Topic |

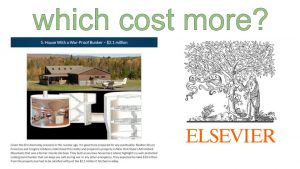

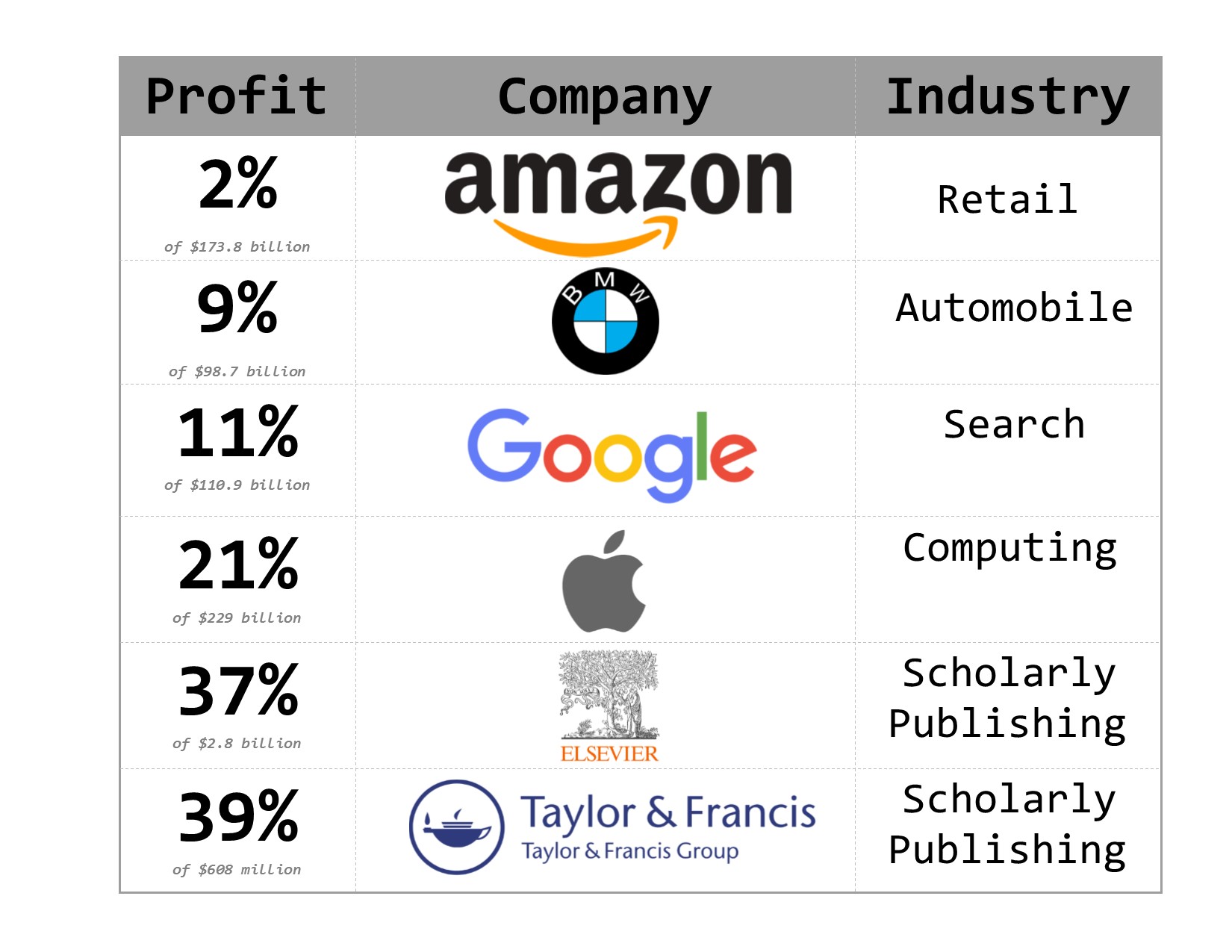

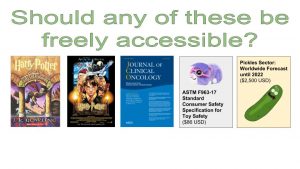

Paywalls and Information Costs |

|---|---|

| Key Takeaways |

|

|

Notes for the instructor/librarian

|

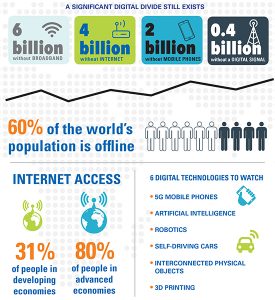

The topic of paywalls and information costs would be good for any intro-level student to learn about early on. Paywalls are a jarring reminder of the fact that access to scholarly publications is restricted and costs a lot of money. This topic may naturally inspire discussion of “information privilege” and the impact paywalls may have on researchers without institutional access. The issue of piracy (e.g., Sci-hub) might also come up and librarians and instructors should be prepared to discuss the ethics of this. |

