Information about/from our playwrights.

Annie Baker

Elle Magazine profile (Aug. 2013).

“I am an incredibly self-conscious person. Hyperobservant and self-examining. Writing takes me out of my head.”

For most playwrights it’s just the opposite, but Baker will gorge on reading for months before she even starts to write; then she tries to escape any “ideas” she has acquired in favor of building a world within an imagined physical space—the dueling theaters of The Flick, for example, or the fluorescent-lit community room of Circle Mirror. The obvious arguments and underlined messages of traditional dramaturgy don’t interest her as much as the creation of minutely detailed living realities. “I tell students: ‘If you have any comment to make, write an article.’ Playwriting is about the present tense, one present after the other, and will eventually become a present tense for a group of people in the theater.”

Her New Dramatists profile.

A profile in The New Yorker (Feb. 2013) — you can access the full article via Duke Libraries database but I’ve cut a section and added bolding to feature some important observations.

Annie Baker, a thirty-one-year-old playwright, […] wants life onstage to be so vivid, natural, and emotionally precise that it bleeds into the audience’s visceral experience of time and space. Drawing on the immediacy of overheard conversation, she has pioneered a style of theatre made to seem as untheatrical as possible, while using the tools of the stage to focus audience attention. “Circle Mirror Transformation,” Baker’s 2009 ensemble piece set at a community-center drama class, won three Obie awards, and was, in the 2010-11 season, the second most produced play in America. […]

A lot of critics, trying to pinpoint Baker’s appealing blend of naturalness and precision, have called her a “realist” or a “naturalist.” She thinks neither label works. “I feel like we lack any terms for playwriting that come after 1890,” she says. “Realism, naturalism–are you talking about, like, Ibsen?” To watch Baker’s work is to be drawn into a world that feels as unplotted as real life (characters chat at cross-purposes; costumes and stage settings are uncannily real) but that breaks abruptly into surreal transcendence (a hula hoop being spun for almost a minute, in one case). Onstage, Baker exercises meticulous control in order to make action seem as unrefined as possible. Her characters exchange the kind of knobby dialogue you overhear in diners on Friday mornings: mothers fretting volubly about their young-adult kids’ problems, twentysomething friends chasing back bleary silence with defensive nonchalance. (“I’m really hung over so you guys will have to excuse me if I’m like a little low-energy.”) Her goal is to explore what’s left unsaid along the edges of conversation: it’s the principle of looking at familiar stars so that the galaxies that can’t be seen head on appear out of the corner of your eye. The work requires tight coordination–not just of scripted words and silences but of movements, gestures, costumes, music, and the whole immersive apparatus of the modern stage.

A profile in The Last Magazine (May 2011) which has a picture by Matt Kaelin that totally reminds me of our approach to Vanya:

But while Baker is quick to point to fortune and chance as her guardian angels, her work demonstrates that she has an innate ability for crafting language into phrases that are both casual and nuanced. “One of the reasons I’m attracted to playwriting is how fragmented and grammatically lame it is,” she explains. “I’m interested in bad grammar and I’m interested in cliché and I’m interested in banalities.” You won’t find the soaring oratory of Tony Kushner’s AIDS patients and Tom Stoppard’s disillusioned intellectuals in her work; Baker’s characters speak softly, naturally, honestly.

A Q&A with Flavorwire (Sept. 2009):

FP: Who is your favorite playwright, and who has influenced you?

AB:If I had to choose a favorite it would have to be Chekhov. Other big influences include: William Shakespeare, Mac Wellman, Caryl Churchill, Vladimir Nabokov, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, Edward Albee, Thomas Mann, Jane Austen, Fritz Perls, Eric Rohmer, and my mother. I realize only half of those people are playwrights.

Another InDialogue piece with Carly Mensch from The Brooklyn Rail (May 2010):

BAKER: […] when I was in school I wrote a long super-pretentious paper on laughter and comedy! The paper was on Beckett’s Watt and why I thought it was a) the funniest novel of all time and b) also a kind of treatise on laughter itself. At one point in Watt a character says:

The bitter laugh laughs at that which is not good, it is the ethical laugh. The hollow laugh laughs at that which is not true, it is the intellectual laugh.But the mirthless laugh is the dianoetic laugh, down the snout—Haw!—so. It is the laugh of laughs, the risus purus, the laugh laughing at the laugh, the beholding, the saluting of the highest joke, in a word the laugh that laughs—silence please—at that which is unhappy.

