Just like many other technological elements, video games act as a medium that are capable of portraying themes, emotions, lessons, judgments, truths, and many other factors that can teach us things about the world, ourselves, and others. In the introduction to How to Do Things with Videogames, Ian Bogot states, “We can understand the relevance of a medium by looking at the variety of things it does” (3), and games play a much larger role than just providing entertainment, whether we are aware of this or not. Games can be used as to train people—more emotionally and mentally than physically—for real life situations. Army soldiers play video games to prepare their reaction times and emotions for battle and astronauts utilize virtual reality for flight simulation. In both cases, the participants are able to undergo real life experiences minus the reality, thus ultimately removing the aspect of death. And it’s not to say that this doesn’t have an affect on their experiences, as there is a survival element within all of us that is activated in the presence of near-death situations. Yet, being able to prepare for the other emotional aspects tied into such scenarios can prove advantageous. But games don’t have to be “educational” to prove a point, and the point that they prove may not even be intentional.

I know from playing games I have experienced real-life emotions—such as an increase in heart rate, sweaty hands, an increase in concentration—in response to situations, regardless of whether or not those situations are considered “realistic”. In that moment, you are immersed in the game, you are the avatar, and it is that life that is your focus. But just because you are removed from reality doesn’t mean that you cannot learn from these “artificial experiences”. In fact, games provide a means for us to explore the world (or worlds) and experience perspectives that reality may inhibit us from perceiving. There are elements of a game, such as multiple dimensions or “power-ups”, which do not exist in our reality yet that still allow us to connect to the world in ways similar to how we would connect to our world, to aid us in challenges and direct how we approach problem solving. The study of games and reflection of ourselves—within the constraint of the rules of the game’s creator—could offer interesting insight into us as humans and the way we approach different situations and react to scenarios.

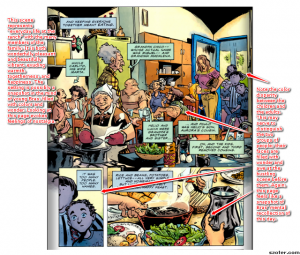

Games don’t have to be “life-like”, such as Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, or the Sims, all of which simulate real-life situations. I found that I learned more from the ones that removed me from the realism and placed me in a situation where I didn’t feel like I was in a game, or even experiencing it. Take for instance Storyteller, a relatively simple game that involves moving three characters around a fixed setting. The game seems simple, yet it became more interesting as you began to realize how moving the characters affected the ending. As I continued to play around with the characters, I began to see a pattern of which combinations would produce which endings. I had become a “god”, capable of manipulating the fate of the three characters. This is how the game became more than just a game; this is where it became a medium. It provides us with an interface through which we can examine our own morals and the consequences—without having to “actually” experience them. But just because it isn’t “real” doesn’t mean the game doesn’t invoke emotions. As I toyed with the characters, I realized that I was experiencing different emotional reactions to the different endings, and these reactions demonstrated how I perceive relationships and the subsequent actions that I took. Once you have created one story, and thus generated an ending, you can continue to manipulate the characters to change that ending. I found that the endings the included the death of one of the characters (usually marked by a blackened sky) made me go back and automatically try combinations that would reverse the black sky. However, in the relationships that ended with two of the characters alive (and with hearts and a blue sky), I was content and almost reluctant to change anything, regardless of whether the third character was dead or alive. These characters do not have names, do not have a back-story, are not portrayed as good or evil, and do not speak. I was judging them based on how I had placed them within the setting and on the resulting outcome, an outcome dictated by an algorithm. Though I was the “god” I was still confined to the rules of the game. It didn’t matter who they were or the intricate details that would play a role if they actually had “lives”. Yet I still cared about them, and sought to have a happy ending, even if that required the death of one. What does that say about me as a person? Am I that quick to judge, that quick to take sides? Am I that indifferent towards one life if it means the happiness of two others? These are all things I began to think about as I continued making combinations, and it was through the medium of this game that I was able to recognize these aspects of my self.

Storyteller is a simple game, a prototype even, and yet I was able to discover traits and think differently than I had before. If such a simple medium were able to provoke such an outcome, it would seem that the game as a medium holds truths and insights that go beyond beating an algorithm. You don’t just play a game, you experience it, and just as you learn from experiencing life, you learn from the game.

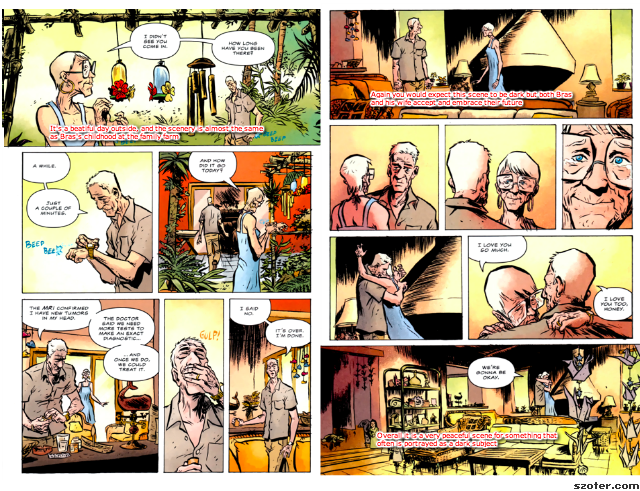

The same can be said for “The Company of Myself”, through which you learn the story of a lonely character’s life as you progress through levels. Each level begins with a quote from the character, aimed at giving you a hint for completing the level but also depicting the sad reality of the characters isolated life. The character is alone for most of the game until he falls in love with another character, Kathryn. For a few levels, you work with both of these players together, and through this you experience the bond between them as they help each other, and thus the gamer, progress to each level. However, at one point you are required to sacrifice Kathryn in order to complete the level. When I was playing, I experienced a sense of guilt for having been responsible for her death, yet conflicted because there was no other way to complete the level and continue going with the game. This guilt that I felt is shared by the character, as demonstrated through his quotes at the beginning of the levels. The game portrays a story in an interactive way that forces you to experience questions and sympathize with emotions in ways that another medium, such as a book or medium, could not. While those allow you to feel emotions and connect with the characters, you are detached from the story, whereas the video game element allows you to immerse yourself in the story, to be the one making the decisions–and it is that factor that affects how we perceive and reflect on the story we are given.

Games reflect elements of our lives and are models of our experiences, thus they will be different for each person who interacts with them. Games serve as a medium through which we can reflect on ourselves based on the reactions and decisions we make through game play. Life itself can be considered a game—both have goals, achievements, rules, challenges, and consequences and require contemplation of morals and values. When we play a game, we are playing a role with our actions, constrained by the rules of the game, yet free from the confines of death, as death is not as absolute in a game. But just because we have a reset button doesn’t mean we don’t treat a game as we would treat our own life.

Bogot, Ian. How to Do Things with Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Print.