Hogarth Press’s Virginia Woolf, Haunted House and Other Stories by Margaret G.

I visited the Rare Books collection to see Virginia Woolf’s “A Haunted House & Other Stories” compiled post-humorously by her husband Leonard Woolf and published by the Hogarth Press in London, 1943. The object was smaller than I expected — my stretched-out hand almost reaching the full length of the laminated book. The pages were thick with brown, cardboard-like texture and some discoloration. What struck me most initially was the book jacket, designed by Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell. Bell was an artist and also a member of the Bloomsbury Group. I found her black and white flower print for the book cover adds to my understanding of why “A Haunted House” was chosen as the titular text. The flowers add a sense of familiarity and domesticity that appear in Woolf’s work; however, what always captivates me is how Woolf adds so many layers about social and personal identity, culture, and melancholy to what is on the surface of domesticity. In Bell’s cover image, some of the flowers have fallen off the bouquet and a checkered pattern with diagonal lines form the background. These themes of nature, confusion, and reflection constantly surfaced as I read through the book.

I visited the Rare Books collection to see Virginia Woolf’s “A Haunted House & Other Stories” compiled post-humorously by her husband Leonard Woolf and published by the Hogarth Press in London, 1943. The object was smaller than I expected — my stretched-out hand almost reaching the full length of the laminated book. The pages were thick with brown, cardboard-like texture and some discoloration. What struck me most initially was the book jacket, designed by Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell. Bell was an artist and also a member of the Bloomsbury Group. I found her black and white flower print for the book cover adds to my understanding of why “A Haunted House” was chosen as the titular text. The flowers add a sense of familiarity and domesticity that appear in Woolf’s work; however, what always captivates me is how Woolf adds so many layers about social and personal identity, culture, and melancholy to what is on the surface of domesticity. In Bell’s cover image, some of the flowers have fallen off the bouquet and a checkered pattern with diagonal lines form the background. These themes of nature, confusion, and reflection constantly surfaced as I read through the book.

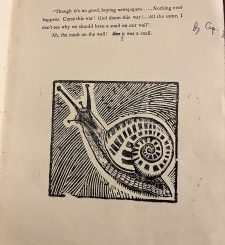

There were many more stories than I originally thought in this work. However, the three stories from the collection we read (“The Lady in the Looking-Glass: A Reflection”, “The Mark on the Wall”, and “A Haunted House”) have many threads in particular in common, and having them together in this collection made them seem more similar. “The Lady in the Looking-Glass: A Reflection” follows an unnamed narrator visiting the house of Isabella Tyson and observing her through a looking glass. “The Mark on the Wall” also contains the stark feeling of self-consciousness as a woman stares at a fire reflecting on her life and sees a snail, the mark on the wall. “A Haunted House” — a story of a ‘ghostly couple’ moving through a house looking for something — as well as the other stories in this collection point to social criticism and questions about identity. In “A Haunted House,” the two individuals in the story have this sense of heightened  awareness of self that is also present in other works such as “The Lady in the Looking-Glass” because of the theme of reflection. Amidst this awareness and reflection, in the haunted house environment, there is the theme of self-protection in the chaos and uncertainty of an ominous environment (both externally and in the characters’ minds). Yet, I noticed throughout the stories, Woolf returns to nature for acceptance of the unknowns of life and death. In another story in the collection, “A Summing Up,” Woolf writes of the soul, that it is “the conscious of a movement in her of some creature beating its way about her and trying to escape” (124). She echoes this sentiment in “The New Dress”: “We are all like flies trying to crawl over the edge of the saucer” (45). If philosophy is the striving to understand the truth about the intellect and poetry is the striving to dance with the intellect, Woolf is the genius at the intersection of the two. I realized from the three stories we read from her collection that Woolf crafts writing in a way that honors individual experience while revealing patterns of human nature.

awareness of self that is also present in other works such as “The Lady in the Looking-Glass” because of the theme of reflection. Amidst this awareness and reflection, in the haunted house environment, there is the theme of self-protection in the chaos and uncertainty of an ominous environment (both externally and in the characters’ minds). Yet, I noticed throughout the stories, Woolf returns to nature for acceptance of the unknowns of life and death. In another story in the collection, “A Summing Up,” Woolf writes of the soul, that it is “the conscious of a movement in her of some creature beating its way about her and trying to escape” (124). She echoes this sentiment in “The New Dress”: “We are all like flies trying to crawl over the edge of the saucer” (45). If philosophy is the striving to understand the truth about the intellect and poetry is the striving to dance with the intellect, Woolf is the genius at the intersection of the two. I realized from the three stories we read from her collection that Woolf crafts writing in a way that honors individual experience while revealing patterns of human nature.

The book itself was of a size and style that seemed very accessible to a common audience.  For instance, the cover and style of the book were not overly or ornately decorated. Bell’s print on the front presents a domestic scene of flowers in a vase with a style that reflects the theme of melancholy, particularly for women constrained under domestic and social culture. I could imagine any person picking this small book from a shelf in the library and finding something familiar inside. An interesting discovery was an advertisement in the back cover about Britain ‘calling the world’ — presumably, a radio station during World War II acting as “the voice of freedom.” As a 21st-century reader finding this object in the Duke Rubenstein Rare Books collection, I can only imagine what finding this book in the 1940s in the streets of London would mean to me.

For instance, the cover and style of the book were not overly or ornately decorated. Bell’s print on the front presents a domestic scene of flowers in a vase with a style that reflects the theme of melancholy, particularly for women constrained under domestic and social culture. I could imagine any person picking this small book from a shelf in the library and finding something familiar inside. An interesting discovery was an advertisement in the back cover about Britain ‘calling the world’ — presumably, a radio station during World War II acting as “the voice of freedom.” As a 21st-century reader finding this object in the Duke Rubenstein Rare Books collection, I can only imagine what finding this book in the 1940s in the streets of London would mean to me.

Recent Comments