Anyway, I just went crazy over this quote. I won’t get into all the reasons, but somehow this “laugh laughing at the laugh” described to me what exactly I think is so great about Beckett. I also became obsessed with this idea of the “highest joke,” which for me was the gap between reality and language, or the simultaneous lack thereof. Like the more you try to convey reality through language, the more it becomes clear that there is a reality that language cannot express. But at the same time, language is the only reality we know. And that to me is just this amazingly sweet and comic paradox. And then I realized that pretty much all my favorite comic plays and novels deal in some way with this paradox. The laughter produced by these works is not so much directed towards the characters as directed towards language itself, and its gorgeous artificiality and insufficiency. Most comedies these days just involve ethical and intellectual laughter, and I always find them unsatisfying. I can’t say that I’ve ever achieved the risus purus in my own work, but I am sort of always striving for it in my unhappy little way.

A preview of a revival of one of her early plays, Body Awareness, in The Washington Post (Sept. 2012):

Playwright Annie Baker, at 31 a sudden darling of the country’s new-play scene, is charmingly laid-back until you bring up a word that often characterizes her barbed, often comic dramas: “gentle.”

“I know – I know!” Baker says, her blue eyes flying open and her soft voice beginning to sound a little scandalized. […] “I am very interested in cruelty and suffering,” Baker says, mulling it over. “But you could say I’m interested in gently looking at cruelty.”

From Interview magazine, a joint Q&A with Baker and director Sam Gold about their production of Vanya (no date given but it would have to have been from somewhere around June 2012).

GOLD: We’ve not adapted the play to take place in a different time and place than the author intended. I think that our desire to do this play does not come from an angle, and I think perhaps the desire is [for us] to have an angle. We’ve been really [careful] about the way people talk about the play, because it really affects the audience if [they] come in with some kind of angle in their head about how why they’re here, why we did it, “This is ‘blank’ Uncle Vanya.” We’re both very controlling people, so it feels really scary that there can wind up being some kind of way that the audience perceives this, that didn’t come from us. I think the American theater tradition is fairly narrow in how it thinks about the act of translation of the old texts and their reproductions, there’s a lot of convention about how an old play allowed to be staged in a contemporary setting. I don’t know why productions of Chekhov plays often have a similar look or a similar approach, when the play is 100 years old and there should be a million different ways to approach it.

BAKER: I feel like, from my experience of seeing Chekhov plays, there’s either the 19th-century, corset version, spoken in pseudo-British accents, or there’s the “updating” of it where [the characters] live in Cleveland, in 1982. [Our production] is not in the 19th century, but it’s not-not in the 19th century, either. I didn’t update any of the references, my adaptation is very literal. I didn’t have to do anything to it; if you just literally translate exactly what [Chekhov] wrote, it sounds super contemporary.

GOLD: I think we’re trying to be evocative; we’re trying to pull everyone in the room and do as minimal a job of interpretation as possible, so the interpretation happens in the minds of the audience. People are wearing contemporary clothing [in our production], but the reason they’re wearing contemporary clothing is not because we’re setting it in contemporary America, it’s because to me, neutral is contemporary clothing. They are, from the comfort of the clothes they wear in real life, telling the story of Uncle Vanya and evoking in your imagination the world of the play. If you were going to sit around and read the play, you wouldn’t think about the period, you would focus on hearing the play.

A preview of the London premiere of Circle, Mirror, Transformation in the Financial Times (June 2013):

For starters, she’s not a fan of the New Naturalism tag. “We need different terms,” she says. “The old ones are outmoded. They were outmoded when Chekhov wrote The Seagull.”

