“I love Morocco! I wouldn’t change anything about it.” Aya looked at me, presumably waiting for another question about her country. She seemed eager to share with me her culture and ideas, but at that moment I was at a loss for words.

“Nothing?” I asked her, incredulously. “There isn’t anything you don’t like about Morocco?”

“No,” she insisted, “there is nothing I don’t like!” It was unfathomable to me. If someone were to ask me about the United States, I would tell them I’m happy living there; but, undoubtedly, while I love being an American, I could recite a litany of things I want to see changed. There are issues in the United States that frustrate me, topics that are debated wildly among friends and strangers alike, things that politicians spend decades haggling over. Just because I’m patriotic does not mean that I think my country is perfect, that there aren’t ways for the United States to improve or progress. But, perhaps her answer was strange to me because after being in Morocco for two weeks, there were frustrations of my own I had about the country. I questioned my host-sister about being a young woman in Morocco. I wondered how she felt about people harassing her on the street, an everyday occurrence in Fes. “It is normal, it happens everywhere, so it doesn’t bother me,” she explained. Again, I did not know what to say. Her view on life was so vastly different from my own that it took me a moment to begin to comprehend. Daily Moroccan life is heavily influenced by culture and tradition. People do not think about life in terms of good and bad, things that need to change and things that should stay the same. It is all a part of their ageless culture, their identity. Change via government was not something that even crossed Aya’s mind. I asked her what age one had to be in order to vote in Morocco. “Nineteen, I think,” she informed me. But it did not seem like it was anything important to her. She was only seventeen years old, too young to vote anyway. She was just a normal teenager, she didn’t care about voting and politics. Her own life was more important to her. She was still in high school but she wasn’t a part of any clubs there. “I go to school to study and I come back. I don’t do any sports or anything like that.” I wondered about what she did outside of school. She told me that she spent most of her time with friends or going shopping in the souks. At home, Aya wore whatever she wanted, but whenever she went out, she threw a djellaba on top of her clothes like a jacket, making sure to cover herself appropriately. She told me: “We cannot wear shorts or things like that where we want because of our culture,” but she did not seem to resent it. No, it was simply life to her, a part of what it meant to be Moroccan, not something that needed to change. “In Morocco we have Islam,” she explained, emphasizing its importance, “it is a big part of who we are as Moroccans… They have it in other places like Egypt and Lebanon but it’s our culture and our language that makes us Moroccan, too.” I asked her if, one day, she would ever want to leave Morocco. “My sister,” she recounted, “she asks me if I want to come to Germany with her, but I don’t want to… Everything I know is here: my friends, my family, my culture. I love Morocco, why would I want to leave?”

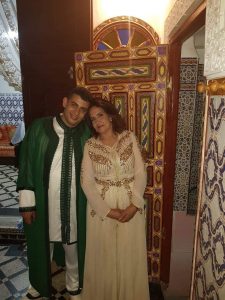

Wafi (host brother) and Rabiaa (host mother)

It’s really interesting to get the perspective of a young person from Morocco. Well written.

Another very interesting and well written post. It is fascinating to see Morocco through the eyes of a Moroccan.