Wilde in America: Windsor Press and “The Nightingale and the Rose” by Anneke Zegers

Past Readers:

This rare copy of “The Nightingale and the Rose” (object PR5818 .N5 1927 c.1) by Oscar Wilde is a special edition published in 1927 by Windsor Press in San Francisco. This edition was published by itself, not in a collection with other short stories. It has no foreword, dedication, or endnotes remarking on the content of the story. Without any supplemental information or criticism, the story stands alone and must do the work of speaking for itself. The publishers may have intended “The Nightingale and the Rose” more as a novelty of a story than a piece of serious or scholarly fiction. It could be equated to a children’s book or a fairy tale in its presentation. Thematically this makes sense; Wilde’s story has many of the same tropes and magical elements as classic folklore.

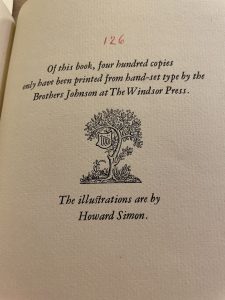

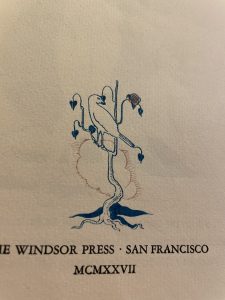

While this edition was published in the United States, it keeps the British spelling throughout, including on words such as “coloured” and “centre.” In the later pages of the book, there is a disclaimer reading “Of this book, four hundred copies only have been printed from hand-set type by the Brothers Johnson at The Windsor Press.” There is also a handwritten number, 126, marking which copy it was out of the four hundred produced. This is apparently standard practice for Windsor Press; on Ebay, I found a 1926 copy of “The Letter of Columbus to Luis de Santangel Concerning his Voyage to the Indies” which was also numbered by hand in red ink (compare above, with Wilde’s piece on the right). Note that the same Windsor Press emblem appears in both editions. However, the font is different between the two pieces. This might have been a stylistic choice on the part of the press. On the other hand, it also might have come from them updating their type script between the 1926 and 1927 publications.

While this edition was published in the United States, it keeps the British spelling throughout, including on words such as “coloured” and “centre.” In the later pages of the book, there is a disclaimer reading “Of this book, four hundred copies only have been printed from hand-set type by the Brothers Johnson at The Windsor Press.” There is also a handwritten number, 126, marking which copy it was out of the four hundred produced. This is apparently standard practice for Windsor Press; on Ebay, I found a 1926 copy of “The Letter of Columbus to Luis de Santangel Concerning his Voyage to the Indies” which was also numbered by hand in red ink (compare above, with Wilde’s piece on the right). Note that the same Windsor Press emblem appears in both editions. However, the font is different between the two pieces. This might have been a stylistic choice on the part of the press. On the other hand, it also might have come from them updating their type script between the 1926 and 1927 publications.

This edition of “The Nightingale and the Rose” is small and light, making it easily portable. It is 5.5 inches wide, 7.5 inches tall, and approximately 1 centimeter thick. I would guess that it has been taken several places and has passed hands more than once. Evidence of this comes from the book’s condition. It is in good shape, but the spine shows significant wear at the top; the heather green cover has peeled away in places to reveal the cardboard colored binding underneath. In addition, there is a dark black mark on the front cover and a few smudges on the pages throughout.

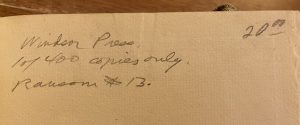

The most obvious evidence of its passage between owners, however, is the handwritten labelling on one of the early pages. The inscription includes the name of Windsor Press, the number of copies printed, and what appears to be the name “Rausom” with “#13.” It also gives the price of the book, labeled 20.00 (presumably dollars), in the top right corner. All of these details suggest that this copy once appeared in a book sale. The press name and circulation of the book would be important details for the seller to include in order to indicate the edition’s worth. “Rausom” may be the last name of the seller (it is also possible that I just cannot read the handwriting correctly, and this may say something completely different; when I first glanced at the cursive, I thought it said “rareroom”). The price shows how much the book went for at one point in its life. Its value has certainly increased since then. There is no indication of when the handwritten inscription was added or when the sale occurred. Together, the price and the damage to the copy suggest that this rare copy of “The Nightingale and the Rose” was not originally a keepsake or collector’s item. It was more of a casual reading; it passed hands between owners before settling in a library book collection. This edition reveals the process by which texts from famous authors could be made accessible to the American public for a relatively cheap price. I say relatively cheap since $20 is cheap for a book today, but I am not sure how inflation affects the pricing. Nevertheless, the fact that this book was mass produced in America shows an interest in British authors and an effort to make their writings—both short and long—accessible to the public.