Suddenly, she swerves off on a tangent. “I think avant-garde plays probably represent real life much more accurately than realistic plays. Although … , ” she doubles back on herself without pausing for breath, “those distinctions are so 19th-century and iffy anyway. I want to straddle that line. People do it in visual art all the time. Like, you can paint a figure and have it be a figure and incredibly strange. If you get really close to something, it looks really weird and when you step back it looks like a lily pond. All these ideas. I’m interested in exploring … ”

She stops. It looks odd in print – scattergun and meandering – but this is how we talk in reality and Baker’s characters do just the same. Her writing is attuned to the about-turns, malapropisms and verbal tics of everyday speech and she demands pauses, some lasting two or three minutes. The distinction between stage time and real time is obliterated.

Anton Chekhov

From a preview of his play, Longing, inspired by two Chekhov short-stories, novelist and screenwriter William Boyd explains his take on Chekhov’s loves:

Chekhov loved women and their company – and he clearly loved making love to them, as the number of his sexual liaisons demonstrates – but in all his relationships he began to cool and draw away, just as they were reaching a point of amatory heat that implied something more lasting and intense.

His most ardent affair, I believe, was with a young woman called Lika Mizinova. Mizinova was 19 when Chekhov met her in 1889 (he was 10 years older). She was a friend of his sister and a young schoolteacher who had dreams of becoming an opera singer. She was ash-blond, a chain-smoker, buxom and sexy and she and Chekhov had a rollercoaster on-off affair that endured almost 10 years before the Chekhovian chill became intolerable and the possibility of marriage retreated over the horizon. However, while it was on it was clearly both great fun and very passionate. Chekhov and Mizinova’s correspondence is copious and highly indiscreet.

There are 98 letters surviving from Mizinova to Chekhov and 67 in the other direction. The tone is candid and mocking, almost derisory, as they each have a go at the other, revealing the erotic subtext beneath the charged banter, as if the letters themselves were designed to provide some sort of sexual frisson. Mizinova wanted marriage, but eventually realised that, for Chekhov, lasting mutual happiness was either something he didn’t believe in or saw as too great a threat to his freedom. Too much would have to be given up. One recalls Suvorin again: “he’s spoilt”.

A photograph of Mizinova and Chekhov at the end of their protracted dalliance in 1897 shows that she has put on weight. She looks and leans towards him but Chekhov is almost visibly recoiling, his body-language eloquent – canted away from her, his eyes elsewhere, legs crossed, hands clasped tightly over his knee, his face almost pinched in its hardness, its refusal to yield.

The following quotes are from correspondence, essays collected in Memories of Chekhov: accounts of the write from his family friends and contemporaries (McFarland & Co. 2011).

The Chekhov Family (and friends) In front of Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya home, 1890. (Top row, left to right) Ivan, Alexander, Father; (second row) unknown friend, Lika Mizinova, Masha, Mother, Seryozha Kiselev; (bottom row) Misha, Anton.

From his brother Alexander Chekhov.

Our mother, Evgenia Yakovlevna, was different from our father. She was a soft and quiet woman. She had a poetic nature. By contrast to the father, who seemed very strict, her motherly care and tenderness were amazing. Later, Anton Pavlovich said very truly: I have inherited the talent from the father’s side, and the soul from the mother’s side.

Very few of the readers and admirers of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov know that, in his early boyhood, he worked at a very small, cheap general store, helping his father. His impressions of a carefree childhood were based on observations made from a distance. He never experienced these happy years, filled with joy and pleasant memories. He did not have a chance to play with is friends, or simply sit around. He did not have time to do this because he spent most of his free time at his father’s general store. Besides, his father had rules and prohibitions regarding everything. He could not run around because, as his father told him, ‘You will wear out your boots.’ He could not jump because ‘only street bums hop around.’ He could not play with other children because ‘your peers will teach you bad habits.’

From Maria (Masha) Chekhova (Anton’s only sister):

In 1877, my brother [Anton] visited us briefly [living in Moscow in poverty due to father’s bankruptcy]. Upon seeing our hardship, Anton returned to Taganrog and began sending us part of the money he earned from tutoring, even though he himself lived from hand to mouth. From his youth, Anton had a sensible and responsible attitude towards our family, and he supported us by any means possible. Immediately after graduating from high school, he moved to Moscow, entered the university and became the chief provider for our family.

From Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, co-founder of the Moscow Art Theater:

Three portraits of Chekhov stand lined up on my desk. These three photographs are from the three periods in the writer’s life.

Period one: Chekhov as ‘a promising author.’ Sometimes they are brief pieces published in humor magazines, and these he signs ‘A. Chekhonte.’ How many of these short pieces did he write? Many years later, after he had sold all of his worlds to a publisher and was selecting those worth publishing, he said, ‘I wrote about a thousand short stories in my youth.’

Eventually, Chekhov begins to write lengthier, more serious short stories. He likes being in society, but prefers listening to speaking. The public starts to refer to him in the terms of a talented writer, but no one has yet dubbed him a living classic.

The second period: Chekhov is accepted as ‘one of the most talented writers of our times.’ His compilation of short stories, In the Dusk, receives a very prestigious literary prize. He writes less but is received with warmth in any editor’s office. People discuss almost every new work by him. […] A respected writer from the older generation, D. Grigorovich, makes a very bold statement, saying, ‘You can put Chekhov’s works on the same shelf as those of Gogol. That is as far as I can go myself.’

The third portrait: Chekhov at the Moscow Art Theater. These days he writes much less. In the two or three pieces he produces each year, he has strict expectations of the quality of his writing. A monumental new feature in his work is that, despite being a realistic writer, he lets his characters make general philosophical statements about life, using wise thoughts and maxims included in his works.

That said, the most important change of this time is that Chekhov becomes a dramaturge (sic), a playwright, and begins to spend more and more time in the theater. His popularity grows daily, and for many readers he soon becomes one of the most popular writers in the country. Only one writer exists whose name is more eminent: Leo Tolstoy. —

From Isaac Altshuller, Chekhov’s personal physician in Yalta:

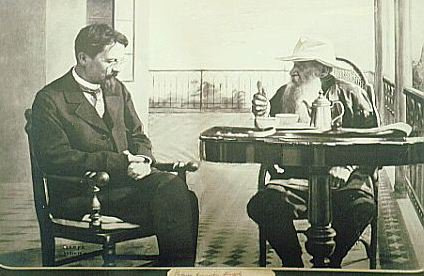

Chekhov liked Tolstoy very much. In 1901 Tolstoy was ill and living in Garspa, a small town near Yalta. Chekhov visited Tolstoy there on several occasions. Whenever Chekhov visited Tolstoy, the great novelist spoke to him in a very friendly and loving manner.

When I asked Tolstoy which of Chekhov’s books he loved the most, Tolstoy answered, ‘I live by Chekhov these days. I greatly admire and enjoy his works. He notices every little detail which is amazing. His works are filled with great messages, and he has developed his own style; he does not imitate anyone, but writes in his own way.’

After a while, Tolstoy added, ‘Chekhov is such a wonderful man, but his plays are simply terrible.’

From Grigory Rossolimo (doctor of neurology, chair of the University of Moscow’s neuropathology department in the 1910s):

After his graduation from medial school, he did not quit medicine, but worked as a country doctor. He treated his patients with great care and softness; he was a doctor, but first and foremost, he was human.

Upon graduation, Chekhov was unable to continue his postgraduate medical studies, but he still read professional journals from time to time. He dreamed of becoming a university teacher, and he told me about this one day; I liked his idea. I told him that in order to teach at the university, he would need to achieve the degree of Doctor of Medicine.

‘How can I get an advanced degree? Maybe they could give me one for my book Sakhalin Island?’ he asked me one day. [In this book, Chekhov chronicles his 1890 extended visit to Russian penal colonies in Siberia where he encountered prisoners, ex-prisoners, exiles and native populations living in confinement, poverty, stricken with disease and degredataion. He took three years to write the text which is part medical anthropology, part social analysis, part observational non-fiction.]

‘I think you are right. This should be easy,’ I told him.

As soon as he gave me his consent, I met with the dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Professor F. Klein. The meeting was a complete disaster. The dean’s eyes widened, he looked at me over his glasses, and without saying a word, he turned his back on me. I reported my failure to Chekhov, who laughed heartily. On that day, he stopped dreaming of becoming an academic ….

