Technological Umwelten

Author: David Hemminger

Introduction

In Jakob von Uexküll and Thomas Sebeok’s semiotic theories, the umwelt (German for “environment”) of an organism is that organism’s “self-centered world”, that organism’s model for its perceived surroundings and experiences (Sebeok). The interactions of different umwelten comprise a semiosphere. Uexküll and Sebeok theorize that since different organisms have unique backgrounds and experiences, they will each perceive the same external environment differently, resulting in their having unique umwelten.

In the modern era technology augments one’s perception of reality, acting as an extension to the senses. With the help of a television set, the humble Homo sapien can now see and hear from across the globe. He can follow global news in nearly real-time and even communicate with others anywhere in the world. In addition to sight and sound, he can even smell from these distances using digital scent technology.

With these expanded senses our experiences are now augmented by the digital to create technological umwelten, self-centered worlds both extended and shaped by the reach of technology. Smart phones now allow for people to remain connected to the rest of the digital world from anywhere with service, extending our vision and hearing across the globe. Google Glass has been augmenting vision even more literally, always a square of right in the upper right hand corner just an “Ok Glass” away. As an extension of our senses, however, technology acts as a lense through which we view the world. Different technologies or media will then act as slightly different lenses, providing different perceptions of the same reality. Thus we see that as the types of technology and media continue to diversify and expand, so do their corresponding technological umwelten.

Variance Within a Single Medium: The Internet

As the popularity of the internet has grown, so has the number of different ways to access it. Xkcd comic strip author Randall Munroe demonstrated some of the many different variables in experiencing the web in his comic strip Umwelt. While the strip may seem ordinary at first glance, it contains far more depth than it appears. In fact the strip seen by each viewer upon visiting the web page is only one among dozens of possible strips, and the fact that that particular strip appears is dependent upon variables such as the location of the computer’s IP address, the internet browser being used, the size of the computer screen being used, the page from which the comic was reached, and more. Different users end up having vastly different perceptions of the same web page, with differences between potential strips ranging from completely different content, to a single word being swapped, to a strip with all the same dialogue but with slight variations in width that dramatically affect the setting.

The comic strip serves to demonstrate just how varied web browsing experiences can be from user to user. Even if two individuals choose to view the same page, they will be viewing it through unique lenses. Different browsers can render the same HTML code in slightly different ways, and users can link to the page from many different places, with each place providing its own context for viewing the page. If two users are on distinct computers or operating systems, that will navigate the page differently, using keystrokes and hardware particular to their own machines. A browser app called Adblock is also changing the way users view websites.

Even more likely is that users will visit different pages altogether. With referring venues such as Facebook, Google, and Reddit personalizing their feeds and search results to individual users, giving thing disparate experiences right out of the gate. Technological umwelten are defined by what the user can potentially sense, and as more and more search engines, social sites, and news feeds personalize content, users will be introduced to personalized segments of the much larger web. Once they are placed into their unique segments of the internet, the browsing portions of users’ technological umwelten will necessarily be unique.

Even when large websites, internet tycoons that Jaron Lanier heralds as siren servers (Lanier), appear to dominate a particular niche, the internet remains diverse. As we can see from Munroe’s Map of Online Communities, the internet is divided into countless semiospheres, many of which are more or less unknown to each other. While Facebook may dominate the northern half of the map, it too is subdivided into many different communities. If there is room for both “Farmville” and “Happy Farm”, it is hard to imagine there being a niche on the social giant that does not already exist.

Variance Throughout Different Media

Technology is changing the world more generally than just the internet, however. The number of media through which a user can simply read a book is increasing at an exponential rate. Half a century ago the only option for reading a book was by obtaining a physical tome. Unless there were multiple print runs, all users would read near-identical copies of the printed pages, seeing the words through the common lense of the only available medium. Now a text can be read via book, audio book, e-reader, computer, cell phone, or any one of countless other platforms. The digital versions can come with annotations and are navigated differently with the aid of text search features. They may often be downloaded not only from the original source, but also from many secondary sources, both legitimate and illegitimate. Authors can, rather than creating errata, can directly modify their text and have all future downloads be changed, as if they were sneaking into the printing press during the middle of a run and swapping out keys. Hundreds of users can now read the same book, originally printed in the 1950s, each through a slightly different perspective.

With so many new ways to read a text, the effects of technology on the humanities are already noticeable. Works such as Robert Kendall’s “Candles for a Street Corner” take advantage of the ability to add sound, motion, and color to a text, giving users a new way to read a poem. In “Candles for a Street Corner”, Kendall takes a poem he has written, and, rather than publish it as a simple text, records himself reading it. Michele D’Auria then adds a graphic animation to complement the reading, complete with floating pieces of the text from the poem. The new medium changes how the poem is received. Not only does the reader hear Kendall’s choice of tone and emphasis when reading, but he also sees which graphics are chosen to emphasize and add to themes from the poem.

