The Role of Art in Overcoming Nihilism in Society – An Examination of Albert Camus’ Nobel Acceptance Speech and the Short Story “The Adulterous Woman,” by Angikar Ghosal

Albert Camus received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. The English translation of his Nobel acceptance speech was published in 1958 by Knopf. This publication is a very thin paperback booklet of only 14 pages and resembles an artefact or a memento. The speech published contains Camus’ musings on the nature of art itself, his relationship with his audience and his readers, the role of the artist in the sociopolitical climate he received the prize in, as well as how historical events has affected his generation’s philosophical outlook on life.

It is evident from examining Camus’ speech in this format that Camus’ speech was compiled in this booklet long after the actual speech. Hence, this was not a mode Camus originally intended to be published in. This booklet serves as a source of history by commemorating an important milestone in the author’s life. Thus, it can be seen more as a historical source of record than a work Camus wanted to be read in the printed format.

Albert Camus emphasizes how he considers himself inseparable from his art but has never considered himself disconnected from rest of society as an artist. On the contrary, he is firm that his art ‘cannot be separated from my fellow men’ and allows him to live on ‘one level with’ everyone else by appealing to universal emotions through his portrayals of joys and sufferings of ordinary people.

Albert Camus considers himself to be part of a generation of turmoil who were ‘born at the beginning of the First World War’, who were ‘twenty when Hitler came to power’ and ‘confronted as a completion of their education with the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, the world of concentration camps, a Europe of torture and prisons’. As a result of living through these tremendously stressful times, Camus admits, many of this generation has ‘asserted their right to dishonor and have rushed into the nihilism’. Camus considers himself to be one of those who ‘have refused this nihilism’ and strives to create ‘an art of living in times of catastrophe’. deserves to be saluted and encouraged, particularly where it is sacrificing itself.

Thus, Camus finds a dual role of the artist in modern society – both to help create a source of meaning for society itself, by refusing nihilism, but also to celebrate ‘the beauty he cannot do without and the community he cannot tear himself away from.’ He does not believe in art ‘for art’s sake’, detached from the rest of society, instead, art must have a broader, critical role in society, and must be dedicated to those who ‘suffer’ history, resisting oppression, and intended to serve truth and liberty. His art honors the ‘silent men’ who ‘sustain the life made for them in the world only through memory of the return of brief and free happiness.’

Thus, Camus’ works tackle the questions as to what gives individuals a sense of purpose amidst times of despair. In the story ‘The Adulterous Woman’, written in 1957, Janine and her husband Marcel travel to a foreign land, presumably colonial North Africa, for Marcel’s business purposes. She realizes that she feels less and less emotionally attached to her marriage. She desperately tries to reconcile her thoughts, her desires and her past aspirations. In the final scene, she comprehends the vastness of the external world and tries to keep her emotions under control. Janine does not commit an actual act of adultery. Camus portrays her sympathetically as she tries to find purpose in her life, and the narrator of the story is not judgmental. The depiction of emotions is as it is, without any overt commentary praising condemning the motivations. This links back to Camus’ Nobel acceptance speech, where he says, “What writer would from now on in good conscience dare set himself up as a preacher of virtue?” Camus acknowledges how it is hard to find an objective meaning and purpose of life in the post-World War II society, and wonders if ‘this generation will ever be able to accomplish this immense task’ – yet he applauds every attempt to do so, even when the attempt is merely one woman’s efforts to reconcile her desires for external freedom and her attachments to her husband.

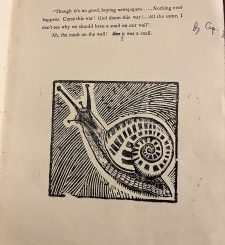

The disappointment Janine feels in her own life is mirrored by her disappointment during the trip. In the story, she saw that ‘the desert was not that at all, but merely stone, stone everywhere, in the sky full of nothing but stone-dust’. The visions of ‘the fort gazing over the vast horizon’, although seemingly promising novelty and freedom, remains elusive for Janine. The act of finding meaning amidst monotonousness and ennui is a challenge for Janine, and also a recurring theme in Camus’ works. Just as Camus talks about the role of art and creativity in trying to find meaning after the horrors of World War II in his speech, Camus celebrates the act of finding meaning in his literary works.

Camus, in his speech, says that art provides ‘a privileged image of our common joys and woes’. his portrayal of the intimate internal emotions of Janine makes the readers appreciate the common threads across humanity. He shows that overcoming one’s own discouragements and finding motivation for goals are struggles many human beings irrespective of race, gender or creed go through. Janine’s ‘adultery’ then, is only the act of ‘thinking beyond’ the societal structures that bound her and restricted her possibilities of thought. The attempt to find one’s purpose is adulterous against the status quo and the default societal norms. Here it is interesting to note that the initial temptation for Janine is a French soldier. Camus’ speech is firmly anti-war and pacifist – Camus talks about a ‘world threatened by nuclear destruction’ and the duty of his generation to act against the ‘instinct of death’. The acceptance of militarism as inevitable is precisely the ‘nihilism’ that Camus warns society against. Camus thinks that society needs an immense strength of character to create ‘an art of living in times of catastrophe’.

We must also keep in mind that a key postcolonial criticism of Camus has been his position towards French imperialism and his refusal to outright condemn the French colonial government. Writing within the context of Algeria’s colonial conflicts, Camus’ stories highlight the limits of his universalist ethics. Indeed, although the story ‘The Adulterous Woman’ poignantly portrays Janine’s yearnings for freedom, the lack of character development of the Arab people is quite stark. The native Algerians are almost like background props with no dialogue of their own – neither are their emotions, their motivations elaborated on. In the beginning of the story, we have ‘the bus was full of Arabs pretending to sleep, shrouded in their burnooses…their silence and impassivity began to weigh upon Janine’. The narrator describes how ‘they had ceased talking and were silently progressing in a sort of sleepless night’. Marcel says, quite dismissively, ‘“You may be sure he’s never seen a motor in his life”.’ We see that the Arabs are in subservient roles to Janine and Marcel – for example, ‘an elderly Arab wearing a military decoration on his tunic served them’, ‘Marcel urged the elderly Arab to hurry the coffee’ and ‘Marcel called a young Arab to help him carry the trunk’. Janine’s ‘gaze’ towards the Arab natives could even be accused of being orientalist.

Camus does mention that he considers the Nobel prize surpassing his own merits, and that he receives it as a ‘homage rendered to all those who, sharing in the same fight, have not received any privilege, but have on the contrary known misery and persecution.’ It seems ironic that, given Camus’ emphasis on literature serving a critical role in society, the story does not give any space to portray the perspective of the Arabs, who ‘have not received any privilege, but have on the contrary known misery and persecution’, who see foreigners from their colonizing country arrive for ‘business purposes’. One must applaud Camus’ attempts to portray the subaltern female voice, where he poignantly puts forward Janine’s anxieties on whether her husband loves her, and her mental trials to discern her true emotions towards her husband were. But one cannot help but notice Camus’ Eurocentric viewpoint of storytelling. Nevertheless, reading Camus’ Nobel acceptance speech enables us to appreciate the inner thoughts and motivations of one of the most influential French authors of the 20th century, and discern his messages for the audience, and how he wanted his work to be appreciated.

Recent Comments