Author: Matt Hebert

New media are often conceptualized in terms of the media they replace. Movies were once viewed as an extension of what could already be done by stage theater. Early television series mirrored the tropes of serial radio dramas. The case is no different with video games, which have in many ways emulated the standard narrative devices of film and literature while supplementing them with competitive elements akin to most sports. But like all new media, video games are not just an assemblage of old tricks — there strength as a medium stems from what they do that other media cannot. For games, this is the element of choice. By providing the player with choice, or the illusion of it, games possess an intimate mode of storytelling and expression which cannot be achieved with more conventional media. This paper will explore the ways in which games can employ choice to explore morality, develop immersion, experience powerlessness, and subvert traditional narrative structure.

When examining choice in games, there is one obvious limitation – most games are pre-rendered, every possible outcome anticipated in lines of code. “When we play games, we operate those models, our actions constrained by their rules: the urban dynamics of SimCity; the feudal stealth strategy of Ninja Gaiden; the racing tactics of Gran Turismo.” (Bogost 4) If this is the case, then it appears to defy intuition that a player can have any true choice. Whatever semblance of freedom the player may have, they are ultimately confined to the options that the games developers had the foresight to account for. This may give players the illusion of choice, but wouldn’t it also deny them true agency? A game’s world is certainly confined to its specifically laid out rules, but is the “real world” much different? No one truly has the freedom to do whatever they wish. Individuals are confined by the laws of physics, their resources and their abilities. If we accept that individuals can possess agency in a reality without absolute freedom, why is a video game arbitrarily too restrictive to allow for genuine choice? Many games can accommodate every choice a player is reasonably likely to make, meaning a player may never even notice that they lack a truly free choice.

Choice and Immersion

Of course, even if a player appears to be given some choices, they are rarely, if ever, given every choice. Most games are inherently interpassive. Laeititia Wilson of the University of Western Australia defines interpassivity as “a mode of relating that involves the consensual transferal of activity or emotion onto another being or object – who consequently ‘acts’ in one’s place.” (Wilson 2) This mostly manifests in games through pre-rendered actions or scenes. Players project an identity onto their avatar within a game. When this avatar acts without the player’s direct control, players must forgo their agency and accept these new actions as part of the identity they project onto the avatar. In directly plot-driven games, players are expected to identify with the playable character and take the character’s responses to situations as a cue for how they themselves should feel as observers and implicit participants. A movie-goer might interpassively engage with a film by taking emotional cues from its protagonist, but a game can develop this connection on a deeper level because the player is both observing and acting through their avatar. Many games allow players to customize their avatars. A player can design an avatar that reflects their idealized self, or choose whether to play as a burly knight or a stealthy assassin. All of these choices serve to build the connection between player and avatar. The longer a player spends controlling their avatar, the more their motivations become entangled with the character’s. In this way, a game can present a character’s emotional reactions not only as something that can be related to, but as an extension of self for the player.

From a traditional standpoint, the ability for players to control their own experience with a game appears to be an obstacle to meaningful art. Most media are carefully crafted to convey precisely what the creator intended — the perfect shot, the perfect phrase, the perfect order. By ceding control to the player, game makers forgo this level of precision. Even if most of the game’s story is told through pre-rendered cutscenes, any segment in which the player is in control will be a unique experience. Great video games will never be precisely crafted in the same vein as the classics of Stanley Kubrick or James Joyce. However, this is because a game’s priority is not with the work presented to the viewer, but with how the player fits into it.

Choice and Morality

Endowing the player with choice, and therefore culpability, can give the player personal emotional investment in the story. Take the game Shadow of the Colossus, where the protagonist is told to hunt down and kill 16 beasts called colossi. (Sony) There is little to do in the game except kill these creatures, so player is only really given three options: wandering around, slaying the colossi, or turning off the game. Nonetheless, most players will never even question whether killing the colossi is morally right. It is a video game, afterall. As the man with the magic sword, of course the player should battle these monsters. They must be evil. It isn’t until the player has slain many of these colossi that the game begins to explore the implications of killing these creatures. Several colossi will not attack unless provoked. Several appear to fear the player, and fight only for survival. One colossus does not even fight back as it is being slain. The lengthy journeys between colossi, featuring minimal soundtrack and virtually no living creatures but the protagonist and his horse, give the player ample time to ruminate on the implications are of killing what appear to be the last vestiges of life in a barren wasteland. The only real way for the player to avoid killing the colossi is to stop playing the game, but the ethical questions that the game raises hit much harder when the player is first allowed to act without considering them. The player might ask, “Was I rash to assume these creatures were monsters? What do I actually know about them? In another life, what else might I have done without question?” The game may only present the illusion of choice, but the illusion is potent enough.