The Rose:

The cover shows the dark silhouette of the titular rose. It is a simple design embellished with two silver stars by the rose’s stem. The title of the story is also in silver lettering, curing around the top of the rose. The choice not to show the rose in high detail is interesting. It may be that it was difficult to produce the cover art of the rose at the time of publication. On the other hand, the choice of the black-outline reflects that the rose was grown under the cover of darkness. The inclusion of the stars in the design around it supports this reading. Perhaps it also reflects on the tragic fate of the rose itself; the rose will be cast aside by both the professor’s daughter and the student, neither of whom know that it cost the Nightingale’s life. Neither of them see the rose in high relief or appreciate it fully; likewise, the reader cannot view the rose in all its glory.

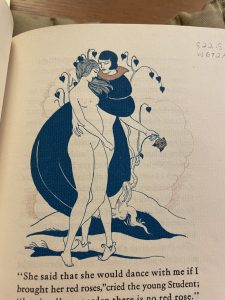

Besides the cover and the publisher’s insignia, there are two wood-cut illustrations printed in this edition. They are the work of Howard Simon (1902-1979). Simon was an illustrator, painter, and printmaker. He produced many of his illustrations, including these, by woodcutting. He was recognized as a member of the California Society of Etchers, and his works appear in major collections such as the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. For more on Howard Simon: http://www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/simon_howard_courtyardatrouen.htm.

Both illustrations appear at the beginning of the book; the nightingale is depicted on the title page, and the picture of the idealized lovers occurs just above the opening sentence of the story.

Both illustrations appear at the beginning of the book; the nightingale is depicted on the title page, and the picture of the idealized lovers occurs just above the opening sentence of the story.

The Nightingale appears in the rose tree. The red rose grows visibly on the bough behind it. The thorn piercing the moribund bird’s breast appears barely visible, jutting out near the base of the leaf near the Nightingale’s stomach. The tree appears remarkably small compared with what I imagined. To me, Simon’s interpretation looks like more of a shrub or bush than a rose tree. Furthermore, Simon took some liberties with the red rose tree’s placement. It ought to be beneath the window of the Student. However, this tree appears to have a cloudy sky in the background behind it, rather than a window or a wall. Simon seems to have taken some artistic liberties with his presentation of the story. Nevertheless, the general symbolism is correct. The two most important elements of the image, the Nightingale and the rose, are presented clearly. They also draw the eye’s immediate attention, the bird by its size and the flower by its burst of red in a largely dark blue sketch.

The second image is even more interesting. It appears just above the lines “She said that she would dance with me if I brought her red roses,” cried the young Student; “but in all my garden there is no red rose.” The picture shows the student in academic garb. His scholarly cape sweeps and flows behind his and his lover’s body. The young lady is naked in the image. She is without shoes, while the student’s feet have shoes like those of a court jester. The student’s right hand is low upon her waist and his left hand clutches the rose. Her eyes appear downcast, perhaps directed towards the rose she so desires. The tree and cloud behind the couple appear to be the same ones from the first sketch of the Nightingale; while both the tree and cloud are bigger in this image—the tree is certainly taller and fuller with leaves—these background details share the same coloring and style with those from the previous image.

