Renée Vivien and the Creation of Women’s Spaces by Trina P.

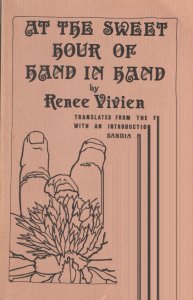

“At the Sweet Hour of Hand in Hand” is a poetry collection by Renée Vivien, a British poet who frequently wrote in French. The work itself is a modest and thin paperback of small dimensions, only 81 pages in length. The collection is a  translation from the original French and includes both an introduction and a short foreword. Vivien’s name and the title of the work, in a Baroque-style font, graces the front cover of the work, along with an illustration of hands clasping flowers.

translation from the original French and includes both an introduction and a short foreword. Vivien’s name and the title of the work, in a Baroque-style font, graces the front cover of the work, along with an illustration of hands clasping flowers.

Overall, the collection addresses themes such as love, identity, and womanhood. The collection focuses heavily on the romantic love of two women, primarily reflecting on the interior feelings of the individual women, as well as the relationship between two women as one romantic unit and the outside world. Vivien also frequently references the poet Sappho of Lesbos. Sappho was a lyrical poet from Greek antiquity, whose renowned works most often addressed romantic love between women and whose legacy birthed the terms “Sapphic” and “lesbian.” However, one of the most interesting aspects of Vivien’s work that I would like to address is the sense of innocence, youth, and naivety associated with the lesbian experience. Many of the poems in the collection refer to being a child, especially an ill one. One poem, in particular, titled “We Will Go to the Poets,” begins with this very idea. I have included an excerpt below for convenience:

“The shadows seem an enemy in ambush…

Come, I will carry you like a sick infant,

Like a plaintive child, sick and fearful.”

Mainstream heteronormative culture and media often lays out a “typical” timeline for certain experiences, romantic and sexual, that is usually not the reality for members of the queer community. Queer people oftentimes find themselves living their “true selves” much later in their lives, entering new and more genuine relationships after decades of heteronormative posturing with as much experience as a 15 year old going on a date for the first time! This common experience for the queer person, combined with the conventional idea of the woman as a caretaker, leads to Vivien’s frequent depiction of women as children in her work. For the women in Vivien’s work, uncovering and untangling one’s identity from the years of performance is not unlike creating one’s identity as a child. This lends itself well to our understanding of Vivien’s other work “Prince Charming.” The narrative here also begins with children, who in their youthful inexperience and indiscretions, are not given too much credit for their romantic interests or identities. The sister, Terka, described in this story as possessing “all the masculine faults” with wild, reddish-blonde hair, ultimately turns out to be the “Prince Charming” of the story. Furthermore, any queer sexual orientation is often reduced to just a “phase” or “experimentation” during childhood, even when it is clearly lifelong. In “Prince Charming,” Vivien combines all of these ideas into one work, introducing sexual orientation as a valid characteristic of one’s identity early on in life, emphasizing the gender binary (or lack thereof), and subverting the typical heteronormative narrative of “Prince Charming” to include those who are usually excluded.

Mainstream heteronormative culture and media often lays out a “typical” timeline for certain experiences, romantic and sexual, that is usually not the reality for members of the queer community. Queer people oftentimes find themselves living their “true selves” much later in their lives, entering new and more genuine relationships after decades of heteronormative posturing with as much experience as a 15 year old going on a date for the first time! This common experience for the queer person, combined with the conventional idea of the woman as a caretaker, leads to Vivien’s frequent depiction of women as children in her work. For the women in Vivien’s work, uncovering and untangling one’s identity from the years of performance is not unlike creating one’s identity as a child. This lends itself well to our understanding of Vivien’s other work “Prince Charming.” The narrative here also begins with children, who in their youthful inexperience and indiscretions, are not given too much credit for their romantic interests or identities. The sister, Terka, described in this story as possessing “all the masculine faults” with wild, reddish-blonde hair, ultimately turns out to be the “Prince Charming” of the story. Furthermore, any queer sexual orientation is often reduced to just a “phase” or “experimentation” during childhood, even when it is clearly lifelong. In “Prince Charming,” Vivien combines all of these ideas into one work, introducing sexual orientation as a valid characteristic of one’s identity early on in life, emphasizing the gender binary (or lack thereof), and subverting the typical heteronormative narrative of “Prince Charming” to include those who are usually excluded.

Finally, I found that many of these ideas are reflected in the size of the work itself. The collection is slight, taking up little physical space and easily going unnoticed on a bookshelf. Though there are, of course, other factors that may contribute to its size – such as the number of poems Vivien wanted to include, publication requirements, and economic and material restrictions – it seems fitting that the work is so small. Historically, and still now, women are expected to take up as little space as possible, with daintiness, obedience, and noiselessness extolled as the best characteristics of women. This is not to mention that a patriarchal society freely gives men spacious reign in all realms – physical, financial, academic, while confining women to the navigating the small spaces left in between. This effect is only magnified for lesbians, WLW, Sapphic women, and so on, who are further distanced from and indifferent to men. “At the Sweet Hour of Hand-in-Hand” is a strikingly fitting physical representation of how womanhood, and especially lesbianism, blooms despite its confines, since it is rarely given the space it deserves.

Recent Comments