Reading Virginia Woolf’s Hand: Revisions of “The Mark on the Wall” by Jessica N.

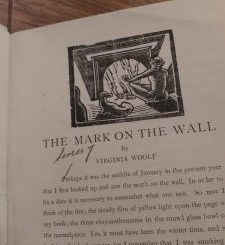

The object explored here, entitled Two Stories, is the first work Leonard and Virginia Woolf published themselves through Hogarth Press and includes Leonard’s “Three Jews” and Virginia’s “The Mark on the Wall” with four woodcut images by Dora Carrington. This edition contains an earlier version of “The Mark on the Wall,” and many of Virginia’s penciled-in corrections applied to the final version of the piece can actually be found in the margins.

Utilizing a stream of consciousness style, Virginia’s “The Mark on the Wall” begins with the narrator observing a mark on the wall and hypothesizing about what it could be. In these deliberations, the mind of this narrator tends to wander and she (or he) reflects on topics of knowledge, time, nature, and the like, turning back to discussing the mark whenever her thoughts become too unpleasant. At the end of the work, another voice in the room interrupts her thoughts and reveals the mark to be a snail. On the other hand, Leonard’s work in this object, “Three Jews,” represents an exploration of Judaism and contains the narrative of a Jewish father disowning his son after marrying a non-Jewish woman. The pairing of these two works truly emphasizes the novelty of Virginia’s style in “The Mark on the Wall.” When reading one after the other, the innovation of language, stream of consciousness style, and lack of defined plot all found in “The Mark on the Wall” become more pronounced when compared to the relatively simple, realistic narrative of Leonard’s “Three Jews.”

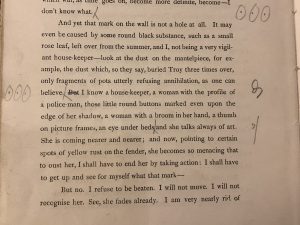

In addition to allowing the novel style of “The Mark on the Wall” to become more pronounced, this object also contains the corrections Virginia made to this piece before producing a final version. One of the most common corrections is changing a period into an ellipsis, which occurs 14 times in the print. This type of modification is particularly striking because it reveals the process of developing a stream of consciousness style and ultimately allows the work to more effectively mimic the thoughts of individuals. One example of this correction occurs on page 26 with the adjustment from the ending period in the phrase “an intoxicating sense of illegitimate freedom—if freedom exists.” to an ellipsis. Periods definitively end a sentence and tend to represent a more complete thought whereas ellipses indicate that the sentence or thought is unfinished. With this change from a period to an ellipsis, this sentence more clearly embodies the incomplete thoughts of a mind wandering as if entranced by the idea of true freedom, more effectively mimicking the process of consciousness.

Another notable correction is the removal of an entire passage discussing the housekeeper in detail, found at the bottom of page 22 into the top of page 23. In the version found in “Two Stories,” this passage begins with further description of the housekeeper as the narrator continues to explore her own consciousness, but then there is a moment of awareness halfway through; the narrator realizes that her mind is wandering, mentally forces the image of the housekeeper to leave her head, and completes her return to reality with a description of a tree tapping on a window. After the removal of this passage is put in place in the final version, the first mention of the housekeeper is included, but then the work jumps abruptly to this tapping of the tree. By eliminating this moment of awareness, the tapping of the tree functions as an interruption of the narrator’s thoughts instead of an observation after her thoughts have already shifted. This revision allows the reader to draw the conclusion of the separation of imagination and reality themselves instead of being explicitly told by the narrator. Deleting this passage then further demonstrates the process of exploring and perfecting the stream of consciousness style in this work.

The final page of “The Mark on the Wall” contains a print of Dora Carrington’s woodcut of a snail. The placement of the woodcut on the page discloses the fact that the mark is in fact a snail a page and a half before it is revealed in the text. Its inclusion seems surprising, given that the entire work centers around the contemplation of this mark. With this woodcut included in this printed version, it then becomes clear that what the mark turns out to be does not matter and is not the point of the story; rather, the main purpose is the exploration of consciousness, and the mark merely becomes a method for moving into, out of, and between musings.

This object is able to provide further insight into Virginia Woolf’s process and purpose for writing her short story “The Mark on the Wall” by exhibiting the context in which the piece was written, the corrections added before the final version, and the woodcuts selected to appear alongside the work.

Recent Comments