The second image is even more interesting. It appears just above the lines “She said that she would dance with me if I brought her red roses,” cried the young Student; “but in all my garden there is no red rose.” The picture shows the student in academic garb. His scholarly cape sweeps and flows behind his and his lover’s body. The young lady is naked in the image. She is without shoes, while the student’s feet have shoes like those of a court jester. The student’s right hand is low upon her waist and his left hand clutches the rose. Her eyes appear downcast, perhaps directed towards the rose she so desires. The tree and cloud behind the couple appear to be the same ones from the first sketch of the Nightingale; while both the tree and cloud are bigger in this image—the tree is certainly taller and fuller with leaves—these background details share the same coloring and style with those from the previous image.

I believe that Simon shows in this later image what the Student was hoping his interaction with the young lady would look like. He imagines her naked, although this is not realistic in the cold of autumn or winter. He imagines a paradisal world with a tree full of leaves and life. He also imagines that she truly desires his rose, though this is proven not to be the case in the end. This image corresponds with no particular scene from the story. Rather, it shows what the story could have been and what the student aspires for his life to be. This is the ideal world where the lovers are happy and the Nightingale’s sacrifice receives the honor it is due. Better yet, this might be a dream vision of a world where the Nightingale did not need to sacrifice herself; in the world of this image, a red rose may grow in winter without the sacrifice of a pure-hearted nightingale.

Formatting and the Text:

There are a few notable formatting differences between the edition we read in class (Oxford World Classics) and the Windsor Press edition of “The Nightingale and the Rose.” First of all, the paragraphs of this edition are not indented. It is not always clear where one paragraph stops and the next begins. The Windsor text is therefore more free-flowing, while the OWC breaks the author’s ideas apart more distinctively. The choice not to indent may have been made only for the sake of economic printing. Nevertheless, it influences how the text appears on the page and how one sentence leads into the next. It is also noticeable that the OWC edition uses single quotation marks for dialogue, while the Windsor text uses double marks (e.g. ‘The Prince gives a ball to-morrow night’ vs. “The Prince gives a ball to-morrow night”). Furthermore, these editions have their page breaks at different lines and places in the story; these inadvertently create different moments of suspense and wonder as the reader changes from one page to the next.

The text itself also has some inconsistencies between the two versions. I have made a chart of the differences I observed:

| Oxford World Classics Edition | Windsor Press Edition |

| ocean-cavern (p. 81) | ocean cavern |

| ‘One red rose is all I want,’ cried the Nightingale, ‘only one red rose! Is there no way by which I can get it?’ (p. 81) | “One red rose is all I want,” cried the Nightingale. “Only one red rose! Is there any way by which I can get it?” |

| But the Oak-tree… (p. 81) | But the oak-tree…

(In the second use of “oak-tree” a few lines later, the O is capitalized). |

| ‘that cannot be denied to her…’ (p. 82) | “that cannot be denied her…” |

| petal following petal, as song followed song

(p. 82) |

petal followed petal, as song followed song |

While most of these inconsistencies barely affect their sentences’ meanings, a few of them alter the emotional impact, sound, or appearance of the text. For example, “Is there no way by which I can get it?” and “Is there any way by which I can get it?” have vastly different emotional impacts. The word “no” conveys a greater sense of hopelessness and futility; it suggests the impossibility of finding a red rose. Meanwhile, “any” sounds like there is a way to find such a rose, the student only does not know it yet. While the latter instance is true to the events of the story (the nightingale sacrifices its life to produce the red rose, showing that it is possible to find such a flower), the student’s lament makes more sense to express the dejection he feels in that moment. Furthermore, the futility contained in the phrase “no way” agrees better with the end of the short story, as the Nightingale’s sacrifice proves vain.

Oxford World Classics is a highly reliable source of literature; its editors typically consult multiple versions of a text to find the most original. They also tend to use footnotes to mark where the text has mutated over time. For this reason, I am inclined to favor the OWC as the edition more true to Wilde’s original vision. Therefore, the differences between these editions, although small, show how mistakes can appear in a text over time as it is copied and transmitted to a new audience. Perhaps the typist at Windsor Press made some errors in setting the type, since the type was set by hand. On the other hand, the Windsor Press edition may have been using a source copy of the story which already possessed these subtle changes. These minor, yet interesting variations—such as the difference between “following” and “followed”—speak to a history of book printing which is not without its accidental “revisions” to established stories.

Recent Comments