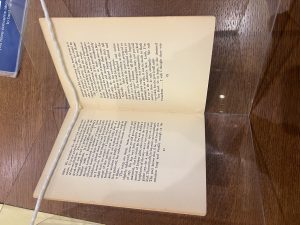

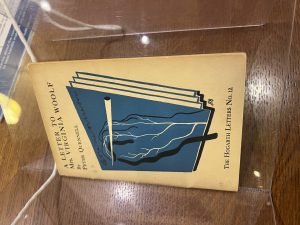

“A Letter to Mrs. Virginia Woolf” was written by Peter Quennell and published in 1932 by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s publishing agency in London. In its current state, the letter is small and yellowing, and the only colored ink utilized is an exquisite blue on the front page that depicts a hand as it writes in a book. The letter was the last in a series of twelve letters published by Hogarth Press and is evidently Peter Quennell’s response to an earlier correspondence sent by Virginia Woolf where she complained about her distaste for an up and coming poet. Quennell, who was Woolf’s junior by more than twenty years, was an English poet and biographer, and his response to Woolf’s criticisms reads much like a poem itself.

Quennell writes at the beginning about the man in question, “His poems strike your ear as tuneless and dull, yet you prefer to think of him not as simply a bad writer but as a victim of contemporary circumstance.” What struck me as odd about this sentence is the hypocrisy of Woolf lamenting about this poet’s “contemporary” writing style when she herself was one of the most prominent writers in the modernist movement in literature. Quennell then explains Woolf’s stance in greater detail, writing that she wishes the poet would refer to a “less self-conscious mode of feeling” and stop the “dogged effort” that he makes to “freshen up his use of the English language.” In these moments, Woolf seems to be complaining about the very style in which she writes, one that is characterized by experiments in language, attention to the subconscious, and a unique sense of time. This attention to the subconscious is particularly evident in “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street,” which is a short story written from the perspective of Clarissa Dalloway that uses a stream of consciousness writing style to describe feelings and memories evoked in her as she perceives the people and things around her. Furthermore, “A Haunted House” employs a similar stream of consciousness style that follows the most intimate thoughts of both a living couple, as they discover that there are ghosts in their house, and a ghost couple, as they search for a hidden treasure.

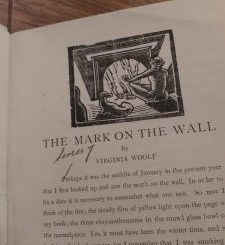

Perhaps the most hypocritical criticism of writing at the time by both Quennell and Woolf, though, is that the twentieth century poetry “represents a frenzied effort to gain time, mere ‘business’ till the fire begins to kindle.” In a period when technology and consumerism were rapidly developing, Virginia Woolf was obsessed with the passage of time and the “extraordinary discrepancy between time on the clock and time in the mind.” This obsession with time is reflected in many of her stories, including “The Mark on the Wall.” In this story, there is no true timeline from start to end as the narrator sits in her living room staring at a black mark on the wall. The story could have gone on over the course of two days or two minutes, but this distinction is left up to the interpretation of the reader. Time is not completely insignificant, though, and is weaved into the narrative through a series of flashbacks and images that the narrator ponders as she runs through the different possibilities of what the mark on the wall could be. Additionally, Woolf talks about the passage of time more explicitly in this story when she writes, “Why, if one wants to compare life to anything, one must liken it to being blown through the Tube at fifty miles an hour—landing at the other end without a single hairpin in one’s hair!” (Woolf 78) At this moment, Woolf exhibits her obsession with how time feels in different moments by likening the span of life to a mere Tube ride that is over before you know it, which again argues for the “short” story to span over a rather “long” period of time. The whole story is written in a dream-like, timeless state until the very end when the narrator is brought back to reality after someone mentions that the mark on the wall is really just a snail. In this way, “The Mark on the Wall” is the exact embodiment of that which Woolf claims to be the downfall of literature.

After reading this letter, I am left with a feeling of confusion more than anything else. The letter does not seem to be written in a sarcastic tone, which leaves me questioning how Woolf viewed her own writing. Was the sense of timelessness in her stories unintentional, or did she simply find her use of literary techniques to be more refined and nuanced? Moreover, at one point in the letter Quennell references their own “older critics,” which leaves me wondering what these critics had to say about Woolf’s work. Did they recognize and critique the same techniques in Woolf’s writing that she does in others?

Recent Comments