad concepts that reflect important truths of Morocco (similar to Geertz’s approach). Yet he does this at the cost of not constructing one logical, cohesive narrative by which Religion and Power in Morocco develops. Not including the first chapter addressing 17th-century scholar-cum-saint al-Yusi, the book does transition in chronological order, but because of an overload of various information and the inability to smoothly transition between examples and concepts, it is difficult to follow Munson’s train of thought and the book diminishes in quality despite how interesting the history is and how thoughtful Munson’s conclusions are. The first two chapters of the book jump back and forth between different concepts with seemingly no rhyme or reason. In the first chapter of the book, by addressing a mix of concepts, critiques of Geertz, and the story of al-Yusi, Munson eviscerates an interesting folktale by making it confusing to process and renders it almost unenjoyable. The second chapter does not help things make sense for the audience; an expository list of scholars without much order and essentially no context does nothing to lessen confusion. And this confusion is only worsened by the assumptive nature in how Munson addresses his audience. This book was clearly written within the scope of anthropology, and the works of many people are written from the presumptive stance that these people (including Westermarck and Combs-Schilling) and their works need no introduction. For the audience members who do not know these names (myself included), the overload of content – let alone expected background knowledge – is overwhelming and makes Religion and Power in Morocco even more difficult to analyze. The resulting difficulty in processing the vital information provided in the narrative is the single largest flaw of the book. It would be difficult to explain how exactly to reorganize the information within chapters one and two, but the remaining chapters all function well as individual readings rather than one extended narrative. Regardless, the book has a lot of room for organizational improvement that would make it much better overall.

The other major critique of the book is not necessarily any of the content within it but rather the scope of the literature itself. As difficult as it must be to acquire detailed sources on pre-Alaouite dynasty history, a book called Religion and Power in Morocco cannot simply address the nuance only within the Maliki Sunni Islam practiced by the vast majority of Moroccans and its relationship to a single dynasty that has only been in power for such a small segment of the country’s entire history. The book fails to touch any intricacies of the relationship between religion and government in Morocco pre-1600, which is arguably the more critical history and certainly the one I was more excited to learn more about before opening the book. Before the presence of Islam in Morocco, the Amazighs (Berbers) who lived in the present-day nation practiced traditional religion, Christianity, and Judaism, and faith most likely played a role in tribal political organizations. While this information has been understandably lost to history, there should be much more available information in regards to the intersection of religion and power in Morocco’s pre-Alaouite dynasties. However, all of Morocco’s non-Alaouite history is “covered” in two pages (Munson 40-41), despite the fact that this period of time had far more drastic political and religious changes. In particular, Munson fails to include the history of Judaism in Morocco, which has had an incredibly important presence in the country and undoubtedly an influence on its political institutions. Jewish individuals were often ambassadors or “ministers” of Morocco to foreign countries, and at one point, the vizier (akin to a prime minister) of Morocco was a Jewish man named Aaron ben Battas; the financial success of Moroccan Jews ensured that they had a role in government and economy for hundreds and hundreds of years. So while it is difficult to decipher the intersection of Judaism itself and Morocco’s institutions of power, simply omitting the kingdom’s Jewish history is an egregious error on the part of Munson. At the very least, the name of the book is certainly a misnomer – there’s a lot of elements concerning religion and power in Morocco not addressed in the book. Though less catchy, a much more accurate name for the book would be The Political Role of Islam under Morocco’s Alaouite Dynasty. This new name is indicative of the fact that the book only addresses one religion within one dynasty. It’s also a fair reflection of the fact that most of the book doesn’t address purely political or religious aspects of Moroccan society; even though these elements are recognized as important on the first page of the preface, they are not actually detailed until chapter five (Munson 115-148) of the book. By having a clash between the scope of the literature’s title and the scope of the actual literature, Munson further distracts the reader from the book’s high quality, and a more in-depth analysis of Morocco’s pre-1600s history would improve the context from which the literature is derived.

Nonetheless, despite these critiques, Munson’s Religion and Power in Morocco is still a comprehensive, intriguing, high-quality text that addresses *almost* all of the history necessary to understand Morocco today. Further, Munson’s meticulous analysis of historical examples such as al-Yusi and al-Kattani through the lens of anthropology and ethnography shed light on interesting truths about Morocco that make for an very informative read that also would have been fully entertaining if the book were organized differently or perhaps just split into separate readings by the chapter. The unique political role of Islam still shines through; Munson’s thorough analysis starting in chapter three and extending through the end of the literature more than makes up for organizational flaws in the first two chapters as well the later chapters (rather than being entirely separate, some of the Combs-Schilling section from 121-125 should be at the start of chapter five). Chapter four in particular when addressing the flaw in Gellner’s theory of the pendulum between popular and orthodox Moroccan Islam & the development of ideologized Islam is Henry Munson, Jr. at his strongest; he effectively displays the development of reformist ideology through several critical scholars in a logical order (something that would have been beneficial to chapter two) and both informs and entertains the reader simultaneously. If Munson were to reorganize the book in such a way that preserves all the information without sacrificing entertainment and also decently expand the literature’s pre-Alaouite history section, then Religion and Power in Morocco would be a perfect book. But for what it’s worth, the book is still pretty good as is and still deserves to be part of any collection concerning Moroccan history.

“Mauretania.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 9 Aug. 2007.

“Morocco Virtual Jewish History Tour.” Jewishvirtuallibrary.org, American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise

Munson, Henry. Religion and Power in Morocco. Yale University Press, 1993.

|

|