Photo from Oct. 2012 captioned by the photographer: “A guest cottage on the Melikhovo estate with wooden curved windows. A grand staircase and terrace with flagstaff on the upper level is where Chekhov completed his “Seagull” in 1895. In this ‘writer’s house’ Chekhov spent two hours a day to meet and cure peasants from neighbor villages and towns giving thousands of poor people free medical treatment. When a flag on the terrace was on, the peasants who were waiting his help could came in and get the treatment of all kinds of diseases.”

From Nina Drozdova, painter:

Everyone in Melikhovo worked hard. Chekhov worked a lot during the wintertime. He awoke very early, and had his visiting hours before morning tea. He was a doctor to the locals in the neighboring villages. After tea, he created new works with words, while Maria and I would be drawing and pairing, using children as our models. In Melikhovo no one had a single moment to spare. […] At 8pm we had dinner together. Anton Pavlovich would then return to his study, often working past midnight. No one would bother him at home, so he could work at his own pace and ease.

Anton Pavlovich loved to be outside. He always liked to observe the bird migration each spring and fall. He used to take a break while working, see a robin fly by, smile and invite us to come and take a look at the bird. He was happy looking at the clouds, the trees and birds. He was happy living so close to nature, and he was more inspired to create as a result.

From Vsevolod Meyerhold:

One of the actors remarked that it would be nice to have the singing of frogs, the clattering of grasshoppers, and the barking of dogs in the background of The Seagull. Anton Pavlovich asked him in an irritated voice, ‘Why would we need all this?’ The actor answered, ‘To make it more realistic.’

Chekhov smiled and after a short silence replied, ‘What do you mean by ‘realistic’? Theater is a form of art. Our painter Kramskoi, has a wonderful painting with striking faces in it. What if you were to cut off one of the painted noses, and replace it with a real, human nose? The nose would be real, but the painting would be spoiled by it.’

From Maria [Karmina-]Chitau, actress.

By the time The Seagull was performed on the stage of the Alexandrinsky Theater [also known as the Russian State Pushkin Academy Drama Theater in Saint Petersburg, Russia], several young dramaturges and writers, including Chekhov, understood the necessity of new forms of theatrical expression. However, the public, the theatergoers themselves, hadn’t an inkling about these new forms and ideas, which had yet to appear on stage.

Ivanov was the first play by Chekhov staged at our theater. The play was wonderfully performed, and it was an immense success. The actors were fantastic, and the audience loved every moment. However, Chekhov’s second play, The Seagull, was not so lucky, and its first night turned out to be a disaster, for a number of reasons.

Chekhov was supposed to arrive at the theater and read his new play (with comments) in the dressing rooms. He was late, and the actors milled around, chattering, whispering, and constantly checking the clock. Eventually, Mr. Karpov, the artistic director came out to speak to use. Chekhov had sent a telegram from Moscow saying he was unable to come to St. Petersburg. We had expected that the author would be present to explain to us how to perform the ‘new ideas’ in his play. Instead it was Mr. Karpov who presented the play, and then we began rehearsals.

I should also say a few words about the performance itself. Afterwards, many people spoke and wrote about the public’s reaction to this play. We had never heard so much booing. For as long as I remember, no other performance in the history of our theater had ever failed so completely. […] A few days later, during the second performance of the play, there was a magical change. There were numerous cheers of, ‘Bravo! Author, author!’ And yet, we performed it no better the second time around.”

From Konstantin Stanislavski:

That day was the first night of his play, Uncle Vanya. Chekhov sat at the back of the theater. It was a great success. The public cried, “Author, author!” repeatedly, and applauded for a long time.

Chekhov looked happy as well. He saw our complete theater set, with all the actors and all the costumes for the first time. During the intermissions, Chekhov came into my dressing room. He was silent for most of the time, and he made only one remark about Astrov:

‘He whistles all the time. Uncle Vanya is crying, but Astrov whistles.’ Later I tried but could not get any more information about how to perform the play from him.

‘How could this be?’ I asked myself. ‘This is a very sad play, so why does one of its major characters whistle?’ So in future performances I made an attempt to whistle on the scene. That was it! Astrov whistled because he was cynical, and he did not care about people and about life. However, he loved nature and grew trees.