by Alyssa Granacki

Brunetto Latini appears in Inferno 15 among the sodomites in the seventh circle of Hell. Readers often notice the tenderness Dante exhibits toward his mentor and the affection Brunetto expresses for Dante. Brunetto uses “son” [figliuol] as a term of endearment during their encounter (Inf 15.31, 37), and Dante describes walking beside Brunetto “with head bent low /as does a man who goes in reverence” [ma ‘l capo chino/ tenea com’ uom che reverente vada] (Inf 15.44-45). While Dante uses the formal second person pronoun, voi, to address Brunetto, he speaks to Dante using the informal tu, signifying Dante’s deference to his mentor. At the end of the canto Brunetto pleads, “Let my Tesoro, in which I still live, /be precious to you; and I ask no more” [Sieti raccomandato il mio Tesoro nel qual io vivo ancora, /e più non cheggio] (Inf 15.118-120). This could be a reference to Latini’s encyclopedic work in French, Li Livres dou Trésor, but could also refer to his poem, the Tesoretto.

Dante and Brunetto Latini. Fresco of San Bargello, attributed to Giotto.

The Tesoretto is often recognized as a precursor to Dante’s Divine Comedy. The poem follows in the medieval tradition of philosophical poetry in which a narrator recounts a dream-like vision. Latini’s poem, like Dante’s, even begins with the author/protagonist lost in dark wood: “And I, in such anguish, /thinking with head downcast, /lost the great highway, /and took the crossroad /through a strange wood” [E io in tal corrocto/pensando a cap chino/perdei il gran cammino/e tenni a la traversa/d’una selva diversa] (184-189). Latini carefully inserts himself into a poetic tradition within the course of his poem, just as Dante does in Inferno 4. Dante certainly would have known this work and his self-presentation in the Comedy clearly draws inspiration from Latini’s. Some even argue that he could have been the scribe of a suriving manuscript of the Tesoretto, Strozziano 146.

In the Tesoretto, Brunetto’s teacher is the poet Ovid. Brunetto asks Ovid to instruct him in matters of love, personified by Cupid: “And [I] asked the man himself/ that he should openly /tell me the workings/ both the good and the evil, /of this child with wings” [E domandai lui stesso/ch’elli apertamente/mi dica il convenente/e lo bene e lo male/del fante e dell’ale] (2364-2369). This relationship is illustrated in Strozziano 146, which shows Ovid at an imposing writing desk and Brunetto standing before him as his student. Ovid appears older and more commanding than Brunetto, and his place at the desk further emphasizes his position of power. The image is also an inversion of the opening illustration of the manuscript, which depicts Latini occupying the place at the writing desk, instructing his own reader. In fact, after his encounter with Ovid, Latini declares: “But Ovid through artistry/ gave me the mastery,/ so that I found the way /from which I had strayed.” [Ma ovidio per arte/mi diede maestria/si ch’io trovai la via/ ond’io mi traffugai] (2390-2394). Although Brunetto recognizes his predecessor, he ultimately asserts his own authority as a poet.

Brunetto Latini before Ovid. Strozziano 146, Fol. 21v. © Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana. 13th century.

Dante employs a similar method in Inferno 4 when he encounters the great poets in Limbo. Among Virgil, Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan, Dante claims his place: “I was sixth among such intellects” [sì ch’io fui sesto tra cotanto senno] (IV.102). Dante also recognizes his debt to Brunetto as his teacher: “your dear, your kind paternal image when, in the world above, from time to time, you taught me how man makes himself eternal” [la cara e buona imagine paterna di voi quando nel mondo ad ora ad ora m’insegnavate come l’uom s’etterna] (Inf. 15.83-85). However, the relationship in the Comedy that most reflects this link to the poetic tradition is that of Dante and Virgil. In Inferno, Dante recognizes Virgil as his “author and master” [Tu se’ lo mio maestro e ‘l mio autore] (Inf 1.85). Virgil serves as Dante’s guide throughout the Inferno and Purgatory but eventually Dante leaves him behind, as he ascends when Virgil cannot.