In other cases players are expected to be torn morally by the choices given to them. This was the intention for the creators of survival-horror game No More Room in Hell, which controversially included killable zombie children. (NMRiH) This is a game which focuses on survival rather than combat. Ammunition and other supplies are scarce enough that the best option is often to flee a zombie rather than to fight it. Nonetheless, it is likely that a player will eventually be faced with a situation where they must either “die” or attack a creature that looks uncannily similar to a human child, a difficult split-second decision if the player has become immersed in the game’s world. Creator Matt Kazan has defended the inclusion of these child zombies, stating that “Part of our goal was to create a zombie game not based on killing and action, but on tension and fear and moral and ethical choice. We are attempting to simulate a real-world collapse of society as a result of a lethal epidemic… Reading some posts by players off-put by the zombie children, being unable to shoot them on first encounter.. that is something that we set out to achieve.” (Kazan 1) The game confronts its audience with the horrifying means to fight for survival, forcing the player to examine which they value more, their life or their principles. The sadistic choice presented in the game is in fact more palatable than the one faced by any soldier who has ever come face to face with a child soldier. The medium allows gamers to understand how someone could do the unthinkable, or falter in the face of death, by experiencing it firsthand.

- [2] An example of a “child” class zombie, which many players hesitated or refused to attack.

The Absence of Choice

Because games are characterized by control, they can also explore themes by removing the player’s control over the game, causing them to experience powerlessness. For instance, in the main campaign of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, there is a sequence in which the player is in a city at the moment of a nuclear attack. (Infinity) After a cutscene showing the detonation of the bomb, the player regains limited control and is able to stumble from the wreckage, pulse pounding, and witness the surrounding devastation. The player cannot draw a weapon or try to escape, only hobble feebly for a few seconds before collapsing, dead. To give this moment context, the game has until this moment treated death as only a minor obstacle. If the player is fatally wounded, they will respawn nearby in a few moments, free to fight again as if nothing ever happened. By contrast, the shock of this more accurate depiction of the costs of war is devastating. The game confronts the player with their own mortality, and it is particularly equipped to make them feel more vulnerable because it has first trained them to feel invincible.

Video games are able to simulate mental powerlessness as well as physical. Rememori is an online matching game/interactive poem which deals with the degeneration of the brain in the face of Alzheimer’s Disease. (Rememori) For each level, the player is able to choose an avatar from a list of users ranging across the spectrum of intimacy from “Father” to “Doctor” to “Stranger”. The player’s choice of avatar will affect the sporadic pieces of text which are generated during gameplay. The actual body of the game is a memory game involving matching pairs of cards with identical images. Everything is neurological in nature, either depicting the anatomy of the brain, or embodying an idea which the sick character must struggle to hold on to. With each advancing level, the interface incorporates multiple methods to portray the degeneration of the mind. The card placement becomes more erratic, the images more volatile, the phrases less complex. In conjunction with one another, these components form an intuitive shorthand for the state of the mind at different stages of the disease and allow the player not only to understand it, but to feel it for himself. The game is especially poignant in that it gives the player a small amount of choice, only to steadily remove that choice near the end of the game. Users begin to blend together as relationships lose meaning, cards become blank as thoughts fall apart. Nothing the player does really matters once the sixth level is begun. The player can make the arbitrary distinction between “Stranger” and “Visitor”, but in either case there is nothing left to do but click each circle one last time and watch the brain fade away. In the same way, life is sometimes unfair, uncompromising, and unwilling to wait. When a degenerative disease takes hold, one can no longer hold back the inevitable just by wanting more time. At some point, it is necessary to simply let go.

Choice and Freedom as a Narrative Device

Games are one of the few media (perhaps the only one) truly capable of non-linear storytelling. Many films and novels use non-sequential storytelling, in which the events are presented out of chronological order. Nonetheless, there is still a predefined order in which these scenes appear, meaning that the story is still strictly defined and the ultimate narrative presented to the viewer is still linear. A game’s creator, however, can leave the pieces of the story lying about for the player to find. For instance, in the game Psychonauts, the player acts as Raz, a young psychic in training, as he dives into people’s minds, exploring worlds which embody the elements of their psyches. One level takes place inside the mind of Raz’s hyper-enthusiastic camp counselor, Milla. It is a saccharine world, full of disco-lights and never ending dance parties, with one hidden exception. The player may stumble upon a hidden room far removed from the festivities, which they are warned is “no fun” and “a real party killer”. If the player still chooses to explore, they are confronted with Milla’s worst memory — she was the caretaker of an orphanage which burned down, killing all of the children she was supposed to protect. (DoubleFine)

