by Alyssa Granacki

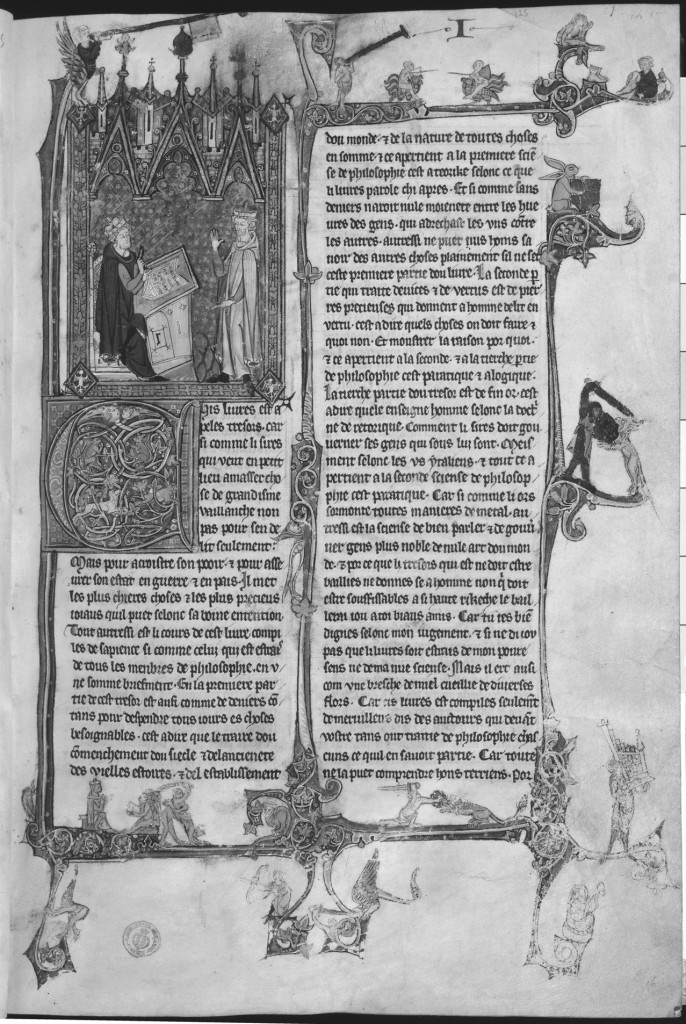

Black and white facsimile of Ashburnham 125 c.016r. Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana.

The parallels between Dante’s Comedy and the Tesoretto are quite obvious, but Dante also would have been familiar with Brunetto Latini’s Trésor. Latini wrote Li Livres dou Trésor in the mid 1260s in French, participating in another medieval phenomenon: producing encyclopedic works. The Trésor circulated widely in Italy, and Latini even later repurposed some of its content in the Tesoretto. The work was translated into the Italian vernacular as early as the fourteenth century, but Dante would have known the original in French, as pictured here in the manuscript Ashburnham 125, housed at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

The Trésor consists of three books, covering a variety of topics, including history, religion, the natural world, philosophy, ethics, and politics. As a repository of the culture that surrounded Dante, it offers unique insight into his intellectual formation. The deluxe Trésor manuscripts dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, pictured below, also speak to the status of Latini’s text and its importance in the medieval world.

Bibliothèque de Genève, Ms. fr. 160. Brunetto-Latini Trésor. Available via e-codices.

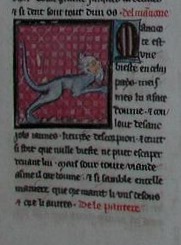

Bestiary in Book of the Treasure. National Library of St. Petersburg, Russia. Fr. F. v. III, 4. Facsimile by M. Moleiro.

Manticore from the Bestiary. Book of Treasures, National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg. Facsimile by M. Moleiro.

In his discussion of the natural world, Latini provides a spectacular bestiary with descriptions of seventy different animals (I.130-199), as seen in the manuscript above. Of particular interest is Latini’s description of the Manticore (I.192) – a beast with a man’s face, a lion’s body, and the tale of a Scorpion, which echoes Dante’s own description of the beast Geryon in Inferno (17.1-27): “The face he wore was that of a just man… and all his trunk, the body of a serpent… his tail… which had a tip just like a scorpion’s” [La faccia sua era faccia d’ uom giusto…e d’un serpente tutto l’altro fusto… tutta sua coda… ch’ a guisa di scorpion la punta armava].

Latini’s encyclopedic collection probably influenced Dante in numerous ways. Several figures, historical and literary, appear in both Brunetto’s and Dante’s works. For example, Latini offers chapters on Aeneas (I.33-34) and Frederick II (I.95-98) whom Dante references in Inferno 1 and Inferno 10, respectively. In book two, Latini translates the Ethics of Aristotle into French, and it is these Ethics that Virgil cites in the Comedy (Inf 11.79-80) in order to explain the organization of Hell to Dante. A rich discussion of vices and virtues, including capital sins, follows Latini’s translation of Aristotle’s Ethics, and Dante’s own judgment of such vices and virtues will be imagined in the Comedy.

The third and final book contains a robust discussion of politics. This would also have been a formative text for Dante, who, like Latini, was deeply involved in the Florentine politics and supported the Guelphs. Latini even warns Dante in the Inferno (15.61-78) about the discord between the Ghibellines and the Guelphs, which resulted in Latini’s exile and would ultimately be the cause of Dante’s as well.

Selected Bibliography

Baldwin, Spurgeon and Paul Barrette. Introduction to The Book of the Treasure (Li Livres dou Tresor) by Brunetto Latini, translated by Spurgeon Baldwin and Paul Barrette. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993.

Giola, Marco. La tradizione dei volgarizzamenti toscani del <<Tresor>> di Brunetto Latini. Verona: QuiEdit di S.D.S. s.n.c, 2010.

Holloway, Julia Bolton. Introduction to Il Tesoretto by Brunetto Latini, edited and translated by Julia Bolton Holloway. New York: Grand Publishing, Inc., 1981.

Inglese, Giorgio. “Latini, Brunetto.” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 64, 2005. (http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/brunetto-latini_(Dizionario-Biografico)/).

Kay, Richard. “The Sin(s) of Brunetto Latini.” Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society, no. 112 (1994):19-31.

Mazzoni, Francesco. “Latini, Brunetto.” Enciclopedia Dantesca, 1970. Available via Treccani: http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/brunetto-latini_(Enciclopedia-Dantesca)/

Roux, Brigitte. Mondes en miniatures: l’iconographie du Livre du trésor de Brunetto Latini. Genéve: Libraire Droz S.A., 2009.