by Alyssa Granacki

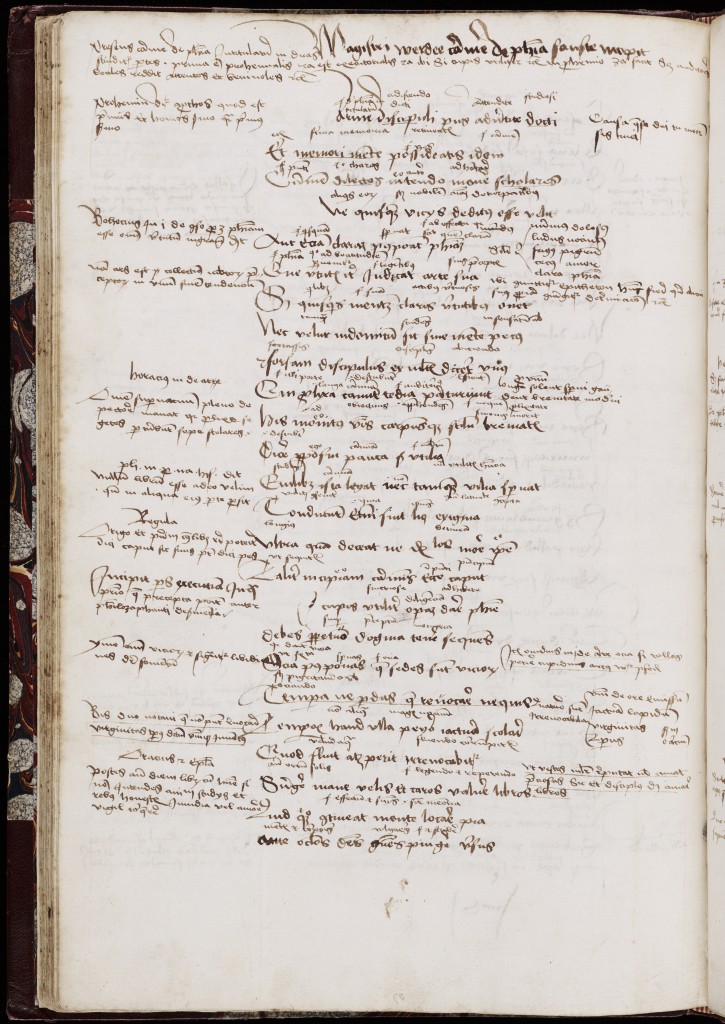

Dante mentions Ovid in Chapter 25 of the Vita Nuova when he interrupts the narrative to address his use of personified Love: “At this point a question might be raised by someone… and what he might question is the fact that I speak of Love as if it were a thing in itself” [Potrebbe qui dubitare persona… che io dico d’Amore come se fosse una cosa per sè]. Along with Virgil, Lucan, Horace, and Homer, Dante cites Ovid as an example of a poet who “makes Love speak as if it were human” [Per Ovidio parla Amore, sì come fosse persona umana]. Yet instead of citing Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, an instructional guide in the art of love, his Amores, a collection of erotic elegies, or even the Metamorphoses, Dante quotes from Ovid’s Remedia Amoris, or Remedies for Love. Some scholars argue that by choosing the Remedia, Dante rejects “the pornographic Ovid,” and distinguishes his love for Beatrice and asserts his status as a love poet (Ginsberg 146). Nevertheless, the Remedia offers some erotic advice of its own, reminiscent of the sensual poetry of the Amores and the seduction techniques of Ars. We can only speculate why Dante chose this work rather than another, but perhaps the insistence on abandoning love in the Remedia contrasts with Dante’s dedication to Beatrice. Ovid’s poems undoubtedly influenced Dante, as this intertextual moment suggests. Yet the form in which Dante read them may have been equally as important. Michelangelo Picone argues that Dante’s use of prosimetrum, the interspersing of prose and poetry, in the Vita Nuova was inspired by his reading of Ovid’s works. In a medieval manuscript, the Remedia, or a similar poetic text, would be displayed in the middle of the page, encircled by the prose of commentators. Prose glosses acted as a vehicle for interpreters, often Christian, to explain the meaning of a Latin poem. Although the manuscript shown here dates several centuries after Dante, it still follows the same format as earlier manuscripts. The Latin poem is in the center of the page in a slightly larger hand than the interlinear and marginal commentaries. Interlinear commentaries were more likely to address grammatical or philological issues, while longer glosses in the margin tended to be allegorical or literary comments.

Beinecke MS 174. Manuscript on paper, 320 x 212 (280 x 108) mm., late 15th century. Ovid, Remedia amoris, followed by two series of short poems by Pseudo-Vergil and Johannes Fabri de Werdea. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The incipit of the Vita Nuova in an early fourteenth century manuscript.

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, ms. Chigiano L VIII 305, c. 7r.

Dante’s prose in the Vita Nuova performs a similar function to the allegorical glosses we find in Ovidian manuscripts. After presenting a love poem, Dante offers an interpretation in prose, often adding a religious element to the poem. The first poem, For every gentle heart and captive soul [A ciascun alma presa e gentil core], circulated before the publication of the Vita Nuova, and contains no explicit religious language. In the prose, however, Dante suggests that at the end of his vision, Beatrice ascends to heaven. His use of Latin in the prose imbues the work with a scholarly and religious tone we do not find in the original love poem.

For an interactive look at intertextuality in Dante and Ovid, see the Digital Dante project.

Selected Bibliography

Black, Robert. “Ovid in Medieval Italy,” in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. Clark, Coulson, and McKinley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Curtius, Robert Ernst. European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. Translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: Bollingen Foundation; Pantheon Books, 1953.

Ginsberg, Warren. “Dante’s Ovids,” in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. Clark, Coulson, and McKinley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Kenney, E.J. “The Manuscript Tradition of Ovid’s Amores, Ars Amatoria, and Remedia Amoris.” The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 12, no. 1 (1962): 1-31.

Marchesi, Simone. “Distilling Ovid: Dante’s Exile and Some Metamorphic Nomenclature in Hell,” in Writers Reading Writers: Intertextual Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007.

Paratore, Ettore. “Ovidio Nasone, Publio” in Enciclopedia Dantesca, 1970. (http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/publio-ovidio-nasone_(Enciclopedia-Dantesca)/)

Picone, Michelangelo. “Dante and the Classics” in Dante: Contemporary Perspectives. Edited by Amilcare A. Iannuci. Tornoto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Sowell, Madison U., ed. Dante and Ovid: Essays in Intertextuality. Binghamton, New York: Center for Medieval and Early Resnaissance Studies, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1991.