Sometimes in works in the digital humanities, the message is in the medium, as in the case of Eugenio Tisselli’s “Degenerative”. In this piece, Tisselli creates a web page that, each time it is viewed, randomly deletes or modifies a character. In a brilliant commentary on the two-way relationship between art and its viewers, “Degenerative” invites the reader to analyze not the content of the page (which is quickly randomized), but rather the process under which it goes and the medium through which it is displayed. It is a relatively new type of art, and rather powerful. In fact, the digital humanities as a whole serves as an example of how technology is diversifying the ways we can experience artistic works, one more aspect of technological umwelten that is unique from person to person.

Media Element: A Simple Example

In the media element of this project, we examine one sentence: “I didn’t say she stole my money”. While it may seem like an innocent sentence at first glance, it has achieved widespread internet popularity for having the special property that it takes on seven distinct meanings, depending on which word is stressed. In this projects media element we examine how viewing this sentence through different media can affect how the reader will likely assign emphasis to a particular word.

In its basic HTML, we see that the sentence appears with each word in a different color on a gray background. Different readers will likely stress different words when they read the sentence, likely depending on some combination of the colors of the words and their individual backgrounds. What’s interesting, however, is that when viewed through different media, the message of the sentence is changed. When we click the “animate” button, for example, we see that the word “say” is briefly printed much larger than the others, making it a natural choice for the word to be emphasized. While the colors and relative positions of the words have remained constant, the added dynamic of change over time allows for the word “say” to be emphasized in a way that it wasn’t before.

Notice, however, that if we look at the source code for the page, the reader is led towards a different interpretation for the sentence. The spacing and commenting contained within the code don’t appear when the page is created, but they both serve to emphasize the word “she”. When printed out in black and white, the page offers yet another interpretation. In doing so the reader sees that, rather than having a particular word be emphasized, the word “didn’t” vanishes into the gray background, making the sentence read “I say she stole my money”. In this case the conversion to black and white has resulted in enough data loss for the sentence to be fundamentally changed.

Hamlet in a Single Image: Another Example

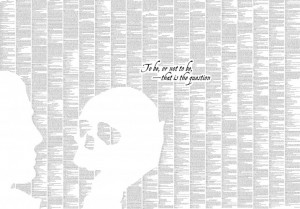

Another excellent example of how the presentation and interpretation of the same content can be so different across different media is this poster containing the entire text of Hamlet:

A book and an image offer quite different possibilities as media. A written text such as a book or play is good at conveying large amounts of information, while struggling to convey it’s main idea or message at a glance. An image, however, is in many ways the opposite — while it can’t convey hundreds of pages of text (at least not in the same way), it is good at immediately expressing broader themes. In this example, we see that while it is impossible to read the text in the poster, the important line “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” is brought to the forefront, while it would normally be hidden in the middle of the text. We also see that the poster is able to play with negative space in ways that the pages of a book don’t usually allow, creating a picture of Yorick’s skull.

A Look to the Future

A larger and larger portion of the global population has their senses augmented by technology every year. Technology then influences the way each one of them perceives the word. As we saw with our two previous examples, these new ways are not necessarily good or bad, but rather simply different. Furthermore, as technology continues to diversify with the creation of new media and extension of the old, the corresponding technological umwelten diversify as well.

Even as technological umwelten grow and become ever more intertwined, they become that much more diverse. Whether through choice of medium, digital community, or hardware, we are constantly creating for ourselves unique experiences and perceptions of one common world. The increased diversity is fueling the humanities and affecting every citizen of what is becoming a global community, and, most importantly, it doesn’t show signs of stopping any time soon.

Works Cited

Kendall, Robert. “Candles for a Street Corner.” . N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec 2013. .

Lanier, Jaron. Who Owns the Future. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013. Print.

Munroe, Randall. xkcd. N.p.. Web. 13 Dec 2013. .

“Personalized TV ads coming to your living room.” Chicago Breaking Business. N.p., 7 Mar 2011. Web. 13 Dec 2013. .

Sebeok, Thomas A. Contributions to the Doctrine of Signs. 5. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1976. Print.

Tisselli, Eugenio. “Degenerative.” . N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec 2013. .

Wachowski, Larry, writ. The Animatrix. Writ. Andy Wachowski. 2003. DVD. 13 Dec 2013.