| Lesson Content | Below you will find a variety of ways to briefly address this topic. Pick, choose, and adapt as you like. |

| Quick Mentions |

|

| Discussion Questions |

|

| Visuals & Media |

|

| Activities |

|

| Student Readings |

|

Category: Scholarly Communications

Journal Prestige

Topic |

Journal Prestige |

|---|---|

| Key Takeaways |

|

|

Notes for the instructor/librarian

|

This topic could fit well into instruction sessions that include significant treatment of source evaluation, and is one potential approach as you move beyond simple categorization of sources as scholarly/non-scholarly or primary/secondary. It stops short of a critical examination of construction of authority, but could be used to hint at greater subtlety and complexity. This topic has particular relevance for upper level undergraduates engaged in research, who may be starting to think about publication from an author’s perspective. |

| Lesson Content | Below you will find a variety of ways to briefly address this topic. Pick, choose, and adapt as you like. |

| Quick Mentions |

|

| Discussion Questions |

|

| Visuals & Media |

|

| Activities |

|

| Student Readings |

|

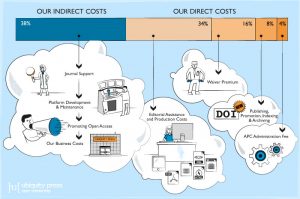

Subscriptions and Open Access

Topic |

Subscriptions and Open Access |

|---|---|

| Key Takeaways |

|

|

Notes for the instructor/librarian

|

This topic explores publishing business models, and may only be relevant for instruction sessions where the librarian is able to devote significant time to scholarly communication topics. It could be used as an extension to “sticker shock” topics, or possibly when discussing paywalls or information privilege. It might arise naturally in student discussion of those topics, and so could be useful to have considered in advance. |

| Lesson Content | Below you will find a variety of ways to briefly address this topic. Pick, choose, and adapt as you like. |

| Quick Mentions |

|

| Discussion Questions |

|

| Visuals & Media |

|

| Student Readings |

|

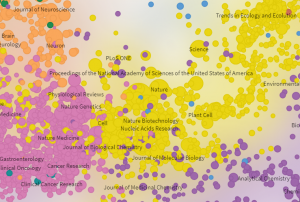

Scale of Scholarly Publishing

Topic |

Scale of Scholarly Publishing |

|---|---|

| Key Takeaways |

|

|

Notes for the instructor/librarian

|

Introducing this topic could be as simple as indicating the impressive number of scholarly articles published each year or size of library collections budgets, or be part of a lengthier lesson on how academic publishing works. It could be included in searching or source evaluation exercises, and may set the stage for understanding the fundamentals of scholarly communication. |

| Lesson Content | Below you will find a variety of ways to briefly address this topic. Pick, choose, and adapt as you like. |

| Quick Mentions |

|

| Discussion Questions |

|

| Visuals & Media |

|

| Student Readings |

|

Information Privilege

Topic |

Information Privilege |

|---|---|

| Key Takeaways |

|

|

Notes for the instructor/librarian

|

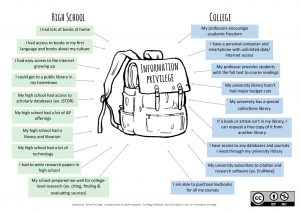

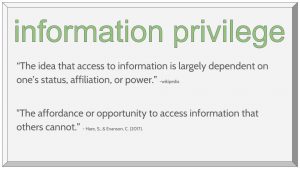

This topic could potentially be a touchy subject for students who haven’t thought about these aspects of privilege previously and should be framed carefully. It could be a great fit for an undergraduate course that has any social justice component. Students in these classes might be better primed for talking about disparities/inequalities and could apply that to this concept of information access. However, this discussion can be applicable to any level/discipline. |

| Lesson Content | Below you will find a variety of ways to briefly address this topic. Pick, choose, and adapt as you like. |

| Quick Mentions |

|

| Discussion Questions |

|

| Visuals & Media |

The “invisible knapsack” was introduced by Peggy McIntosh in a 1989 essay she wrote on “white privilege.” The essay describes what privilege (in this case, white privilege) looks like in everyday situations. This image riffs off of this and presents examples of what information privilege might look like. The image could spark a conversation for students about the privileges around info access they have experienced, but had not thought about.

|

| Activities |

|

| Student Readings |

|