“Silly rabbit, Trix are for kids!” (but these fairytales aren’t!) by Angelina F.

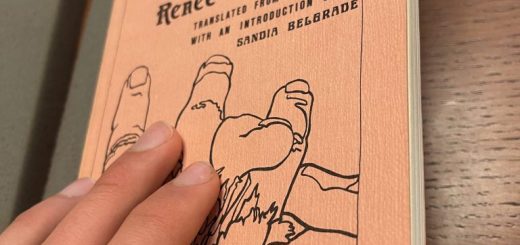

Note how small the book looked in my hands (and I have small hands). This increased delicacy only enhances the childlike nature of the stories.

The Happy Prince, and Other Fairy Stories was a small book with thick, pulpy pages. When I held it in my palm, I felt a flood of sentimentality rush through me, making the already delicate book feel all the more fragile in my hands. It was like I was a child again, eager to be told a story before I drifted off to sleep. Transported into a world of fantasy, I couldn’t help but enjoy getting lost in this cannon of fairy tales.

The question, “What is the significance of reading “The Nightingale and the Rose” in this collection rather than in a collection of short stories?” prodded me to consider what categorizes a work as a fairy tale in the first place. My initial thoughts resorted to the fantastical elements characteristic of many fairy tales, such as the presence of dragons and wizards, but this did not feel sufficient. What were the walls made of that segmented fairy tales off as a subset unique from other short stories? What niche does the fairytale fulfill that other types of short works otherwise might not? Fairy tales are typically geared toward children to teach them about the world around them, ironically through the creation of one far different from their own. Yet, however distant the faraway lands of these fairy tales may initially appear, the characters are faced with problems that mirror our own. They recount struggles of loss, of love, of conflict, of pain. The majestic aspects make the story more entertaining to the children while simultaneously making the abstract struggles that they will face in life more digestible and tangible. This alternate route provides them with an impactful and enjoyable way to reap valuable lessons. In other words, the fairy tale often has an alternative motive to pass on wisdom, a characteristic not required of all short stories.

Accordingly, Wilde’s collection of fairy tales follows this template of divulging insights to the

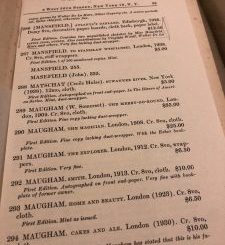

The delicate gold detailing, intricate and lovely, echoed the majestic, whimsical content of the fairy tales.

reader in each story. “The Nightingale and the Rose” recounts a tragic tale of nightingale in love with a young boy who is infatuated with someone else himself. The nightingale sacrifices her life in order for the boy to acquire a red rose, the object he seeks to win the affections of his love interest. However, despite the nightingale’s martyrdom, her sacrifice is one that is perhaps taken in vein as the boy’s love interest ends up rejecting him nonetheless, leaving the boy alone and the nightingale dead for a cause that never led to fruition. Reading “The Nightingale and the Rose,” amidst other fairy tales rather than simply among other short stories amplified my sensitivity to learn and gain wisdom from it as I was primed to look for a moral of the story. Thus, while I was still moved by the story the first time I read it on my computer screen, reading it the second time on yellowed pages rather than in the blue glow of my laptop was a far more impactful experience. In the context of other fairy tales, far clearer to me was the story’s warning of how blinding materialism and lust can be (even in the presence of true sacrificial love) and the harm that can come from excessive altruism.

Although the daintiness of the book may echo the sentiment that fairy tales are for children, Wilde proves capable of molding the genre for a more mature audience. He tactfully employs an understated approach by utilizing satire to present the moral of each story. Whether this takes the form of the excessively altruistic nightingale tragically immolating herself only to die in vain, the town council people selfishly jockeying for their own statues without knowing the sacrifices made by the Happy Prince, or the Young King’s subjects not respecting his rejection of luxury, Wilde humiliates society by unveiling its ugliness. Without sacrificing the childlike suspension of reality typically seen in fairytales (such as the use of talking animals in Starkid, for example), Wilde forces readers to face difficult truths about humanity aimed toward the receptiveness of an older audience. In “The Young Prince,” for example, the weaver states “In  war, the strong make slaves of the weak, and in peace the rich make slaves of the poor.” This profound statement is both quite complex, as well as draws a rather desolate perspective on the world, rearing this story less suitable for children. Furthermore, higher level allusions likely foreign to younger minds (such as references to Caine and Abel) and graphic details (that get somewhat gory) further this work to be suited for more mature audiences.

war, the strong make slaves of the weak, and in peace the rich make slaves of the poor.” This profound statement is both quite complex, as well as draws a rather desolate perspective on the world, rearing this story less suitable for children. Furthermore, higher level allusions likely foreign to younger minds (such as references to Caine and Abel) and graphic details (that get somewhat gory) further this work to be suited for more mature audiences.

Following the natural trajectory of growing up, the stories that have filled my shelves of late look far different from the Princess and the Pea. Reading The Happy Prince, and Other Fairy Stories, however, allowed me to revisit a fantastical genre I thought had been packed away with my baby blanket and stuffed teddies. I had not anticipated this small red book to steal my heart, transforming into a portal to the world of adult fairytales.

Recent Comments