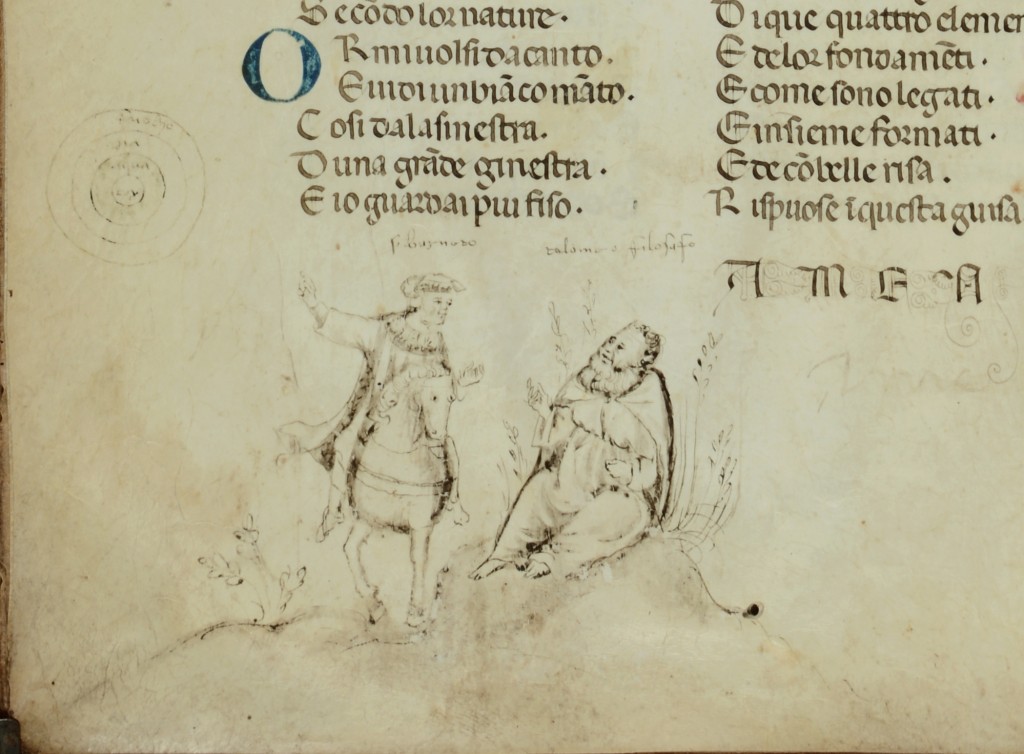

Latini’s text points us to another source of Dante’s as well. On the final page of Strozziano 146, an illustration depicts Brunetto Latini upon a horse, pointing towards a model of the earth, which is surrounded by the sea, then air, then fire. To Brunetto’s left is Ptolemy, identified as tolomeo filosofo. Dante mentions Ptolemy in his philosophical treatise, the Convivio (Book II, Ch. 14): “In the Old Translation he [Aristotle] says that the Galaxy is nothing but a multitude of fixed stars in that region… Avicenna and Ptolemy seem to share this opinion with Aristotle.” Echoes of the Ptolemaic conception of the universe (as well as the Platonic) appear throughout the Comedy, and the concentric circles in this drawing reflect the organization of Dante’s own Paradise.

Brunetto and Ptolomey. Strozziano 146. © Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana. 13th century.

Selected Bibliography

Baldwin, Spurgeon and Paul Barrette. Introduction to The Book of the Treasure (Li Livres dou Tresor) by Brunetto Latini, translated by Spurgeon Baldwin and Paul Barrette. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993.

Giola, Marco. La tradizione dei volgarizzamenti toscani del <<Tresor>> di Brunetto Latini. Verona: QuiEdit di S.D.S. s.n.c, 2010.

Holloway, Julia Bolton. Introduction to Il Tesoretto by Brunetto Latini, edited and translated by Julia Bolton Holloway. New York: Grand Publishing, Inc., 1981.

Inglese, Giorgio. “Latini, Brunetto.” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 64, 2005. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/brunetto-latini_(Dizionario-Biografico)/.

Kay, Richard. “The Sin(s) of Brunetto Latini.” Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society, no. 112 (1994):19-31.

Mazzoni, Francesco. “Latini, Brunetto.” Enciclopedia Dantesca, 1970. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/brunetto-latini_(Enciclopedia-Dantesca)/.

Roux, Brigitte. Mondes en miniatures: l’iconographie du Livre du trésor de Brunetto Latini. Genéve: Libraire Droz S.A., 2009.