Not Just a Dream: La Guerre des Mondes Demands to be Taken Seriously by Alexandra K.

One of the things that was brought up in class about “A Dream of Armageddon” was how it seems less like speculative fiction because it’s in the context of a dream, and therefore easy to dismiss. To me, speculative fiction is defined as a prediction of what could come to happen in the future based off of the predicted trajectory of current events. “A Dream of Armageddon” is told from the perspective of a man on a train traveling in England, detailing his encounter with a fellow passenger who tells him about a dream of a war hundreds of years in the future, war planes and other terrible inventions that did not exist in 1901. By framing it within a dream, “A Dream of Armageddon” is neither speculative nor science fiction. In science fiction, the events are possible in the world defined within the story but impossible within the existing world. There is a distinct separation between these two worlds: based off of what we currently know to be true, things that occur in science fiction stories could not occur in our reality. In “A Dream off Armageddon,” the dream state seems to preclude the events theoretically occurring in the future, but also makes them not real within the story’s own world. We now know that similar events do, of course, take place, and the story is in fact eerily predictive of World War I, but at the time, it would have likely seemed like an outlandish idea.

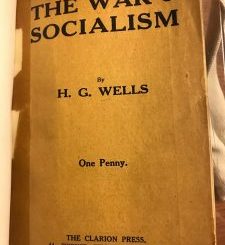

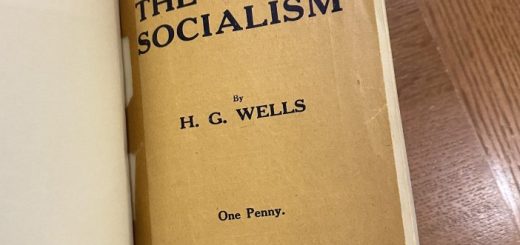

This in-between science and speculative fiction could easily have been a contemporary critique of the work as well, especially since the war planes would have been without precedent, and may have given it less power over readers. However, this copy of La Guerre des Mondes carries a certain gravity and suggests even if the short story was not taken as seriously by itself, it was likely still aided in its relevance by the novel’s success. While “A Dream of Armageddon” might not be classified as true science fiction, The War of the Worlds would be, without a doubt, and defines Wells as an author of science fiction. By connection, “A Dream of Armageddon” becomes relevant literature as well. (This does not mean, of course, that once a writer publishes one book in a certain genre, they are limited to that genre for all future works. But in this context, I would argue that because his following works could be categorized in the same genre, his original publication strengthens that categorization.) The predictions and commentary that Wells makes could be glossed over by focusing on the “dream” rather than the “Armageddon,” which would make the work much less powerful. However, The War of the Worlds is a full-length novel complete with world-building and an immersive experience for the reader, and was published before “A Dream of Armageddon.” It tells of Martians coming to England and waging war using other-worldly technology, not dissimilar from “A Dream of Armageddon.” In this context, it would be harder to view the short story as “just a dream,” when Wells has clearly put so much thought into the dystopian futures he creates. Both stories feature a very specific future threat that will change the world as we know it. Both have dark themes and darker stories and tell of a future where technology hurts us more than it helps us.

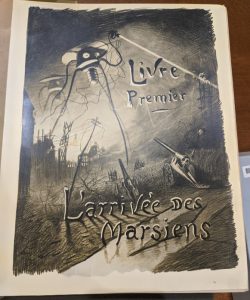

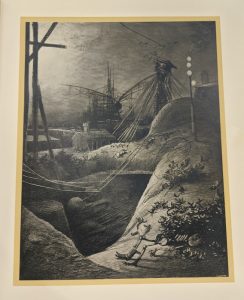

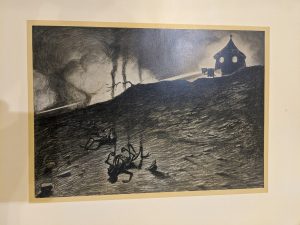

The format of this particular edition really adds to the dramatic effect that the novel carries. It is much larger than the average modern book, and while larger books were more common around the time of publication, smaller and cheaper books did exist. This lends to the presence and weight that the book holds – the physical copy itself has a literal and metaphorical gravity to it. It takes up much more space than a short story. It would be visible in a room, no matter where it was stored.

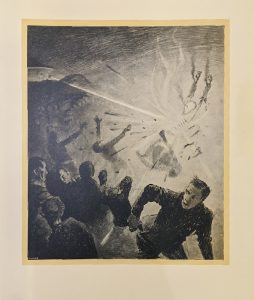

At approximately twenty inches tall and at least three inches thick, taking it out to read would have to be done with some thought – this is not a book one can casually pick up during tea. The book is not entirely leather bound but rather has a padded cover with a very thin covering of leather. (At least, I assume it’s leather, and its papery nature is due to time rather than composition.) It’s fragile and almost soft, not sturdy like a leather tome would be. It must be treated with care – displayed for posterity rather than used. The illustrations are dramatic, haunting, disturbing. They’re done in black and white, heavily shaded, and accompanied by key quotes from the moments they are illustrating. This one, for example, is captioned (rough translation, please excuse any errors): “Immediately, blasts of genuine flame, their brilliant flashes jumping from one to the other, burst from the scattered group of people. One could say that some invisible blast was beating against them and that a white flame was born from the collision. It seemed that each of them suddenly and momentarily became changed into flame.”

We see similar imagery in “A Dream of Armageddon,” but the imagery in La Guerre des Mondes seems more real, both due to its context in a longer work and the accompanying image. With a novel, you spend so much time with the characters that it’s easier to picture yourself seeing this brilliant flash. In contrast, with the short story, it was easier for me to separate myself from the things taking place – not only did the narrator not personally experience the events, but the person describing the war didn’t technically experience them either, just dreamed about them. This adds up to three degrees of separation – the book itself, the narrator, and the dream – instead of just one with The War of the Worlds.

This copy also reveals that this novel had a certain status granted to it, and may have been used as a marker of status. It has been translated into French from the original English, indicating its widespread readership. Furthermore, it is a unique translation – only 500 copies of this edition were produced, and they are each individually numbered and signed. This one in particular is “Exemplair Nº trente-cinq, appurtenant à…” The illustrations are incredibly detailed and on glossy paper. This all indicates that it was likely something of a collector’s item, suggesting that if you were to be considered a cultured, well-read person at the time, you simply must have read The War of the Worlds. To have this particular edition of it would signal your status, and it would be a prized possession due to its cultural influence. This, too, indicates that even if “A Dream of Armageddon” is just about a dream, it would probably have been tugged along with The War of the Worlds and been read as significant and culturally relevant. This copy of La Guerre des Mondes indicates just how well-known an author he was. I can imagine people reading this novel and then eagerly awaiting his next publication, looking forward to reading about more machines that are alien and impossible, reading about more devastating wars in which machinery plays a defining role. Coming off of the context of The War of the Worlds, “A Dream of Armageddon” becomes more serious than the first time I read it by itself. It’s more somber and holds a greater weight.

The War of the Worlds was powerful enough to earn a distinguished place in contemporary literature. I take anything that Wells has to say more seriously after that. It’s closer to home, too – aliens probably aren’t going to descend on us any time soon, but other humans might. By itself, “A Dream of Armageddon” is just a dream – a disturbing one, but just a dream. Next to La Guerre des Mondes, there’s a nagging feeling that Wells isn’t making this up completely – there’s something significant that both his works are saying, and it’s hard not to listen when a twenty-inch image is showing it to you.

Recent Comments