“The Happy Prince, and other Fairy Stories”: Wilde’s way to ward away true love by Ishaan M.

The object I looked at, “The Happy Prince, and other Fairy Stories,” featured “The Nightingale and the Rose” in addition to four other short stories: “The Happy Prince”, “The Selfish Giant”, “The Young King”, and “The Star Child.” When one thinks of “fairy stories,” a wide variety of things might come to mind: fantastical creatures, a dramatic adventure, lessons to be learned, but quite often, a happy ending. “The Nightingale and the Rose” unfortunately has no such finale; the rose born from the nightingale’s life blood is tossed aside to the street after the boy refutes “true love” after he and his rose are casually rejected by the girl whom the rose was conceived for. Interestingly, many of the other short stories in the book hold similar themes as “The Nightingale and the Rose” but contain a much lighter note and happier ending, offering a contrasting opinion of the lessons and values that Wilde aims to impart on an audience of children.

In “The Happy Prince,” the eponymous statue hopes to share the expensive and beautiful pieces that adorn it to the poor, in hopes that they will find better use for it. A swallow helps carry the jewels away, but eventually dies due to the severe cold, leaving the statue heartbroken and eventually taken down and melted due to its poor quality. The swallow and the nightingale have many parallels – both try to do a good deed to help another, but lose their life in the process and don’t fulfill the purpose they intended to serve. However, the lasting impact of death between the two stories is very different: the swallow and prince are both taken to heaven after their death and live in paradise with God, whereas the nightingale’s death takes on a far more sorrowful and seemingly meaningless purpose. The nearly identical reasons but differing results of the selflessness suggest that Wilde wished to impart greater emphasis on helping the needy rather than finding true love. The casual response of the student to love in the ending – he describes it as quite silly and impractical before choosing to focus on his studies – seems to further reinforce Wilde’s perspective of love as being not quite worth it.

“The Young King” also shares similarities with “The Happy Prince” and “The Nightingale and the Rose” with its portrayal of sacrifice. The young to-be king is horrified to learn of how the gems and valuables that he has obsessed over were actually retrieved – from the death of slaves, the weavings of pale and thin subjects, and miners killed by three plagues. Faced with his horror, he refuses to touch the scepter or crown, and upon nobles confronting him with the intent to kill someone “unworthy,” pearl white lilies and ruby red roses grow on him. Instead of the sacrifice of an animal like the other two stories, this short story by Wilde draws light to the sacrifice humans endure to produce beautiful items. Once the King adamantly refuses to touch items of death, even faced with his own death, he is touched by God. “The Selfish Giant” shares a similar view on death with “The Happy Prince,” yet it concludes with a more positive ending for the giant’s tale; the giant is old and weak but finally sees children playing outside in his garden. The giant then sees the child of Christ he had helped before, who then takes him to the same paradise of God the swallow and prince entered upon their death.

The presence of a divine being rewarding selflessness and sacrifice – often involving an animal or nature – seems to be more common in Wilde’s other short stories, but absent in “The Nightingale and the Rose,” making it stick out in this collection. There is no happy ending for the dead nightingale after it sacrificed itself for what it believed was true love – and ended up a failure – but there were far happier outcomes for the main characters whose purposes for sacrifice were different: helping the poor, standing with those of the lower classes and slaves who had been mistreated and killed, or creating happiness for children. It seems plausible that the demotion of sacrifice for true love in comparison to the other themes in this collection of short stories could be related to Wilde’s personal views of love, as he was involved in several scandals regarding his sexuality and had a rocky relationship with his wife and family.

The collection’s format further supports the idea that these stories are for children to learn about God, sympathy, and kindness. The work is small and delicate – an adult would have a harder time flipping through its pages but it would be perfect for a child. The title of “Fairy stories” seems particularly appealing to children, and though it does not have any colors or pictures characteristic of my children’s fairy tales, the stories all include fantastical elements such as giants and talking animals, along with main characters that are younger – such as the young boy in “The Nightingale and the Rose” or the prince in “The Young King” – and more connected to an audience of children. Yet, certain themes, specifically that of death and pain which are present in nearly every story, could make the stories suitable for an older population as well. The commonality of God in a majority of these stories suggests that Wilde also intended for this collection to teach children about Christian values and morals, such as kindness and sympathy, which lead to a connection with divinity and heaven in the stories, but perhaps less so about true love which is associated with just death.

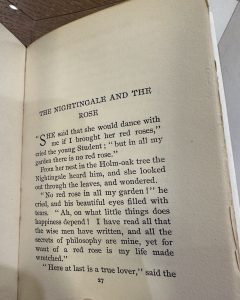

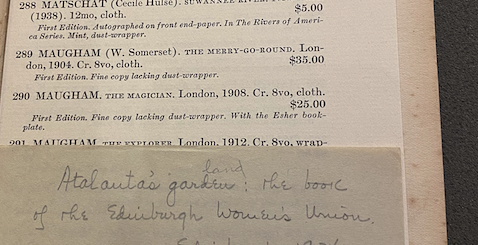

Below, I provide two pictures: first, the titles of the other stories in this collection, second, the first page of the Nightingale story which shows its small size.

Recent Comments