Below the hidden room is the embodiment of Milla’s guilt, a hellish pit where whispering voices torment her. Knowledge of this place gives new meaning to the images of children the player may have noticed throughout the level, and paints Milla’s exuberant disposition as either an elaborate facade or a reflection of extreme denial. The strength of this method of storytelling is the shock and gravitas that it carries from being found through exploration. Information is not simply presented to the player, it must be discovered and unraveled. The process of stumbling upon new information and searching for new clues engages the player with the material, giving them an added sense of investment in the final outcome. (DoubleFine)

Similarly, the ability for players to determine how they navigate a game assists the game’s creators in world building. When given the freedom to explore, the player can examine the world of the game at whatever level of detail they see fit. In a film, the director determines how to depict the space the characters occupy. There is a defined sequence of expository shots, and there is no way for the audience to see anything that is off camera. If the filmmaker wants the audience to see, for instance, a warning scrawled on the walls of dark corridor, then one of two things must happen: either the camera must deliberately pause and focus on the wall for the audience to see, or the director must assume that the viewer will pause the film and examine the background. In the first case, the director leads the viewer by the hand, pointing them toward what is important rather than letting them discover it for themselves as they could in a game. In the second case, this requires the viewer to break their immersion in the film, halting the progress of the story and no longer viewing the film as a film. While neither of these methods inherently detracts from a work of art, they serve specific artistic purposes and limit the audience’s ability to immerse themselves in a game’s world.

Of course, choice is not always a good thing. Too much freedom can hurt the flow of a narrative. If the player’s character becomes stronger by defeating enemies and collecting loot, then naturally the player will want to defeat as many enemies and explore as many areas as possible. This can lead to an unfortunate tendency for players to ignore narrative cues in order to explore every inch of a game. Suppose the player comes to a fork in the road, and the narrative would clearly have the player’s character going to the right — say, to rescue a captured teammate. Then the seasoned gamer, having been trained over the years to leave no stone unturned, will first go left. Who knows when the player will get the chance to come back and explore this area again? By following the story, they could miss out on a hidden item, or heaps of valuable gold, or a chance to become stronger. Taken to the extreme, this can leave the player dawdling around, unmoved by their partner’s impending peril, breaking their immersion in the story and providing unpredictable hiccups in the narrative. When a game includes many of these sidepaths, this can leave the story chopped into bits, separated by hours of scavenging and backtracking.

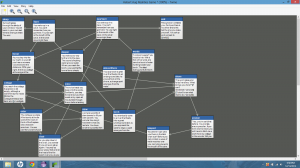

The Cave

I have created a short game to illustrate the use of choice in a game, particularly to emphasize when choice is only an illusion and can be used to instill a sense of powerlessness in the player. The player wakes up in a cave and is given a series of choices, although the choices have limited impact on the path that the player can take. Every series of decisions ultimately returns the player to the beginning of the game except for choosing not to play. This still more a rough prototype than a full game, but it illustrates the way that an apparent choice can in fact be no choice at all. This can draw the player’s attention to the medium they are using as well as encourage them to think about the impact their decisions have in everyday life.

Conclusion

Choice, or the illusion of it, is the defining aspect of video games as a medium. This separates games from other media, resulting in a different set of strengths in storytelling than more traditional media such as film or literature. By giving the player control, games are able to more intimately engage with their audience, opening up the possibility for works of art which interact with the player directly, implicating them in moral choices or forces them to feel powerless. The greatest movies are able to teach their audience something about their creators. The greatest games are able to teach their players something about themselves.

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. How to Do Things with Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2011. Print.

DoubleFine Productions. Psychonauts. 2005. PlayStation 2.

InfinityWard. Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare. Activision. 2007. XBox360.

Kazan, Matt. “OFFICIAL: Children Zombies”. Steam Community Online. http://steamcommunity.com/app/224260/discussions/0/684839199339308445/

NMRiH DevTeam. No More Room in Hell. 2011. Computer Software.

Rememori. Crissxcross. http://www.crissxross.net/elit/rememori.html

Sony Computer Entertainment. Shadow of the Colossus. 2005. PlayStation 2.

Wilson, Laetitia. “Interactivity or Interpassivity: A Question of Agency in Digital Play.”Fine Art Forum 17.8 (2009)

Images

[1]http://images.wikia.com/teamico/images/b/b0/CelosiaFire.jpg

[2] http://i1.ytimg.com/vi/M2XJ2z-e79M/hqdefault.jpg

[3] http://i.crackedcdn.com/phpimages/article/8/5/6/211856_v2.jpg