“The Dead” and a Scrapbook on Joyce by Cathy C.

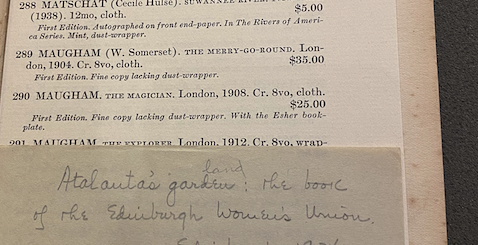

I examined a huge green scrapbook of clippings and articles about James Joyce. The scrapbook pages are not in perfect chronological order, skipping around from about 1920-1950, and contain items like portraits, literary reviews, and newspaper articles. The collection seemed almost obsessive, since all of these materials had been cut and pasted by hand into this giant hardcover book. The clippings and articles came mostly from American publications, and there were a lot of them, demonstrating how prevalent Joyce’s works were at the time. Perhaps the American clippings were all that the author of this scrapbook had access to, or it could be that the Joyce’s popularity amongst American publications was too intriguing; that it had something to do with his doggedly relatable portrayals of the human condition despite his past work, Dubliners, having to do strictly with Ireland. James Joyce might not have been loved by everyone, but his works were certainly widespread; one feels the anticipation of Ulysses that shows up throughout the scrapbook to be a compliment on how Joyce keeps his critics and fans alike captivated.

While combing through the scrapbook, I came across a March 1922 Vanity Fair article by Djuna Barnes called “A Portrait of the Man Who is, at Present, One of the More Significant Figures in Literature.” Barnes speaks of Joyce’s appearance and states that he must have been “a very tender singer and – because no voice can hold out over the brutalities of life without breaking – he turned to quill and paper” (Barnes). The idea of Joyce as singer took me back to the short story “The Dead,” when the singer Bartell D’Arcy sings The Lass of Aughrim and begins the final conflict of the narrative. “The Dead” is a tale about an upper-middle class dinner party and follows the protagonist Gabriel as he navigates this particular social setting. In both this article and “The Dead,” music is treated as a language of emotions. I agree with Barnes – the last line of “The Dead” is particularly sonorous and most evokes the image of Joyce as singer: “His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead” (Joyce 412). The alliteration, sibilance, and the syntactical breaks in the last half of the sentence contribute to the musical feel of Joyce’s beautiful writing.

Barnes also describes Joyce as having “…the sadness of a man who has procured some medieval permission to sorrow out of time and in no place: the weariness of one self-subjected to the creation of an overabundance in the limited” (Barnes). Barnes implies that Joyce embodies a blurring of the lines of time and space, which parallels how Gretta, Gabriel’s wife, grieves for her old lost lover in a way that transcends time and how Gabriel’s resulting somber meditation on the snow falling through the universe transcends space. Since it was hearing the song that caused Gretta to grieve, music acted as the vehicle that allowed Gretta’s emotions to become timeless and universal. Viewing the final scene of “The Dead” through the lens of blurred boundaries caused me to read the sense of loss as being a communal, mystical pain that all humans, dead and alive, have felt or will feel; pain that cannot be constrained through boundaries and as such is a necessary part of the universal human experience.

Recent Comments