The Materialism in Oscar Wilde’s Love by Aimi W.

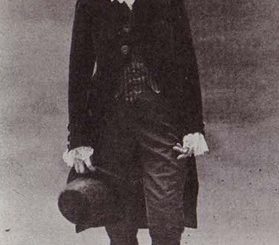

At first glance, “The Nightingale and the Rose” by Oscar Wilde seems to simply be a metaphor for the lack of acknowledgement of people’s– or in this case, a nightingale’s– sacrifices for love. Before I delved into his personal letters, I had expected dramatic descriptions of love and emotional pains similar to the ones in the story, especially since most of his letters are dated during the time he was recently convicted of homosexuality in England by the father of his ex-lover and was living in exile in France.

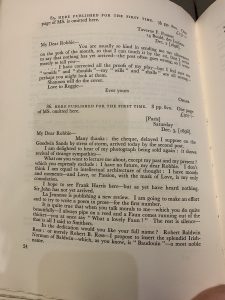

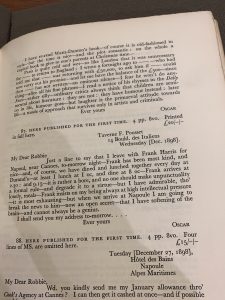

However, when I read through Wilde’s letters to his “dear Robbie,” I was struck by the strange blend of love and materialism that was consistent across most of his letters. Within each letter, he always establishes a close intimate, almost-romantic relationship with Robbie by addressing him as “My Dear Robbie.” Wilde switches between talking about his emotions and addressing Robbie in an intimate manner to requesting money. For example, in a letter dated December 3rd, 1898, he starts off talking about how a long-awaited “cheque” from Robbie finally arrived. Immediately, in the next paragraph, Wilde writes “I have no future, my dear Robbie… I have moods and moments- and Love, or Passion, with the mask of Love, as my only consolation.” He seems to be quite despondent. He is describing mood swings and a disenchantment with love by calling it “Passion, with the mask of Love.” I had expected this kind of emotional distress in Wilde’s letters.

Yet, in the next paragraph, he seems to turn off his emotions quite abruptly by switching his tone to a more academic one through discussing some literary works that he had written or read. In the last paragraph, he again brings up the money issue: “let me have the balance of the £500,” which is about $74,883 today. Instead of letting it end on such a cold note, he concludes with “Ever yours Oscar,” further establishing and reminding Robbie of their intimate relationship while requesting material goods. To me, he treats Robbie as both a lover, a close confidante, and a money-manager. After researching the “dear Robbie” in Wilde’s letters, Robbie turned out to be Robert Ross, and he was Wilde’s lover and editor. Wilde was not afraid of mixing his personal and business lives together. By repeatedly switching between emotions and materialism, Wilde interlaces the two concepts together: one does not really exist without the other.

Additionally, when I read through a few more of his letters, I found that the amount of money he requested is usually not for necessities but for luxuries. For example, he wrote about dining with Frank Harris at Durand’s and Marie’s, dining with Strong and other women, and living in a hotel that charged 100 francs a month. Wilde continued to live a social and relatively luxurious life. He certainly did not forgo any sort of self-indulgence.

After reading his letters, I re-read “The Nightingale and the Rose” and noticed similarities between the letter and the story. In the story, a Student falls in love with the daughter of the professor. The daughter asks the Student for a red rose at a time when red roses are nowhere to be found. The nightingale overhears and sacrifices herself to make a red rose for the Student. However, when the Student presents the rose to the daughter, she rejects it in favor of jewels. The Student returns to his study and throws the rose away, causing it to be trampled on by a cart. First and foremost, the Student’s ending actions reminded me of the actions of Wilde in the letter I was examining in the previous paragraph. Like Wilde, the Student switches from talk about love to academics and eschews love. Second, like the letters, the story juxtaposes love and materialism. The red rose, representing the Nightingale’s passion and love, was compared to the Professor’s daughter’s dress and the Chamberlain’s nephew’s jewels and silver buckles. The red rose ultimately “lost” to these symbols of luxury, and it was trampled on by a cart.

Because of the constant combination of love and money in the letters and the story, the motivation behind “The Nightingale and the Rose” becomes complex. Is “The Nightingale and the Rose” a self-critique or self-evaluation? Was Wilde critiquing society, not realizing his own hypocrisy? Or was he even critiquing anything? Is “The Nightingale and the Rose” simply a sad tale illustrating the unfortunate truth that people value money more than love? For me, I lean towards the last question. There does not seem to be any condemning tone in either the story and letter. They were delivered in an almost matter-of-fact tone that left the reader to interpret however they want to.

Recent Comments